Quintinshill rail disaster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Quintinshill rail disaster |

|

|---|---|

A burning carriage in the aftermath of the collisions

|

|

| Details | |

| Date | 22 May 1915 6:49 am |

| Location | Quintinshill, Dumfriesshire, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°00′53″N 3°03′54″W / 55.0146°N 3.0649°W |

| Country | Scotland |

| Line | Caledonian Main Line part of the West Coast Main Line |

| Operator | Caledonian Railway |

| Incident type | Double collision, fire |

| Cause | Signalling error |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 5 |

| Deaths | 226 |

| Injured | 246 |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The Quintinshill rail disaster was a terrible train crash that happened on 22 May 1915. It took place near a signal box called Quintinshill, close to Gretna Green in Scotland. This accident involved multiple trains and caused the deaths of over 200 people. It is still known as the worst train disaster in British history.

The crash happened because of mistakes made by the signalmen. A southbound troop train crashed into a local passenger train that was stopped on the wrong track. Moments later, another express train crashed into the wreckage. A huge fire then broke out because the troop train's old wooden carriages used gas for lighting. This made the disaster much worse. Many of the people who died were soldiers from the Royal Scots regiment. They were on their way to fight in World War I.

Contents

How the Trains Were Controlled

The Quintinshill signal box was a small building that controlled train movements. It was located on the main railway line between Glasgow and Carlisle. This line was part of the important West Coast Main Line.

The signal box had control over two "passing loops." These are extra tracks where trains can wait to let other trains go by. One loop was for trains heading towards Carlisle (called "Up" trains). The other loop was for trains heading towards Glasgow (called "Down" trains).

The signal box was in a quiet, rural area. The closest town was Gretna, about 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles) away. The person in charge of the signal box was the stationmaster at Gretna.

Signal boxes were usually staffed by one signalman per shift. On the day of the accident, George Meakin was finishing his night shift. James Tinsley was starting his early morning shift.

Normally, two fast overnight trains from London would pass through Quintinshill in the morning. These were followed by a local passenger train that stopped at all stations. If the fast trains were running late, the local train would sometimes be moved onto a side track. This allowed the faster trains to pass.

One place where the local train could be moved was Quintinshill. If the "Down" (northbound) passing loop was busy, the local train would be moved onto the "Up" (southbound) main line. This was allowed, but it meant the train was on a track usually used by trains going the other way. Special safety steps had to be followed.

The Accident Happens

Train Movements Before the Crash

On the morning of 22 May, both fast northbound trains were running late. The local passenger train needed to be moved out of their way at Quintinshill. However, the "Down" passing loop was already full with a goods train.

So, the night signalman, George Meakin, decided to move the local passenger train onto the "Up" main line. At the same time, a southbound train carrying empty coal wagons was waiting nearby. Meakin allowed this coal train to move into the "Up" loop.

James Tinsley, the signalman for the early morning shift, arrived late. He got to the signal box around 6:30 AM. He had actually traveled on the local passenger train that was now stopped on the "Up" main line.

After Tinsley arrived, the signalmen should have sent a special signal to the next signal box (Kirkpatrick). This signal, called "blocking back," would tell Kirkpatrick that a train was stopped on the "Up" main line at Quintinshill. This signal was never sent.

Meakin stayed in the signal box after his shift, reading a newspaper. The guards from the freight trains were also in the box, chatting about war news. This meant there were too many people in the small signal box, which could be distracting.

A railway rule, called Rule 55, said that if a train stopped on the main line for more than three minutes, a crew member had to go to the signal box. They had to remind the signalman about the train and make sure safety measures were in place. The local train's fireman, George Hutchinson, went to the box. But he just signed a book and left without properly checking that the signalman had remembered his train.

The Collisions

At 6:42 AM, the signal box at Kirkpatrick offered the southbound troop train to Quintinshill. Signalman Tinsley immediately accepted it. He forgot completely about the local passenger train that was still sitting on the "Up" main line, right in front of him.

Tinsley then pulled the signal lever to allow the troop train to come through.

The troop train crashed head-on into the stopped local train at 6:49 AM. Just over a minute later, the second northbound express train also crashed into the wreckage. The crash also involved the goods train in the "Down" loop and the empty coal train in the "Up" loop.

At 6:53 AM, Tinsley finally sent an "Obstruction Danger" signal to other signal boxes. This stopped all other trains and alerted everyone to the terrible disaster.

The Fire

Many people on the troop train died from the collisions. But the disaster became much worse because of a huge fire. During wartime, there weren't enough modern train carriages. So, the railway company had to use older, wooden carriages for the troop train. These carriages were lit by gas.

The gas was stored in tanks under the train. When the trains crashed, these tanks broke open. The gas escaped and was set on fire by the hot engines. The gas tanks were full, and there wasn't much water available. This meant the fire burned intensely until the next morning. Firefighters from Carlisle tried their best to put it out.

The troop train had 21 carriages. All but the last six were destroyed by the fire. The fire also damaged four carriages from the express train and some goods wagons. The heat was so strong that all the coal in the train engines' storage areas burned up.

Rescue Efforts

Among the first people to arrive were Mr. and Mrs. Dunbar, who looked after a nearby famous landmark. Mrs. Dunbar called doctors in Carlisle for help. Mr. Dunbar spent the day helping with the rescue.

It was a very difficult scene. Some soldiers were trapped in the burning wreckage. There were reports that some officers made very hard decisions to help soldiers who were suffering greatly. This was a desperate situation, and people did what they felt was necessary to ease pain.

After the Disaster

By 24 May, newspapers were reporting that this was the deadliest train accident in the United Kingdom. At first, it was thought that 158 people had died. The bodies were first placed in a field and covered with sheets. Later, they were moved to a nearby farm or the Gretna Green Village Hall.

The King of England, George V, sent a message to the railway company. He expressed his sadness and asked to be kept updated on the injured.

The railway line at Quintinshill was reopened on 25 May. This was even though not all the wreckage had been cleared away.

People Affected

Most of the people who died were soldiers from the Royal Scots. The exact number of deaths was hard to figure out. This was because the list of soldiers was destroyed in the fire. The official report estimated that 215 soldiers died, and 191 were injured. Out of 500 soldiers on the troop train, only 58 men and seven officers were found alive later that day.

In total, about 226 people died, and 246 were injured. The driver and fireman of the troop train also died in the first crash.

The other trains had fewer casualties. On the local train, two passengers died. On the express train, seven passengers died, and 51 passengers and three railway workers were seriously hurt.

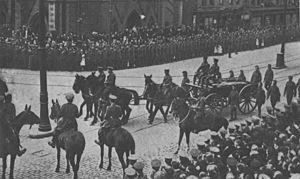

Funerals

Some bodies were never found because they were completely burned in the fire. The bodies of the Royal Scots soldiers were returned to Leith on 24 May. They were buried together in a large grave at Rosebank Cemetery in Edinburgh. The coffins were placed three deep, and those on top were covered with the Union Flag.

The public was not allowed into the cemetery. However, 50 injured soldiers from a nearby hospital were allowed to attend. The ceremony lasted three hours. A memorial for the dead soldiers was put up in Rosebank Cemetery in 1916.

Out of the soldiers, 83 bodies were identified. 82 bodies were found but could not be recognized. 50 soldiers were completely missing. The soldiers were buried with full military honors.

Among the coffins were four unidentified bodies that seemed to be children. One coffin was simply marked "little girl, unrecognisable." Another said "three trunks, probably children." Since no children were reported missing, the railway company moved the bodies to Glasgow. No one ever claimed them, so they were buried in Glasgow's Western Necropolis on 26 May.

Survivors

The soldiers who survived were taken to Carlisle on the evening of 22 May. The next morning, they went to Liverpool by train. There, they had medical checks. Most of the soldiers and one officer were found to be too injured to go overseas. They were sent back to Edinburgh. Only Lieutenant Colonel W. Carmichael Peebles and five other officers were well enough to sail for duty overseas.

The Trains Involved

Four steam locomotives were pulling the three passenger trains in the crashes. The express train had two engines pulling it. All these engines were built for the Caledonian Railway.

The two engines that crashed head-on in the first impact were so badly damaged they had to be scrapped. These were No. 907 from the local train and No. 121 from the troop train.

The two engines from the express train, No. 140 and No. 48, were later repaired. They were able to return to service.

Investigations and What Went Wrong

Rules That Were Broken

The accident happened because many railway safety rules were not followed. These broken rules were the main reason the signalmen were later charged. Eight different rule breaks by the signalmen were found.

Shift Change Problems

The signalmen had a bad habit of changing shifts late. The morning signalman would arrive around 6:30 AM instead of 6:00 AM. This allowed the day shift signalman, James Tinsley, to ride the local train to work when it was shunted at Quintinshill.

To hide this from their bosses, the night signalman would write down train movements on a piece of paper after 6:00 AM. When the day signalman arrived, he would copy these notes into the official record book. This made it look like the shift change happened on time. Changing shifts is a very important time for safety. The new signalman must know exactly where all trains are. This messy handover likely distracted Tinsley.

Missing Safety Signals

After the empty coal train stopped in the "Up" loop, two very important safety steps were missed.

First, after telling the next signal box (Kirkpatrick) that the coal train was clear, the Quintinshill signalman should have sent a "blocking back" signal. This signal would tell Kirkpatrick that another train (the local passenger train) was stopped on the "Up" main line. If Kirkpatrick had received this signal, they would not have been allowed to send another "Up" train (like the troop train) to Quintinshill. But the "blocking back" signal was never sent. Both signalmen later blamed each other for not sending it.

Second, the signalman at Quintinshill should have put a special "lever collar" on the signal lever. This is a physical reminder not to clear the signals for that line. Neither signalman did this. Tinsley also failed to check for a collar when he took over. Both signalmen admitted they didn't use these collars regularly.

Rule 55 Not Followed

Another important safety rule, Rule 55, was also not followed properly. This rule says that if a train stops on the main line for more than three minutes, a crew member must go to the signal box. They need to remind the signalman about the train and make sure all safety steps are in place. They also have to sign the train record book.

The local train had been stopped for more than three minutes. So, its fireman, George Hutchinson, went to the signal box. But he just signed the book without reminding the signalman about his train. He also didn't check for the lever collar.

Too Many People in the Signal Box

Railway workers were allowed to visit the signal box for their duties. But they were not allowed to stay longer than needed. This was to prevent distracting the signalman. However, signal boxes were warm and comfortable. So, visitors sometimes stayed too long.

When Tinsley arrived, the guard of a goods train was leaving after being there for about ten minutes. The guard of the empty coal train arrived at the same time and was still in the box when the first crash happened. Also, after his shift, signalman Meakin stayed in the box reading the newspaper. All these extra people likely distracted Tinsley from his important job.

Forgetting the Train

Because the "blocking back" signal wasn't sent, the Kirkpatrick signalman was able to offer the "Up" troop train to Quintinshill. But the local train was still on the "Up" main line. This meant Tinsley should not have accepted the troop train.

However, Tinsley forgot about the local passenger train. Even though he had just ridden on it minutes earlier, and it was right in front of the signal box, he forgot it was there. So, he accepted the troop train and pulled the signals to let it through.

Official Investigations

The first official investigation started on 25 May 1915. It was led by Lieutenant Colonel E. Druitt. He interviewed witnesses, including Meakin and Tinsley. Both signalmen were honest about their mistakes and not following the rules. Druitt's report blamed Meakin and Tinsley directly.

He also criticized fireman Hutchinson for not following Rule 55 properly. He also felt the stationmaster at Gretna should have known about the signalmen's bad habits.

Druitt believed that even if the trains had been lit by electricity, a fire still would have happened. This was because the goods train's wagons also caught fire. He also noted that if Quintinshill had modern safety systems (called "track circuits"), the accident would have been prevented. These systems would have stopped Tinsley from pulling the wrong signal levers.

The Trial

The trial of Tinsley, Meakin, and Hutchinson began on 24 September 1915 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were charged with "culpable homicide," which is similar to manslaughter. All three said they were not guilty.

The trial lasted a day and a half. The judge decided that fireman Hutchinson was not guilty. He had not done enough to prevent the crash, but his actions were not seen as criminal.

The jury found Tinsley and Meakin guilty. The judge sentenced Tinsley to three years in prison and Meakin to eighteen months.

After Prison

Meakin and Tinsley were released from prison on 15 December 1916. Tinsley went back to work for the Caledonian Railway as a lampman. He died in 1967. Meakin also returned to the railway as a goods train guard. Later, he became a coal merchant, working from Quintinshill, right next to where the crash happened. He died in 1953.

Memorials

There are several memorials to remember the Quintinshill disaster. One is at Rosebank Cemetery in Edinburgh, where many of the soldiers are buried. There is also a plaque at Larbert railway station, where the soldiers began their journey.

Two memorials have been put up by the Western Front Association near the crash site. One was placed in 1995, and another at Blacksyke Bridge in 2010. A memorial for the unknown children was put up in Glasgow in 2011.

Every year, remembrance services are held at Rosebank Cemetery. Important people, like the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, attend these services. For the 100th anniversary in 2015, the First Minister of Scotland and the Princess Royal attended services at Gretna and Rosebank Cemetery.

In 2017, a new housing area in Leith was given street names like Quintinshill Place and Gretna Place. These names remember the disaster.

Images for kids

See Also

- 1915 in rail transport

- List of rail accidents in the United Kingdom

- List of United Kingdom disasters by death toll

- List of transportation fires