Rappahannock Industrial Academy facts for kids

The Rappahannock Industrial Academy was a special school for African American children. It was open from 1902 to 1948 near Dunnsville in Essex County, Virginia. This school helped many students get a good education during a time when it was hard for African American children to go to high school.

Why the School Was Needed

After the Civil War ended and the Reconstruction period followed, Virginia made new rules for public education. However, the education available for African American students often stopped after the seventh grade. This meant many young people could not continue their studies.

In 1897, a group of churches called the Southside Rappahannock Baptist Association decided to do something about this. They wanted to create a school that would offer Christian education and help students build strong character. They knew about another school, the Manassas Industrial Academy, but it was too far away for most students in the Middle Peninsula area.

Building the Academy

By 1900, the group had raised enough money to buy a 159-acre farm for $1,200. Some of the money came from the Women's Baptist District Missionary Convention. They used part of the land to create a home for older people.

The school started in January 1902, using the farmhouse that was already there. The next year, they built a three-story dormitory for 45 girls and two teachers. This new building also had a dining hall, a chapel, and offices. Soon after, another building was added for 30 male students. It also had two teachers, three classrooms, a library, and a science lab. These buildings were named after two of the founding pastors, Reverend C. R. Towles and Dr. R. E. Berkley. In 1927, the school bought an additional 129 acres of land.

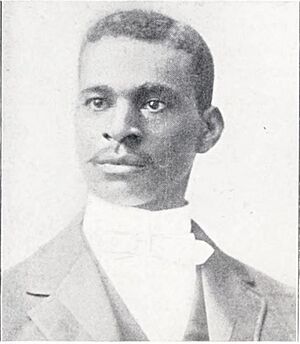

Leading the School

In 1903, Professor W. Edward Robinson became the school's principal. He was from Middlesex County and had studied at Howard University. He led the academy for 29 years, until he retired in 1933. His daughter, Edwardine Robinson, also went to the academy. She later became a teacher there after studying at Hartshorn Memorial College and Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia.

Even though it was called an "industrial academy," the school offered a strong college-prep program. Students learned subjects like algebra, geometry, Latin, English, and history. Each day started with a devotional assembly. Classes ran from 9 AM to 3 PM. After classes, students could study or join fun activities like sports, debates, and choir.

The course of study at first lasted two years, then it grew to three years. In 1934, the state officially recognized the school's program. From 1902 to 1948, the school's total cost to run was $107,000. Students paid about half of this amount through tuition and fees. The rest came from the Southside Rappahannock Baptist Association and from things the school produced.

The School's Legacy

The Rappahannock Industrial Academy closed in 1948. This happened after a lawyer named Oliver Hill won a court case in Virginia. The court decided that all students, no matter their race, must get free transportation to high schools. This meant more African American students could attend public high schools like Essex High School in Tappahannock, Virginia, which later received the Academy's records.

In 1992, former students of the academy raised money to put up a granite historical marker. It stands near the two remaining gateposts of the old school. The alumni association also gives out one scholarship each year to a student from each of the three original counties. This helps honor their old school and its important history.

A notable person who attended the school was civic activist Pauline C. Morton.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |