Golden-rumped sengi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Golden-rumped sengi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Rhynchocyon

|

| Species: |

chrysopygus

|

|

|

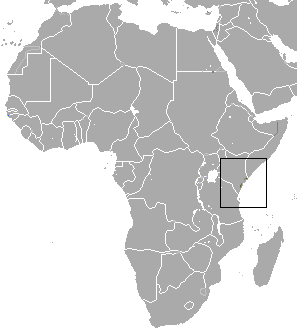

| Range | |

The golden-rumped sengi (Rhynchocyon chrysopygus) is a unique small mammal from Africa. It's one of the biggest members of the elephant shrew family. Its close relative is the grey-faced sengi. Sadly, this animal is currently listed as endangered.

Contents

About the Golden-Rumped Sengi

The golden-rumped sengi lives in the northern coastal areas of Kenya. You can find them in places like Arabuko Sokoke National Park near Mombasa. Their name comes from the bright golden fur on their back end. This golden color stands out against their dark reddish-brown body. They also have a grizzled gold forehead.

These sengis have long, strong back legs. Their front legs are shorter and not as developed. Like other elephant shrews, they have a long, flexible snout. This special nose is how their group got its name. Their tail is mostly black. But the last part of the tail is white with a black tip. Young sengis sometimes have faint patterns on their fur. These patterns are like the ones seen on other giant sengis, such as the checkered elephant shrew.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Golden-rumped sengis are monogamous. This means they stay with one partner. Both males and females protect their home areas. They mate all year long. Females usually give birth to one baby at a time. This happens about every 42 days.

Newborn sengis are ready to leave their mother's den after two weeks. They become fully independent about five days after leaving the nest. The male sengi does not help care for the babies.

Where They Live and What They Do

The golden-rumped sengi is active during the day. They live in thick forests with lots of plants. They avoid open areas to stay safe from predators. These sengis build up to six nests at a time. They switch nests every night. This helps them confuse predators and avoid being found.

They live in coastal areas. You can find them in moist, dense forests. They also live in lowland forests where some trees lose their leaves. Male sengis have slightly larger home areas than females. They are also more likely to go into neighboring territories. This makes them more likely to run into predators.

Diet and Behavior

Golden-rumped sengis eat small creatures without backbones. Their diet includes earthworms, millipedes, insects, and spiders. They spend most of their day (about 80%) searching through fallen leaves. They look for grasshoppers, beetles, spiders, and other small invertebrates.

These animals have clever ways to avoid predators. Their main enemies are snakes, like black mambas and cobras. They also watch out for the southern banded snake-eagle. The sengi is very fast. It can run up to 25 km/h (16 mph)! If a predator is too close, the sengi will get ready to defend itself. It will try to escape using its speed and quick movements.

If a predator is further away, the sengi will make noise. It slaps the leaf litter to let the predator know it has been seen. This often makes the predator leave. If there is a chase, the sengi's bright golden fur can help. The flash of gold often makes the predator focus on the sengi's back end. This part has thicker skin. This "dermal shield" is about three times thicker than the skin on its back. This can give the sengi a chance to get away. Males have an even more protected rump than females.

Each sengi keeps several nests. This makes it harder for predators to find them. They don't leave a clear trail or pattern.

Threats and Protecting Them

The golden-rumped sengi is an endangered species. This is mainly because their forest homes are broken up. Human activities also cause problems. Their largest group lives in the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest in Kenya.

Sengis can get caught in traps. However, people don't usually hunt them for food because they don't taste good. In the early 1990s, about 3,000 sengis were caught by trappers each year. Forest patrols have helped reduce trapping since then. But some areas are not patrolled, and trapping still happens there.

The Arabuko-Sokoke forest and other Kenyan forests where sengis live are protected as National Monuments. This stops new buildings from being built. However, it doesn't always provide specific protection for the sengis or other wildlife. Because their populations are small, their numbers are expected to keep going down. This is due to random events and more human disturbances.