Riddles (Finnic) facts for kids

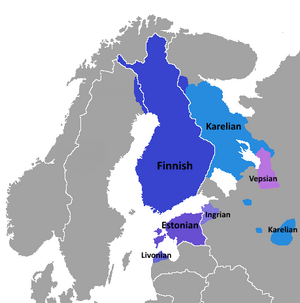

Traditional riddles from the countries where Finnic languages are spoken, like modern Finland, Estonia, and parts of Western Russia, are quite similar. However, areas in eastern Finland show some influence from Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavic riddles. In Finnish, the word for 'riddle' is arvoitus (plural: arvoitukset). This word is related to the verb arvata, which means 'to guess'.

These riddles are some of the oldest examples of Finnic literature that we still have today. Finnic riddles are special because they use unique images and ideas. They also show a mix of influences from both Eastern and Western cultures. In some areas, people even played a special riddle-guessing game.

The Finnish Literature Society has collected over 117,000 Finnish riddles from old traditions. Some of these riddles are even in the old Kalevala metre style of poetry. The Estonian Folklore Archives hold about 130,000 older traditional riddles. They also have around 45,000 other types of word puzzles.

Contents

What Finnic Riddles Look Like

Most traditional Finnish and Estonian riddles are made of two simple statements. They usually don't ask a direct question like "What is the thing that...?" Instead, they describe something in a clever way. Their special wording makes them different from everyday talk.

For example, here's a riddle collected in Naantali in 1891:

- "The tailor goes through the village without saying good morning."

- The answer is: "A needle and thread without an end knot."

Another example from Joroinen in 1888 is:

- "The father is just being born when the sons are already fighting a war."

- The answer is: "Fire and sparks."

From Estonia, a riddle might say:

- "One goose, four noses?"

- The answer is: "A pillow."

Riddles in Kalevala Metre

Many riddles are written in the old Kalevala metre. This is a special rhythm and style of poetry. Here's an example of a famous riddle called the 'Ox-Team Riddle', collected in Loimaa in 1891:

|

Kontio korvesta tulee |

From the deep woods comes a bear |

Sometimes, riddles also hint at old myths or stories. They might mention ancient people, creatures, or places. They can also sound like other types of old poems, such as sad songs or magic spells.

How We Know About Old Riddles

Records of riddles give us some of the earliest clues about Finnish writing. The very first grammar book for the Finnish language was called Linguae Finnicae brevis institutio. It was written by Eskil Petraeus in 1649. This book included eight riddles to help explain the language.

One riddle from that book was:

- "Two golden cocks fight over a beam."

- The answer is: "Eyes and nose."

Another riddle was:

- "Taller than a tall tree, lower than the grass of the earth."

- The answer is: "A road."

Later, in 1783, a person named Cristfried Ganander published 378 riddles. His book was titled Aenigmata Fennica, Suomalaiset Arwotuxet Wastausten kansa. He believed these riddles showed how smart and creative the Finnish people were. He also thought they proved how rich and useful the Finnish language was for describing everything.

Riddles in Daily Life

Riddles were a popular way for families to have fun in the Finnish-speaking world. People enjoyed them until the 1910s and 1920s. However, new types of entertainment came along. Also, many riddles became outdated as daily life and technology changed. The old Kalevala poetry style also became less popular. As more people moved to cities, family life changed too. All these reasons led to riddles no longer being a main form of entertainment.

People usually learned riddles by heart, and often knew the answers too. So, guessing a riddle wasn't always a test of how clever you were. In many parts of Finland (but not Estonia), there was also a special riddle game. This game was even mentioned in Ganander's collection from 1783.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |