Scotland, Montgomery County, Maryland facts for kids

Scotland is a special community in Montgomery County, Maryland, in the United States. It's located along Seven Locks Road. This community has 100 townhomes and a rich history. Its roots go back to the late 1800s when people who were formerly enslaved bought land in Potomac. Most residents of Scotland are African American.

Contents

How Scotland Began

In the late 1870s and 1880s, people who had been enslaved started to buy land. This land became the Scotland community. Two important early families were the Masons and Doves. Their family members still live in Scotland today. This was one of about 40 communities that formerly enslaved people created in Montgomery County. Other historic African American communities nearby include Lincoln Park in Rockville and Lyttonsville in Silver Spring.

Until the 1920s, Scotland was known as "Snakes Den." About 50 families lived there. They often worked for farmers nearby, providing affordable labor. As farming became less common, many men in Scotland worked as laborers, drivers, trash collectors, or golf caddies for wealthy white families. Women like Geneva Mason worked as seamstresses, cooks, maids, and babysitters for white families in the area.

In 1927, the community got a Rosenwald School, which helped strengthen it. Even with this, Scotland faced many challenges. Segregation and unfair treatment meant that while surrounding white areas grew with new homes and developments, Scotland remained without basic services. Into the 1960s, the community still had no running water, no electricity, and its roads were not paved.

In the mid-1960s, the community worked together to make big changes. They built 100 new townhouses. Seventy-five of these were for rent, and 25 were privately owned. The community also set up its own self-governance, which is still in place today. In 2014, the community center was updated. Then, in 2018, the 75 rental homes got a major renovation and upgrade.

Saving Our Scotland

By the early 1960s, Scotland's homes were getting old, and its basic services were still missing. New housing projects and other developments were being built all around Scotland. People called "speculators" wanted to buy Scotland's land for new housing. Montgomery County also wanted land to expand Cabin John Park.

The area around Scotland was quickly turning into neighborhoods and shopping centers. Many residents in Scotland were struggling financially. They sometimes sold their land to speculators, even for less money than it was worth. Scotland once stretched for miles along Seven Locks Road. But by 1964, it was only 48 acres with 35 homes, many described as "shacks." Twenty-three of these homes were in such bad shape they were ordered to be torn down. The 45 families in Scotland earned about $85 a week. This was only about one-third of what most families in the county earned. By late 1964, Scotland's future looked very uncertain. A new townhouse development nearby was even going to pave over the stream that was Scotland's main water source.

In 1964, a young white woman from Bethesda named Joyce B. Siegel became involved with the Scotland community. She drove there to deliver toys for the children just before Christmas. It was her first time seeing Scotland, and she was shocked by what she saw and heard.

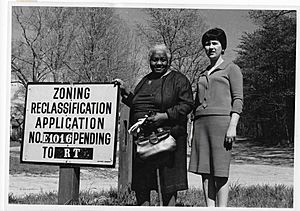

Siegel quickly started to gather support from other communities in Montgomery County. Her goal was to "Save Our Scotland." In February 1965, a formal committee was created. It included Scotland residents like Geneva Mason and Melvin Crawford, who later became the group's president. Ministers and Mrs. Siegel were also on the board. The "Save Our Scotland" group got a lot of help from faith communities.

Reverend Carl Pritchett, a pastor and president of Save Our Scotland in 1966, said, "We just feel that it is basically morally wrong for rich people, real-estate operators, and others, to drive these people out of houses just because they do not have enough money and because their skin is not white."

Many people who worked for or used to work for the U.S. government in the Washington, D.C., area volunteered their time. They brought important skills to help solve the many difficult problems Scotland faced.

One of the biggest problems was figuring out who owned the land. Many families thought they owned their land, but it turned out they only owned a small part of it. Old relatives named in wills still had a claim to the land. One man had paid taxes on land for 40 years, thinking it was his. After a very difficult search for the land titles, he found out he only owned one-eighty-seventh of the plot!

To get money from the government, the Scotland Community Development, Inc. group was formed. They received a $78,400 grant. This money paid for legal help and planning to design good housing for Scotland. The plan needed many land deals, money from the federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the old homes had to be torn down. It was a very complex process. Twenty-six different citizen groups had to agree to the necessary zoning changes.

After many years of hard work, talks, and planning, the Scotland Development Corporation took control of the land. They had about 50 acres. They planned to sell 36 acres to get money for construction. However, some partial owners of certain properties refused to agree to the project. So, the project was reduced to 10 acres.

The groundbreaking ceremony was held on April 21, 1968. Besides the money from selling 36 acres, the Corporation also got other funding. This included a $100,000 grant from the 1965 Fair Housing Act. They also received a $1.6 million loan backed by the federal government in 1967. A final $425,000 loan in 1970 helped finish the project. The completed project included 100 townhouses (25 owned and 75 for rent) on ten acres. They were finished in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These new homes replaced the old, falling-apart houses.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Robert C. Weaver visited Scotland. He told the crowd, "Scotland community is an example of how many people and groups – some who didn't get along just a few years ago – can get involved in a community's problems and work together to solve them." The main road in the new Scotland was named after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.. He had been assassinated just 18 days before. Other roads were named for David Scull, a former County Council president, and Joyce Siegel, who started the "Save Our Scotland" Committee.

Community members stayed very involved and showed strong leadership throughout the process. For example, a trip to see the Reston, Virginia, development helped them decide on changes to the roofing design for their new homes.

The Scotland project gained national attention. People noticed how the community kept control while their homes were rebuilt. The architecture also received praise. For instance, Architectural Forum magazine featured Scotland in a five-page spread.

The Scotland Community Development had an impact beyond just Scotland. Members spoke to a U.S. Senate committee about a rent-supplement program. This program was created to help the Scotland community. Members also spoke to the Maryland General Assembly to ask for tax breaks for housing non-profit groups. These tax breaks were still in place decades later.

Today, the Scotland community has a Montgomery County neighborhood community center. It was rebuilt in 2013-14 and is a very energy-efficient building. It is named after community leader Bette Carol Thompson, who passed away in 2016. The community is self-governed by the Scotland Community Civic Association. In 2018, the 75 rental units went through a $14 million renovation program.

More Than Just Homes

The "Save Our Scotland" effort and the help from outside groups also supported the community in other ways. For example, a study hall started in the basement of the community's church. This was the Scotland A.M.E. Zion Church. By 1966, the study hall was open three nights a week. Half of the community's school children attended each session. At first, most of the help came from outside volunteers. But these volunteers helped Scotland parents learn how to supervise the tutoring themselves.

Plans to Prosper You Exhibit

In 2019, the American University Museum held a summer exhibit called "Plans to Prosper You." This exhibit focused on three African American communities in Montgomery County: Tobytown, Mesopotamia, and Scotland. The exhibit included stories from Scotland residents, photos, and information about the "Save Our Scotland" activities. It also showed items from the Scotland Eagles, a team from the regional Negro baseball league.

Renaming Streets for Scotland Leaders

After a lot of research and community input, the Montgomery County Council voted in June 2021 to rename three streets. These streets were originally named after Confederate generals. Jeb Stuart Road and Jeb Stuart Court were renamed to honor Geneva Mason. She passed away in 1980 and was very important in rebuilding the Scotland neighborhood. She also helped fight against urban renewal efforts in the 1960s. Jubal Early Court was renamed for William Dove. He was born into slavery and later became one of the founding members of the Scotland community. William Dove bought some of the first pieces of land in the neighborhood, and many of his family members still live there. The streets were officially renamed on July 23, 2021.

2023 Juneteenth Celebration

In 2023, the Scotland Community held a big Juneteenth celebration. It included an art show, a film festival, a concert, and a Big Train baseball game. The baseball players even wore Scotland Eagles jerseys!

Second Century Project

The Second Century Project is working to rebuild Scotland's AME Zion Church. This project won the 2024 Legacy Award for Civic Engagement and Community Impact. This award came from the International Salute to the Life and Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |