Siege of Worcester facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Worcester |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

Worcester Cathedral from Fort Royal Hill. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Henry Washington Governor of Worcester | Edward Whalley (21 May – 8 July) Thomas Rainsborough (8 July – 23 July) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| On 29 May 1,507 strong, excluding gentlemen volunteers and the city bands. | On 29 May the Royalists thought the besieging force was about 5,000 strong, but they may have been as few as 2,500 | ||||||

The second and longest siege of Worcester happened near the end of the First English Civil War. From May 21 to July 23, 1646, soldiers from the Parliament, led by Thomas Rainsborough, surrounded the city of Worcester. They wanted the Royalist defenders to give up. On July 22, the Royalists agreed to surrender, and the Parliamentarians marched into Worcester the next day, 63 days after the siege began.

Contents

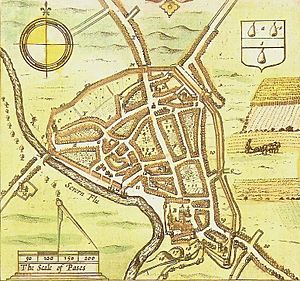

Worcester's Defenses

At the start of the English Civil War, Worcester's city walls were old and broken. Only parts of the wall had a ditch for defense. The city had seven gates, but they were weak and hard to close.

The wall ran along the river, then through different parts of the city. It crossed main streets and included important buildings. There was a weak spot where the wall left Foregate Street, which was not well protected by a ditch.

After the Royalists took control of Worcester in November 1642, they worked hard to fix the city's defenses. They built a strong point called a sconce on Castle Hill and placed cannons there. They also added strong points to the walls and dug more ditches.

A small hill to the southeast, now called Fort Royal, was a problem. From there, attackers could set up cannons and fire into the city. So, the Royalists made it part of their defenses.

Even with these improvements, Worcester was not a super strong fortress. It was about as strong as most English towns that weren't built as military forts.

Leading Up to the Siege

After the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold in March 1646, which was the last big battle of the First English Civil War, the Parliament's army started capturing the remaining Royalist strongholds.

Parliamentary forces first arrived at Worcester on March 26, 1646, and asked the Royalist governor, Henry Washington, to surrender. Washington refused. The Parliament generals didn't have enough soldiers for a full siege yet, so they left but warned Washington that his situation was hopeless.

Washington knew a siege was coming. He began to clear the area outside the city walls. He pulled down buildings that could give shelter to attackers. He also gathered supplies like firewood.

Meanwhile, King Charles I left Oxford and surrendered to the Scottish army on May 5. The Scottish commander made the King order the surrender of Newark-on-Trent, another Royalist stronghold. This showed that the King's cause was losing.

Parliamentary forces, led by Thomas Fairfax, then began to attack Oxford. They also sent troops under Colonel Edward Whalley to bother the Worcester garrison until the main army could arrive.

Before attacking Worcester directly, the Parliamentarians captured other Royalist castles nearby. Dudley Castle surrendered on May 10, and Hartlebury Castle surrendered on May 14. This left Worcester as one of the very last Royalist strongholds in the area.

The Siege Begins

May Attacks

On May 16, Fairfax demanded Worcester's surrender, but Washington refused. So, on May 21, Colonel Whalley's Parliament troops arrived and set up camp near Wheeler's Hill. Washington sent out a small group of his soldiers, but they were pushed back.

On May 24, the Royalists tried another attack, hitting Parliament's soldiers near Rogers Hill and causing some losses.

On May 25, Parliament again asked the city leaders to surrender, but they refused. The Parliamentarians then started building forts and trenches to surround the city. Inside Worcester, people began to worry about food.

On May 29, the Royalist garrison counted their soldiers. They had 1,507 men, plus gentlemen and city guards. They thought the Parliamentarians had about 5,000 soldiers. A discussion took place, but they couldn't agree on terms.

On May 31, Whalley's troops crossed the river and took control of Hallow, placing soldiers there.

June Battles

On June 1, more Parliament soldiers arrived. On June 2, a large cannon on St. Martins Gate used by the defenders burst, hurting their chief engineer. The Royalists tried to attack Hallow but failed.

On June 3, the Parliamentarians extended their defenses towards the river. Some letters were exchanged between the two sides.

On June 4, there was fighting on Pitchcroft. The city leaders ordered all tools like shovels and spades to be collected. They also brought all coal, wood, and lime into the city. People who weren't needed were sent out of Worcester.

On June 9, Parliament's soldiers moved into Henwick and St. Johns. An officer was killed, and the next day, a truce was called to return his body. During this time, a famous religious leader named Richard Baxter, who was with the Parliamentarians, talked with a Royalist chaplain.

On June 11, the Parliamentarians began firing their big cannons at the city. Some cannonballs weighed up to 31 pounds! One hit the Bishop's Palace. The Royalists also tried an attack on Henwick, but it didn't work.

On June 12, Parliament's troops took over St. Johns. At 11 PM, the Royalists made a strong attack with 500 foot soldiers and 200 horsemen. They drove the Parliamentarians out of St. Johns, killing about 100 and taking 10 prisoners. They hung the captured flags on the bridge and the cathedral.

On June 13, it was mostly quiet, but a few shots hit the town. One killed a man and his wife in their bed. Soldiers from both sides shouted insults at each other.

On June 14, Parliament finished building a bridge of boats near Pitchcroft. The Royalists still controlled the area south of Sidbury Gate, allowing them to gather hay and let their cattle graze.

On June 16, Parliament's forces paraded and lit a bonfire, trying to make the Royalists believe Oxford had surrendered.

On June 17, Parliament fired cannons at St. Martins Church. Whalley sent a deer as a gift to Governor Washington. Some citizens and their wives urged Washington to surrender, but he refused. He sent soldiers to gather more cattle.

On June 19, the Royalists found it harder to get food. Bakers refused to bake bread. A cannonball hit the mayor's house.

On June 20, the Worcester garrison learned that Madresfield, another Royalist stronghold, had surrendered. This meant Worcester was the last Royalist place left in the county.

On June 22, Washington tried to strengthen the city's northern defenses near Pitchcroft. He used poles, hurdles, earth, and horse dung to block the view of the walls. Parliament's forces also strengthened their positions around Kempsey and Barneshall, completing the encirclement of Worcester.

On June 23, the city was asked to surrender again, told that Oxford had fallen. Washington didn't believe it and asked to send a messenger to Oxford. The people of Worcester wanted to surrender, but Washington refused.

On June 25, Washington ordered a list of all food in the city. Parliament tried a trick to catch the city's cows by tying one up and making a fire around it, but it failed. Later, Prince Maurice's secretary, who had been captured at Oxford, arrived and confirmed that Oxford had indeed fallen. This meant no help was coming.

On June 26, Washington held a meeting at the Bishop's Palace. The secretary explained that Fairfax's large army was marching towards Worcester. The council decided to try and negotiate.

Negotiators were chosen from soldiers, gentlemen, citizens, and clergy. However, Fitzwilliam Coningsby, a Royalist leader, strongly opposed surrendering. Washington, a very emotional man, asked if they would fight to the last man. Coningsby said yes and wanted anyone who disagreed thrown over the walls. After much argument, they decided to vote on whether to negotiate.

Finally, a committee agreed to negotiate. An armistice (a temporary stop to fighting) was agreed upon. Washington met with a Parliamentarian colonel he knew, and they drank together. This made some people in the city angry because it allowed Parliament's soldiers to get too close to the defenses.

On June 28, Parliament's soldiers examined the city's defenses. The proposed surrender terms were sent in, causing arguments among the Royalist officers.

On June 29, a dispute arose about whether fighting should stop during negotiations. Washington, annoyed, fired a cannon himself, and the city's guns began firing, killing some Parliamentarians. When the Parliament negotiators presented their terms, they said Worcester shouldn't expect better terms than Oxford, which was a much stronger city. The Royalists said they would rather see the city burn than surrender on dishonorable terms.

July Negotiations and Surrender

By July 4, things were going badly for Worcester. It was hard to keep discipline among the soldiers. Parliament's soldiers were able to steal cattle from under the city walls because no guards were watching.

On July 8, Governor Washington announced he had to open the magazine (where weapons and gunpowder were stored). Colonel Whalley's command ended, and Colonel Thomas Rainsborough took over the siege.

On July 9, Rainsborough reviewed his forces. On July 10, Parliament's forces connected their defenses from Perry Wood to Red Hill Cross. Rainsborough started new negotiations, sending polite messages to Washington. Inside Worcester, food was becoming very scarce. Meat was very expensive.

On July 11, cannon fire from Rogers Hill caused problems. One ball hit the Town Hall.

On July 15, a small brass gun was placed on top of the cathedral. Rainsborough sent another letter offering to negotiate. Washington agreed to talk about honorable terms, and they stopped fighting for a while.

On July 16, negotiations continued. Some Royalists wanted to fight to the very end, saying Worcester was the first city to support the King and should be the last to give up.

On July 18, Rainsborough sent his final terms for surrender. Washington was told he only had enough gunpowder for an hour of fighting. The mayor called a meeting of citizens, and they agreed to accept the terms if they were the best they could get.

There was a big argument about Sir William Russell, a Royalist leader, being excluded from the surrender terms. This meant he wouldn't get the same protections as others. Washington asked if the whole city should be destroyed for one man. Russell bravely said he would surrender himself, saying he had "but a life to lose."

The gentlemen decided to write to Fairfax to ask for better terms for Russell, but the citizens disagreed. Rainsborough then wrote to Washington, saying he wouldn't allow a letter to Fairfax, but he would let delegates go to Fairfax's headquarters to see the surrender terms signed.

On July 20, two Royalist leaders went to Rainsborough's headquarters to see him sign the agreement.

On July 22, Parliament's troops in St. Johns burned their huts. Fairfax sent word that the Royalists would get passes to leave and that Sir William Russell would be treated as a gentleman.

July 23 was the last day of the siege. A final Anglican church service was held in the cathedral. Then, Washington led his soldiers and many important civilians out of the city to Rainbow Hill for the formal surrender.

There was a delay because the passes to leave hadn't arrived. Finally, at 1 PM, they received them. A Puritan minister named Hugh Peters, whom the Royalists disliked, handed them out. Each man had to promise not to fight against Parliament again to get his pass. After getting their passes, they marched away.

At about 5 PM, Rainsborough entered Worcester. This marked the end of the First Civil War for Worcestershire.

Even though the surrender terms said the Royalists could leave with their personal belongings, some Parliament soldiers robbed them. This led Parliament to order that this regiment be disbanded.

After the Siege

The Parliamentarians quickly reduced their army in Worcester. Only a small force remained to guard the sheriff.

Worcester felt the impact of being conquered. On July 24, Rainsborough ordered all weapons to be brought in. Royalist soldiers had to leave the city within ten days and were not allowed to wear swords.

The Parliamentarian committee then began to take inventory of all Royalist properties. They demanded a large payment, called a "contribution," from anyone they called a "delinquent" (someone who supported the King). Many Royalists were fined so heavily that it took them a very long time to recover financially.

This committee included many important Parliamentarian figures. They treated the Royalists of Worcestershire as conquered enemies. There was no more fighting in Worcestershire for the next five years, until the Worcester Campaign of the Third Civil War.