Richard Baxter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Baxter

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 12 November 1615 Rowton, Shropshire, England

|

| Died | 8 December 1691 (aged 76) London, England

|

| Occupation | church leader, theologian, controversialist, poet |

| Theological work | |

| Tradition or movement | Puritan, Amyraldian |

| Notable ideas | Neonomianism, Unlimited atonement |

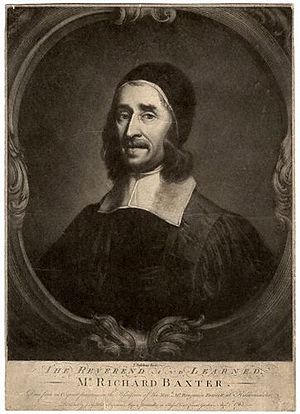

Richard Baxter (born November 12, 1615 – died December 8, 1691) was an important English church leader and thinker. He was known as a Nonconformist, meaning he didn't agree with all the rules of the official Church of England. He came from Rowton, Shropshire, and became famous for his work in Kidderminster in the 1630s. He also wrote many books about religion.

After a law called the Act of Uniformity 1662 was passed, Baxter chose not to become a bishop and had to leave the Church of England. He became a very important leader for the Nonconformists, even spending time in prison for his beliefs. His ideas about predestination are still discussed today.

Contents

About Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was born on November 12, 1615, in Rowton, Shropshire. He was baptized in High Ercall. Later, in 1626, he moved to his parents' home in Eaton Constantine.

On September 10, 1662, Baxter married Margaret Charlton. She passed away in 1681.

His Early Life and Education

Richard Baxter's early schooling wasn't very good. He was mostly taught by local church leaders who didn't have much education themselves. He got better help from John Owen, who was the head of the free school in Wroxeter. Richard studied there from about 1629 to 1632 and learned a lot of Latin.

John Owen suggested that Richard not go to Oxford, which Richard later wished he had done. Instead, he went to Ludlow Castle to study with Richard Wickstead, a chaplain.

Richard was briefly convinced to try working at the royal court in London. But he soon returned home, deciding he wanted to study divinity, which is the study of religion. His mother's death made him even more sure of this path.

After teaching for a short time, Baxter read many religious books. He studied the ideas of famous Puritan writers like Richard Sibbes and William Perkins. Around 1634, he met Joseph Symonds and Walter Cradock, who were also Nonconformists.

His Work as a Minister (1638–1660)

In 1638, with help from James Berry, Richard Baxter became the head of the free grammar school in Dudley. He began his work as a minister after being ordained (officially made a minister) by the Bishop of Worcester. Soon after, he moved to Bridgnorth, in Shropshire.

Baxter stayed in Bridgnorth for almost two years. During this time, he became very interested in the debates between Nonconformists and the Church of England. He started to disagree with the Church on several points. He didn't like the "et cetera oath" and rejected the English form of episcopacy (a church system led by bishops). Even though he was often seen as a Presbyterian (a church system led by elders), he believed that how a church was run was less important than how people practiced their faith.

Working in Kidderminster

When the Long Parliament began, one of its first goals was to improve the clergy (church leaders). People in Kidderminster complained about their vicar. The vicar agreed to pay £60 a year to a preacher chosen by local leaders. Baxter was asked to preach, and everyone chose him as their minister for St Mary and All Saints' Church, Kidderminster. This happened in April 1641, when he was 26 years old.

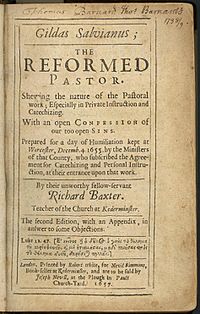

He worked in Kidderminster for about 19 years, even with many breaks. During this time, he made many positive changes in the town. He brought together ministers from different groups – Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Independents – to work together. His book, The Reformed Pastor, was about these efforts to help ministers.

The English Civil War and Commonwealth Period

When the First English Civil War started in August 1642, Baxter, like many others, tried to stay neutral. But Worcestershire was a Royalist (supporters of the King) area. So, he had to move to Gloucester, a Parliamentarian (supporters of Parliament) town. He returned to Worcestershire later in 1642 but was forced out again. He then moved to Coventry, another Parliamentarian stronghold.

In Coventry, he found many other ministers who had also fled. He served as a chaplain (a minister for soldiers) to the army garrison every Sunday. He preached to soldiers, townspeople, and visitors. After the Battle of Naseby, he became a chaplain for Colonel Edward Whalley's regiment until 1647. During these busy years, he wrote his book Aphorisms of Justification, which caused a lot of discussion when it came out in 1649.

Baxter joined the Parliamentarian army for a special reason. He wanted to stop the growth of different religious groups within the army and support the idea of a government with rules, rather than a republic. He regretted not taking Oliver Cromwell's earlier offer to be a chaplain for his famous "Ironsides" cavalry. Cromwell avoided Baxter, but when Baxter had to preach to him after Cromwell became the leader, Baxter spoke about the divisions in the church. In later talks, he even argued with Cromwell about religious freedom and defended the idea of a king. This happened when Baxter was called to London to help decide on the basic rules of religion.

In 1647, Baxter stayed at the home of Lady Rouse in Rous Lench, Worcestershire. Even though he was sick, he wrote most of his important work, The Saints' Everlasting Rest (published in 1650).

After he recovered, he went back to Kidderminster. There, he also became an important political leader. His strong beliefs often put him in conflict with almost all the different groups in the government and church. A long debate he had with John Tombes in Bewdley in 1650 was attended by about 1500 people and ended in confusion.

During this time, he also worked to create a new university in Shrewsbury for Wales. He wanted to use buildings that were part of Shrewsbury School. But the plan failed because there wasn't enough money.

Ministry After the King Returned (1660–1691)

After the king returned to power in 1660 (the Stuart Restoration), Baxter moved to London. He preached there until the Act of Uniformity 1662 became law. This law made it very difficult for moderate Nonconformists like Baxter to stay in the Church of England. His hope that they could remain part of the church did not come true. The Savoy Conference was a meeting where Baxter presented his Reformed Liturgy (a new way of conducting church services), but it was ignored. Baxter continued to argue for a unified "national church" until he died.

Baxter was as respected in London as he had been in the countryside. His preaching was powerful, and his ability to get things done made him a leader among his group. He was made a Royal chaplain and offered the chance to become the Bishop of Hereford. However, he could not accept this offer without changing his beliefs to fully follow the Church of England's rules. After he refused, he was not allowed to be a minister in Kidderminster, and Bishop George Morley stopped him from preaching in the Worcester area.

Later Writings and Final Years

Baxter's health got even worse, but this was when he wrote the most. He wrote about 168 different works! These included big books like the Christian Directory and the Catholic Theology. His book Breviate of the Life of Mrs Margaret Baxter shares the good qualities of his wife and shows how much he cared for her. A small religious book he published in 1658, called Call to the Unconverted to Turn and Live, was a very important book for evangelicalism (a type of Protestant Christianity) for many years.

The rest of his life, from 1687 onwards, was peaceful. He died in London, and both church leaders and Nonconformists attended his funeral.

Richard Baxter's Religious Ideas

Richard Baxter disagreed with the idea of a limited atonement (that Christ died only for a select few). Instead, he believed in a universal atonement, meaning Christ's death was for everyone. This led to many debates with the Calvinist thinker John Owen.

Baxter believed that Christ's death was an act of redemption for all people. Because of this, God offered a new agreement, promising forgiveness to those who felt sorry for their sins and believed. Repentance (being sorry) and faith (believing) were the conditions for salvation, according to Baxter.

Baxter felt that the Calvinists of his time were forgetting the conditions that came with God's new agreement. He believed that to be justified (made right with God), a person needed to have some faith as their response to God's love.

Baxter's religious ideas were explained in his Latin book Methodus Theologiæ Christianæ (1681). His Christian Directory (1673) contained the practical parts of his system. His Catholic Theology (1675) explained his ideas in English. His theology made him quite unpopular with some people during his time and even caused disagreements among Nonconformists later on.

His ideas differed from traditional Calvinism in four main ways:

- Christ's death was not about suffering the exact punishment deserved by humans. Instead, it was an equivalent punishment that had the same good effect. Christ died for sins, not just for certain people. The benefits of his death are available to everyone for their salvation.

- Christ's death is not limited to a small group. It is available to all who choose to believe in Christ.

- The goodness given to a believer when they are made right with God is not just Christ's goodness. It also comes from the believer's own faith in Christ.

- Every sinner has their own part to play in becoming a believer, which is to have faith in Christ.

Richard Baxter's Legacy

Richard Baxter is remembered in the Church of England on June 14.

His Writings and Mentions

A list by A.G. Matthews shows that Baxter wrote 141 books! Geoffrey Nuttall, who wrote a book about Baxter, confirmed this list.

In 1665, some of his works were translated into German.

In 1674, Baxter rewrote parts of a book called The Plain Man's Pathway to Heaven by Arthur Dent. Baxter's version was called The Poor Man's Family Book. This shows a connection between Baxter and another famous Puritan writer, John Bunyan.

Max Weber (1864–1920), a German sociologist, used Baxter's writings a lot in his famous book "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism". Weber used Baxter's idea that creating wealth can bring glory to God, as long as it doesn't lead to laziness. Baxter wrote, "you may labour to be rich for God, though not for the flesh and sin."

Robert K. Merton (1910–2003), who started the study of the sociology of science, also used Baxter's Christian Directory. He saw it as a good example of the main ideas of the Puritan way of life.

In 2015, on the 400th anniversary of Baxter's birth, letters between Baxter and Katherine Gell were shown in an exhibition. These letters were said to be the basis for a book of Baxter's letters.

Monuments and Memorials

Baxter's house in Bridgnorth is still standing near the High Street and has a plaque on it.

The Richard Baxter Monument in Wolverley and Cookley was built around 1850 to remember him. It's a Grade II listed building, meaning it's historically important. It stands on a hilltop.

The Baxter Monument in Kidderminster is also a Grade II listed building. This statue was made by Sir Thomas Brock and was revealed on July 28, 1875, almost 200 years after Baxter died. It was moved to its current spot outside St Mary's parish church in 1967.

The Baxter Monument in Rowton, Shropshire (where he was born) is a stone pillar with a bronze plaque. It says, "Richard Baxter great divine author and eminent citizen of the 17th century. Son of Richard Baxter and Beatrice née Adney born here in Rowton AD 1615. Died in London 1691." It's likely from the late 1800s and became a Grade II listed building in 1983.

There is a painting of Baxter in Dr Williams's Library in London.

Baxter House, a boarding house at Old Swinford Hospital school in Stourbridge, is named after him. In Kidderminster, Baxter College (a school) and a public park, Baxter Gardens, are both named in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Richard Baxter para niños

In Spanish: Richard Baxter para niños

- Benjamin Agus

- List of abolitionist forerunners

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |