Sino-Vietnamese characters facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sino-Vietnamese characters |

|

|---|---|

These characters mean "double happiness" for a bride and groom. They are an example of Sino-Vietnamese characters used in art.

|

|

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese | chữ Hán Nôm |

| Hán-Nôm | 字漢喃 |

Sino-Vietnamese characters (called Hán Nôm in Vietnamese) are a special type of Chinese character used in Vietnam. They can be read in two ways: either as Vietnamese words or as Chinese words with a Vietnamese sound. When these characters are used to write Vietnamese, they are called Nôm. When they are used to write Chinese, they are given a "Sino-Vietnamese" or "Han-Viet" reading. This Han-Viet system helps Vietnamese people read Chinese texts. It's a bit like how pinyin helps English speakers read Chinese.

Some of these characters are also used in China. Others are found only in Vietnam. Chinese characters first came to Vietnam when the Han Empire took over the country in 111 BC. Even after Vietnam became independent in AD 939, people continued to use Classical Chinese for official papers. In the 1920s, Vietnam started using the Latin alphabet instead of these traditional characters. Today, an organization called the Han-Nom Institute studies these old documents. They have even sent a list of almost 20,000 Sino-Vietnamese characters to Unicode so they can be used on computers.

Contents

How Vietnamese Characters Started

Chinese characters arrived in Vietnam after the Han Empire conquered the country in 111 BC. Vietnam became independent in 939 AD. But the Chinese writing system was still used for official business starting in 1010.

Soon after gaining independence, Vietnamese people began using Chinese characters to write their own language. The Van Ban bell, made in 1076, has the oldest known example of Nôm writing. A poet named Nguyen Thuyen wrote Nôm poetry in the 1200s. Sadly, none of his poems have survived. The oldest Nôm text we still have is a collection of poems by King Tran Nhan Tong from the same century.

Old Schools and New Ideas

The royal court and government used Classical Chinese for important documents. The Temple of Literature in Hanoi was a famous school for learning Chinese. Students had to pass a civil service exam, given every three years, to become government officials.

Many scholars who studied Chinese thought Nôm was not as good. But most ordinary people liked Nôm. Some kings tried to stop Nôm from being used. Other kings actually encouraged it. In 1867, King Tu Duc even made a rule to support Nôm. Not many people could read or write back then. But almost every village had someone who could read Nôm aloud for everyone else. The first Nôm dictionary was written in 1838 by Jean-Louis Taberd.

In 1910, the schools under French rule started teaching French and the new Vietnamese alphabet. This alphabet uses Latin letters with special marks for tones. On December 28, 1918, King Khai Dinh announced that the old writing system was no longer official. The last civil service exam was held in 1919. This exam system had been in place for almost 900 years! China also stopped using Classical Chinese around the same time.

How Characters Work

Chinese characters are used to write many languages. These include Mandarin, the most spoken language in China, and Cantonese, spoken in Hong Kong. They were also used in Korea and Vietnam. Japan uses Chinese characters mixed with its own writing systems.

Even if characters mean the same thing, they can be read differently in each language. For example, the character 十 means "ten" in all these languages. But it's read as shí in Chinese, jū in Japanese, sip in Korean, and thập in Vietnamese.

Most Nôm characters come from Chinese. They were chosen because they sounded similar or had a similar meaning. For example, the character for "Nôm" (喃) sounds like nán in Chinese and means "chattering." But in Vietnamese, "Nôm" just means "plain talk" or something easy to understand.

Unique Nôm Characters

Nôm also has thousands of characters that are not found in Chinese. These were created by Vietnamese writers. They put together existing parts of characters. One part, called the radical, hints at the character's meaning. The other part, called the remainder, suggests how it sounds. This is similar to how most Chinese characters are made.

Like Chinese, Vietnamese is a tonal language. This means the meaning of a word can change depending on the pitch of your voice. Japanese and Korean, however, can be written with phonetic scripts that don't show tones.

Reading Sino-Vietnamese Characters

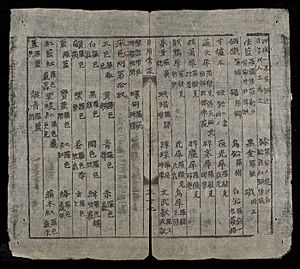

When a character is read as Vietnamese, it uses its Nôm reading. When it's read as Chinese, it can be written in Vietnamese as Han-Viet, or in English as pinyin. The table below shows some examples. The characters with a darker background are part of the main Nôm character set.

| Hán Nôm Characters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | How it's Made | How it's Read | English Meaning | Computer Code | Source | Found in Chinese? | ||

| Nôm | Han-Viet | Pinyin | ||||||

| 媄 | ⿰女美 | mẹ | mĩ | mĕi | mother | U+5A84 | V0-347E | Yes |

| 傷 | ⿰亻⿱𠂉昜 | thương | thương | shāng | to love | U+50B7 | V1-4C22 | Yes |

| 𠎬 | ⿰亻等 | đấng | đẳng | děng | Used in đấng anh hùng (heroes) | U+203AC | V2-6E62 | No |

| 𠾾 | ⿰口湿 | nhấp | thấp | shī | Used in nhấp nhổm (anxious) | U+20FBE | V3-3059 | No |

| 𫆡 | ⿰育个 | dọc | dục | yù | Used in bực dọc (frustrated) | U+2B1A1 | V4-5224 | No |

| ⿰朝乙 | giàu | triêu | cháo | wealthy | U+2B86F | V4-405E | No | |

| ⿰月報 | béo | báo | bào | fat | U+F04A5 | V+63D0A | No | |

| Key: Kangxi and HDZ (Hanyu Da Zidian) are big Chinese dictionaries. HK glyphs are characters taught in Hong Kong schools. Sources: The Unicode Consortium 1991-2013, The Unicode Consortium 2012. Nôm readings are from the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, Han-Viet is from Hán Việt Từ Điển, and pinyin is from Purple Culture. |

||||||||

Characters on Computers

In 1994, a group called the Ideographic Rapporteur Group decided to add Sino-Vietnamese characters to Unicode. Unicode is a system that allows computers to show text from different languages.

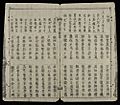

Between 1993 and 2001, the Han-Nom Institute gathered 9,299 "Nôm Ideographs" into four groups (V0, V1, V2, and V3). Each Sino-Vietnamese character gets a special "V Source code" and then a "codepoint." These codes help computers send and save the characters. To see them correctly, you need to have the right font installed on your computer.

These Nôm Ideographs came from two dictionaries published in the 1970s. A book called The Hán Nôm Coded Character Repertoire (2008) combines the work of the Han-Nom Institute with another group. This book lists almost 20,000 Sino-Vietnamese characters. It includes the main Nôm Ideographs, different ways characters were written in old manuscripts, characters used by the Tay people, and many Chinese characters with their Han-Viet readings.

| Group | Number of Characters | Unicode Block | Standard | Year | Example | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V0 | 2,246 | Basic Block (593), A (138), B (1,515) | TCVN 5773:1993 | 2001 | 𨒒 mười (ten), U+28492 | Vũ Văn Kính & Nguyễn Quang Xỷ 1971 |

| V1 | 3,311 | Basic Block (3,110), C (1) | TCVN 6056:1995 | 1999 | 喜 hỷ (happiness), U+559C | Vũ Văn Kính & Nguyễn Quang Xỷ 1971, Hồ Lê 1976 |

| V2 | 3,205 | Basic Block (763), A (151), B (2,291) | VHN 01:1998 | 2001 | 𣃤 vừa (fit, match), U+230E4 | |

| V3 | 535 | Basic Block (91), A (19), B (425) | VHN 02:1998 | 2001 | 𠁙 chả (not), U+20059 | Manuscripts |

| V4 | 785 | Extension C | The V4 set has 2,230 characters, split between extensions C and E. | 2009 | 𪝌 bị (to get), U+2A74C | Vũ Văn Kính 1994, Hoàng Triều Ân 2003, Nguyễn Quang Hồng 2006 |

| V4 | 1,028 | Extension E | 2015 | |||

| V5 | ~900 | This group was suggested in 2001, but the characters were already encoded. No V Source was added. | 2001 | 㦸 kích (spear), U+39B8 | Vũ Văn Kính & Nguyễn Quang Xỷ 1971, Hồ Lê 1976 | |

| V6 | ~8,000 | Basic Block, Extension A | Assembled by the Nôm Na Group. Most are Chinese characters already encoded. | Projected | 鎄 ai (einsteinium), U+9384 | Trần Văn Kiệm 2004 |

| Sources: Nguyễn Quang Hồng 2008, The Unicode Consortium 1995-2013, and The Unicode Consortium 2012 | ||||||

Images for kids

-

The Nôm character for phở, a popular noodle soup. The left part of the character suggests it's related to rice. The right part suggests its sound.

See also

In Spanish: Chữ Nôm para niños

In Spanish: Chữ Nôm para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |