Stratton's Independence Mine and Mill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Stratton's Independence Mine and Mill

|

|

Image from the George H. Stone Collection of Colorado geological features and views, Special Collections, Tutt Library, Colorado College.

|

|

| Location | Junction of Rangeview Road and State Highway 67, Teller County, Colorado |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Victor, Colorado |

| Built | 1891 |

| NRHP reference No. | 93000054 |

| Added to NRHP | 1993-03-04 |

The Stratton's Independence Mine and Mill is a famous old gold mining spot near Victor, Colorado. It sits on the side of Battle Mountain. From late 1893 to April 1899, this mine produced a huge amount of gold – about 200,000 ounces! That's like 6,200 kilograms of gold.

Contents

History of the Mine

How the Mine Started

In 1891, a man named W. S. Stratton got help from Leslie Popejoy to start looking for gold in the Cripple Creek area. They agreed to share any profits. On July 4, 1891, Stratton claimed two spots on Battle Mountain. He named them the Independence and the Washington, celebrating the holiday.

Stratton soon sold his house and some land to buy out Popejoy's share. He did this because early tests from the Independence mine showed a lot of gold. One large rock from the Independence mine was worth $60,000! Stratton used this money to dig deeper, and he quickly found a very rich vein of gold. The next year, in 1892, he also found gold in the Washington mine. Stratton became the first millionaire from the Cripple Creek District.

Miners and Their Rights

In 1894, miners in Cripple Creek went on strike. Stratton's Independence mine and another mine called Portland agreed to work with the miners. This was different from what other mine owners wanted. Stratton was also the first president and a big owner of the Portland company.

Mine companies worried about gold being stolen. In 1897, they started hiring detectives from the Pinkerton agency to help prevent theft.

Selling the Mine

In 1900, Stratton sold the Independence mine to a company from London for $10 million. The company renamed it Stratton's Independence Ltd and sold shares to people in London. But soon, they found there wasn't as much gold as they thought. The company's share price dropped a lot. They even sued Stratton, saying he had tricked them. Stratton died in 1902, but his family won the lawsuit.

Later in 1900, union representatives visited the Independence mine. Most miners were part of the union, but a few were not. The union members didn't want to work with non-union miners. The mine superintendent convinced the non-union workers to join the union to keep things peaceful.

New Rules and Protests

In September 1900, the Independence mine was the first in the area to try a new rule. All underground workers had to change clothes in one room and walk into another room without clothes while a guard watched. This was meant to stop workers from stealing gold ore.

Five hundred miners met and decided they would help stop theft, but they refused to work under this new rule. They reached a compromise: miners could keep their underwear on during searches. But the miners were still unhappy. After about a month, a Pinkerton detective searched miners at the end of a shift. No gold was found, and the miners walked out.

Three days later, the mine manager met with the union leaders. He agreed to stop using Pinkerton guards and let the union suggest a guard for the changing rooms. He also agreed to hire only union members. Under this deal, if a miner was suspected of stealing, another union member could search them with a watchman present. The manager also said he would support miners joining the union if the union helped stop gold theft.

In 1902, the miners at the Independence mine even bought diamond rings for the manager and other leaders who had worked with them. They all had a friendly meeting after the gifts were given.

Colorado Labor Wars

In 1903, there was a big strike by the Western Federation of Miners. Many miners in the Cripple Creek area stopped working at mines that sent gold to mills in Colorado City. They did this to support mill workers who were also on strike there.

Mine Accident

On January 26, 1904, a terrible accident happened at the Independence Mine. Workers who were not part of the union were leaving their shift. They were riding in a cage that moved up and down the mine shaft. The cage went too high and hit the wheel at the top of the shaft. The cable holding the cage broke, and the cage fell. Fifteen miners fell 1,500 feet down the shaft.

Investigators looked into the safety equipment and the skills of the person operating the hoist (the machine that moved the cage). One miner, James Bullock, survived the accident. He told the jury what happened:

... We kept going right along but it kept slipping; we would go a little ways and then we would slip again; then he took us about six feet above the collar of the shaft, then he lowered us back down.

Q. Did he stop six feet above the shaft?

A. He stopped just for a second or two; then he lowered us and it must have gotten beyond his control, for we dropped about sixty or seventy feet, we were going pretty. [sic] We said to each other we are all gone. Then he raised us up about ten feet; then he stopped us and it slipped back again, and we went to the sheave wheel as fast as we could go. When I was going up there, I began to crouch to save myself from the hard blow. I seen a piece of timber about one foot wide, and I grabbed hold and held myself up there and pretty soon the cage dropped and I began to holler for a ladder to get down.

The person operating the hoist also described the event:

I tried several times, but that time the cage was at the collar of the shaft. I immediately reversed the engine and sent the cage back 100 feet. I again tried the brakes, reversed the engine, and brought the cage back to the surface. The brake was still stuck; I could not move it. I again reversed the engine and sent the cage back about the same distance and stepped over to the other side and took hold of the other brake, and it was in the same condition. The second time the cage came to the surface, I called three times for the shift boss, for God's sake come and help me put on the brakes. In the meantime, I was reversing the engine backwards and forwards. Mr. MacDonald came and two other men with him. I said come up and help me put on the brakes, and then I discovered the hood of the cage above the collar of the shaft. I immediately reversed the engine, but it was too late.

The jury found that the brakes had been checked just six hours before the accident and were working afterward. They questioned another hoist operator who said that the employer had only taken the operator's word about his skills. The report said the operator lost control because the mine management had not installed a safety device to stop the cage from going too high. Also, the backup brakes on the hoist engine had been removed.

The union said the accident was due to bad management. Even though soldiers guarded the mine, management blamed the union for messing with the machinery. After this accident, 168 non-union workers reportedly quit the Independence Mine. Just a few months later, after more violent events, the union was forced out of the area. This struggle became known as the Colorado Labor Wars.

Mine Geology

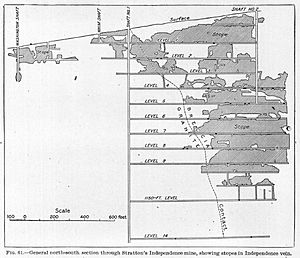

The Washington mine claim was in granite rock. The Independence mine, however, was in a type of rock called breccia, which was better for finding gold. By 1894, the Independence shaft was 70 feet deep and produced 800 tons of gold ore each month. Each ton had about 3.5 ounces of gold. In 1895, the shaft reached 300 feet deep. By 1897, when the Venture Corporation bought the mine, the shaft was 900 feet deep.

Another type of rock called phonolite runs through both the granite and breccia. Often, gold is found in these phonolite rocks. It usually appears as a mineral called calaverite in very thin cracks, along with fluorite and quartz.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |