Táin Bó Cúailnge facts for kids

The Táin Bó Cúailnge (pronounced "Tawn Boh Koo-lin-geh"), often called The Táin or The Cattle Raid of Cooley, is a famous epic story from Irish mythology. People sometimes call it "The Irish Iliad" because it's a long, important tale about heroes and war. Unlike many epics, the Táin mixes prose (like a regular story) with poetry spoken by the characters.

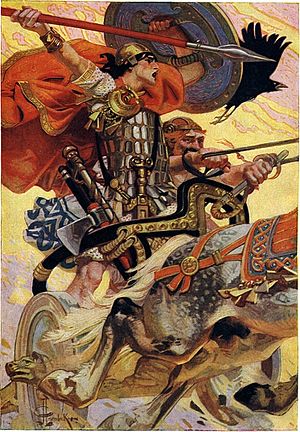

The story tells of a big war against the land of Ulster. Queen Medb of Connacht and her husband King Ailill start this war. They want to steal a special bull named Donn Cuailnge. But there's a problem: a curse makes the Ulster warriors unable to fight. So, a young hero, Cú Chulainn, has to defend his land all by himself.

The Táin is set a very long time ago, around the 1st century, in a time of ancient heroes. It's the most important story in a group of tales called the Ulster Cycle. We know the story from three main written versions. These versions were copied down in books from the 12th century and later.

This epic has had a huge impact on Irish stories and culture. Many people see it as Ireland's national epic.

Contents

The Great Cattle Raid Story

Before the main story of the Táin begins, there are several shorter tales called remscéla. These are like background stories. They help us understand the main characters and why certain things happen. For example, they explain why some Ulster warriors are fighting with Queen Medb. They also tell us about the curse that stops the Ulster men from fighting. And they explain how the two special bulls, Donn Cuailnge and Finnbhennach, got their magical powers.

The story starts with King Ailill and Queen Medb comparing how rich they are. Medb realizes that Ailill has a super-fertile bull named Finnbhennach. This bull was once hers, but it didn't want to be owned by a woman, so it joined Ailill's herd. Medb decides she must have a bull just as good to be equal to her husband. She sets her sights on Donn Cuailnge, a powerful bull from Cooley.

Medb first tries to rent Donn Cuailnge from his owner, Dáire mac Fiachna. But her messengers accidentally reveal that Medb plans to take the bull by force if she can't borrow him. The deal falls apart. So, Medb gathers a huge army. This army includes some warriors from Ulster who were exiled, led by Fergus mac Róich. They march off to capture Donn Cuailnge.

Meanwhile, the men of Ulster are hit by a strange illness. It's called the ces noínden, which means "debility of nine days," but it lasts for months. This illness is a curse from the goddess Macha. She put the curse on Ulster after their king forced her to race against a chariot while she was pregnant. Because of this curse, only one person is able to fight: the young, brave Cú Chulainn, who is just seventeen years old.

Cú Chulainn is supposed to guard the border, but he's off meeting someone and misses the army's arrival. So, Medb's army takes Ulster by surprise. Cú Chulainn, with help from his charioteer Láeg, starts a one-man war. He uses clever tricks and fights many single duels at river crossings. He defeats champion after champion, stopping the army for months. But even with his amazing skills, he can't stop Medb from capturing the bull.

Cú Chulainn gets help and trouble from magical beings called the Tuatha Dé Danann. Before one fight, the Morrígan, a goddess of war, comes to him as a beautiful woman and offers her love. Cú Chulainn turns her down. She then shows her true form and threatens to mess up his next fight. She does this by turning into an eel, then a wolf, and finally a heifer. Each time, Cú Chulainn wounds her. After he wins his fight, the Morrígan appears as an old woman. She has the same wounds Cú Chulainn gave her. She offers him milk, and with each drink, he blesses her, healing her wounds. Cú Chulainn tells her he wouldn't have refused her if he had known who she was.

After a very hard fight, Cú Chulainn is visited by another magical figure, Lugh. Lugh tells Cú Chulainn that he is his father. Lugh then puts Cú Chulainn to sleep for three days to heal him. While Cú Chulainn sleeps, a group of young Ulster warriors comes to help, but they are all killed. When Cú Chulainn wakes up, he goes through a terrifying change called a ríastrad or "distortion." His body twists, and he becomes a monster who can't tell friends from enemies. Cú Chulainn attacks the Connacht camp fiercely, getting revenge for the young warriors.

After this amazing event, the single combats continue. Sometimes, Medb breaks the rules by sending many men against Cú Chulainn at once. When his foster-father, Fergus, is sent to fight him, Cú Chulainn agrees to let Fergus win, as long as Fergus lets him win the next time they meet.

Finally, Medb convinces Cú Chulainn's foster-brother, Ferdiad, to fight him. She promises Ferdiad her daughter's hand in marriage and threatens to have poets mock him if he refuses. Cú Chulainn doesn't want to kill his foster-brother and begs him not to fight. But they have a long, tough three-day duel. Cú Chulainn wins, killing Ferdiad with his special spear, the Gáe Bulg. Cú Chulainn is badly wounded and is carried away by healers.

Slowly, the Ulster warriors start to recover from their illness. First one by one, then all at once. King Conchobar mac Nessa promises to bring every cow and every captured woman back home. The final, huge battle begins.

At first, Cú Chulainn stays out of the fight, recovering. Fergus has King Conchobar helpless, but Conchobar's son, Cormac Cond Longas, stops Fergus from killing him. In his anger, Fergus cuts the tops off three hills with his sword. Cú Chulainn quickly recovers from his wounds and joins the battle. He faces Fergus and makes him keep his promise to yield. Fergus pulls his forces out of the fight. Connacht's other allies panic, and Medb has to retreat. Cú Chulainn finds Medb and spares her life, even guarding her as she retreats.

Medb manages to bring Donn Cuailnge back to Connacht. There, Donn Cuailnge fights Finnbhennach, the other great bull. Donn Cuailnge kills Finnbhennach but is badly hurt himself. He wanders around Ireland, leaving pieces of Finnbhennach from his horns, which create new place names. Finally, he returns home and dies from exhaustion.

How the Story Was Kept Alive

Oral Storytelling

The Táin was first told as stories by people speaking them aloud. It was only written down much later, during the Middle Ages.

Some experts believe parts of the Táin were told orally for a very long time before anyone wrote them down. For example, a poem from around 600 AD talks about Fergus mac Róich's exile. The poet says this story came from "old knowledge." Other poems from the 7th century also mention parts of the Táin. This shows the story was well-known long ago.

People thought the written story was very important. A saying from the 9th century said that the Táin was one of Ireland's wonders. It even said that a dead person (Fergus mac Róich) told the story to a living poet!

Over the centuries, different versions of the epic have been collected from people who still told the stories. More recently, a version of the Táin was written down in Scottish Gaelic from a storyteller in Scotland.

Written Copies

Even though the oldest copies we have are from the 12th century, a version of the Táin might have been written down as early as the 8th century.

The Táin Bó Cúailnge exists in three main written versions, called "recensions."

- The first version is found in two old books: the Lebor na hUidre (from the late 1000s/early 1100s) and the Yellow Book of Lecan (from the 1300s). By combining these two, we can get a full story. This version mixes different older tales. Some parts are very well written, but others are short summaries, making it a bit jumbled. Some parts of this version might be from the 700s, and some poems in it could be even older.

- The second version is in the Book of Leinster (from the 1100s). A scribe (a person who copied books) put together the stories from the first version and other unknown sources. This created a more complete and flowing story. However, the language in this version is much fancier and less direct than the older one.

An incomplete third version also exists from the 12th century.

The Táin in Books and Art

Many people have translated and adapted the Táin over the years. The first full English translation was in 1904 by L. Winifred Faraday. Before that, some parts were translated, and many writers used the story as inspiration.

Famous Irish writers like W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory wrote their own versions or stories based on the Táin. Lady Gregory's Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1903) is a well-known retelling of the tale.

More recently, two Irish poets, Thomas Kinsella (1969) and Ciarán Carson (2007), have made popular translations. Kinsella's translation includes beautiful illustrations by Louis le Brocquy.

Some older translations changed parts of the story. They might have left out details that seemed too rough or funny for their time. This was sometimes done to make the hero, Cú Chulainn, seem more perfect. However, later translations, like Kinsella's, tried to include all parts of the original story more accurately.

Background Stories (Remscéla)

The main story of the Táin relies on many separate background stories, called remscéla. Some of these might have been created on their own and then linked to the Táin later. Here are some important ones:

- De Faillsigud Tána Bó Cuailnge (How the Táin Bó Cuailnge was found): This tells how the story of the Táin was lost and then found again.

- Táin Bó Fraích (The Cattle Raid of Froech): This gives background on Froech mac Idaith, a warrior Cú Chulainn fights in the Táin.

- Aislinge Oengusa (The Dream of Oengus): This story explains why the magical being Oengus helped Medb and Ailill in their cattle raid.

- Compert Con Culainn (The Conception of Cú Chulainn): This tells the story of how Cú Chulainn was born.

- Longas mac nUislenn (The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu): This explains how Fergus and other Ulster warriors ended up fighting with Queen Medb's army.

- Ces Ulad (The Debility of the Ulstermen): This explains the curse from the goddess Macha that made the Ulster men unable to fight.

Cultural Impact

The Táin has inspired many artists and musicians. For example, in 2004, the indie rock band The Decemberists released a five-part song called The Tain. This song loosely tells the story of the Táin Bó Cúailnge.

See also