The Owl and the Nightingale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Owl and the Nightingale |

|

|---|---|

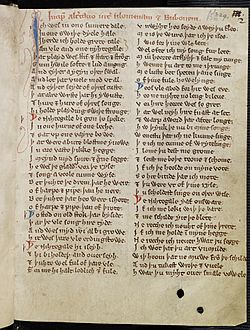

| Altercatio inter filomenam et bubonem | |

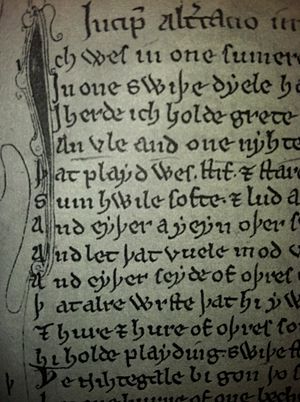

Opening page of The Owl and the Nightingale: Oxford, Jesus College, MS. 29, fol. 156r

|

|

| Also known as | Hule and the Nightingale |

| Date | 12th or 13th century |

| Manuscript(s) | (1) British Library Cotton MS Caligula A IX; (2) Oxford, Jesus College, MS 29. Written in the 2nd half of the 13th century |

The Owl and the Nightingale (Latin: Altercatio inter filomenam et bubonem) is a very old poem from the 12th or 13th century. It was written in Middle English, which is an older form of the English language. The poem is about a big argument between an owl and a nightingale. A narrator (the person telling the story) overhears their whole debate.

This poem is special because it's the earliest example of "debate poetry" in Middle English. Debate poetry is a type of poem where two characters argue about something. Back then, most debate poems were written in Anglo-Norman (a French language spoken in England) or Latin. This poem shows how French ideas and writing styles influenced English poetry. After the Norman Conquest, French became a very important language in England. But English was still widely used, especially for fun or silly poems like this one.

Contents

Who Wrote It and When?

It's a bit of a mystery who wrote The Owl and the Nightingale. We also don't know exactly when it was first written.

Searching for the Author

The poem mentions a person named Nicholas of Guildford several times. The birds say he would be the best judge of their argument. Nicholas never actually appears in the poem. The story ends with the owl and nightingale flying off to find him. Some people think Nicholas of Guildford might have been the author. However, there's no strong proof that he wrote it. We don't even know for sure if a "Nicholas of Guildford, priest of Portesham," really existed outside of the poem itself.

Some scholars have also wondered if the poem was written by a group of nuns for other religious women to read.

Pinpointing the Poem's Age

It's also hard to say exactly when The Owl and the Nightingale was first created. We only have two copies of the poem that survived. These copies were made in the second half of the 13th century. They were probably copied from one original poem that is now lost.

In the poem, the nightingale prays for "king Henri." This could mean either Henry II of England, who died in 1189, or Henry III of England, who died in 1272. Most experts believe the poem wasn't written much earlier than the copies we have. So, it likely comes from the 12th or 13th century. Some even think it was written after Henry III died in 1272.

Where Did It Come From?

Experts have looked at the language used in the poem. They think it might have come from Kent or a nearby area in England. But there isn't much evidence to fully support this idea. Because we can't date the poem exactly, it's hard to know for sure what specific dialect (local way of speaking) it was written in. More recent studies suggest it could have come from Wessex, the Home Counties, or the south-west Midlands.

The Surviving Manuscripts

We know of two old copies, called manuscripts, of The Owl and the Nightingale.

- One is found in Jesus College, Oxford, MS. 29.

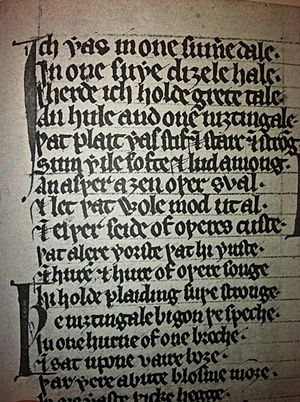

- The other is in the British Library, Cotton MS. Caligula A. ix.

Both manuscripts are bound together with other writings. They were both likely copied in the late 13th century from the same original poem, which is now lost.

Jesus College, Oxford, MS. 29

This manuscript was given to Jesus College between 1684 and 1697. It contains 33 different texts in English, Anglo-Norman, and Latin. All the writing in this manuscript looks like it was done by the same person. The style is simple and not very fancy. The Owl and the Nightingale part is written in two columns. Some capital letters are in blue and red, but there are no detailed pictures or decorations.

Cotton Caligula A.IX

This manuscript has 13 texts in English and Anglo-Norman. Most of these texts were probably put together from the start. The writing was done by at least two different scribes (people who copied texts). It's also in two columns. Some capital letters are red, but there are no detailed pictures. The writing style is professional and neat. This manuscript has a binding from the 1800s. We don't know who owned it before then.

What Happens in the Poem?

The poem is all about a big, heated argument between the owl and the nightingale. The narrator just listens to them.

The Argument Begins

When the narrator first finds them, the Nightingale is sitting on a branch full of blossoms. The Owl is on a branch covered in ivy. The Nightingale starts the fight by insulting the Owl's looks. She calls the Owl ugly and dirty. The Owl suggests they argue politely and calmly. The Nightingale then says they should ask Nicholas of Guildford to judge them. She says he's a good judge now, even though he was silly when he was younger.

But the Nightingale immediately goes back to insulting the Owl. She makes fun of the Owl's screeches and shrieks. She says the night, when the Owl is active, is full of bad things and hate. The Owl replies that the Nightingale's constant singing is too much and boring.

Birds' Different Views

The Nightingale argues that the Owl's song brings sadness. Her own song, she says, is joyful and shows the beauty of the world. The Owl quickly points out that Nightingales only sing in summer. She says that's when people are thinking about silly things. Also, the Owl claims, singing is the Nightingale's only skill. The Owl says she has more useful skills, like helping churches by getting rid of rats.

The Nightingale says she also helps the Church. Her songs, she claims, remind people of Heaven's glory. They encourage churchgoers to be more religious. The Owl disagrees. She says that before people can reach Heaven, they must say sorry for their sins. Her sad, haunting song makes people think about their bad choices. The Nightingale argues that women are naturally weak. She says any sins they commit when they are young are forgiven once they get married. She blames men for taking advantage of young women.

The Fight Continues

The Nightingale then says the Owl is only useful when she's dead. Farmers, she says, use the Owl's dead body as a scarecrow. The Owl tries to make this sound good. She says she helps people even after she dies. But the Nightingale doesn't accept this answer. She calls other birds to make fun of the Owl. The Owl threatens to call her friends, who are birds of prey.

Before the fight gets worse, a Wren flies down to calm them. The birds finally decide to let Nicholas of Guildford judge their case. He lives in Portesham in Dorset.

The Unfinished Debate

There's a short part in the poem about how great Nicholas is. It says it's a shame that bishops and rich men don't appreciate him or pay him enough. The Owl and Nightingale agree to find this wise man. The Owl says her memory is so good that she can repeat every word of their argument when they arrive. However, the reader never finds out which bird wins the debate. The poem ends with the two birds flying off to find Nicholas.

How the Poem is Written

Style and Form of the Poem

The poem is made up of rhyming pairs of lines, called couplets. Each line usually has eight syllables. This style is called iambic tetrameter.

[lines 437–442] |

|

Using iambic tetrameter can make a poem flow nicely and be easy to read. But it can also become boring if it's too repetitive. The poet avoids this by changing the rhythm sometimes. They might add or remove a syllable here and there. The poem also uses lots of vivid descriptions, repeating sounds (like alliteration and assonance), and strong images.

[lines 13–18] |

|

The language in the poem isn't overly complicated or fancy. The birds talk like everyday people. Their insults are sharp and direct. The comparisons they use are often from country life. For example, the Nightingale compares the Owl's chattering to the rough speech of an Irish priest. They also talk about fox hunts and how scarecrows are used.

What Kind of Poem Is It?

Medieval debate poetry was very popular in the 12th and 13th centuries. This poem uses the same structure as these debates. It's like a legal case from that time. Each bird makes an accusation against the other. Then, they try to provide evidence to support their claims. They even quote old sayings as if they are strong evidence.

However, the birds' arguing skills are not very good. They try to win by making the other bird seem small or silly. They also compare their opponent's habits to unpleasant people or things.

[lines 71–74] |

|

The animals defend themselves by praising their own actions. Each bird tries to show how helpful or good their own behaviors are. But the Owl criticizes the Nightingale for something she does herself. And the Nightingale's defense uses the same kind of logic as the Owl. Both birds use their songs to encourage good religious thoughts and actions. The Nightingale says her song sounds like the beautiful music of heaven.

[lines 736–742] |

|

The Owl, on the other hand, tries to make people feel bad about their sins. She warns them about what will happen if they keep sinning.

[lines 927–932] |

|

Where to Read More

You can find copies of the poem online:

- Here

- Here, here, here and here