The Philadelphia Tribune facts for kids

| Type | African American daily |

|---|---|

| Owner(s) | The Philadelphia Tribune Company, Inc. |

| Founder(s) | Christopher James Perry, Sr. |

| Founded | November 27, 1884 |

| Language | English |

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| City | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Country | United States |

| Circulation | 31,544 weekday 23,698 Sunday (as of September 2020) |

| ISSN | 0746-956X |

The Philadelphia Tribune is the oldest newspaper in the United States that has always been published by and for African Americans. It started way back in 1884.

Since it began, The Philadelphia Tribune has worked hard to help African Americans in the Philadelphia area. It focused on their social lives, politics, and economic success. When African Americans faced many challenges to gain equal rights, the Tribune became known as the "Voice of the black community" in Philadelphia. One historian, V. P. Franklin, said the Tribune was a very important place for Black culture in Philadelphia. It showed the values of Black people from all walks of life.

Today, the newspaper is located at 520 South 16th Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It comes out on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Sundays. The Philadelphia Tribune also publishes other magazines like Tribune Magazine and Entertainment Now. The Tribune serves the Philadelphia and Camden areas, plus Chester. It has won the John B. Russwurm award for "Best Newspaper" seven times since 1995.

Contents

Who Was Christopher James Perry?

Christopher James Perry Sr. (born September 11, 1854 – died May 15, 1921) was an African American journalist. He was the person who started The Philadelphia Tribune. Before this, Perry wrote for other newspapers in Philadelphia, like the Sunday Mercury. But in 1884, that newspaper closed, and Perry lost his job.

Later that year, on November 27, 1884, Perry started his own newspaper, The Philadelphia Tribune. He did everything himself: he was the owner, reporter, editor, and even handled the advertising. Perry worked on the Tribune until he passed away in 1921. During his time with the Tribune, he always worked to help African Americans move forward in society. He also wrote about the issues that affected their daily lives.

The History of the Tribune

How the Newspaper Started

When the Tribune first started in 1884, it was a weekly paper with just one page. It was printed from 725 Sansom Street. Even though Black businesses faced many difficulties in the late 1800s, especially in journalism, the Tribune was very successful early on. By 1887, it was printing about 3,225 copies every week.

In 1891, Perry and the Tribune became known across the country. This happened when Garland Penn, a famous supporter of African-American journalism, praised the Philadelphia newspaper in his book The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. Penn said the Tribune was always consistent and reliable.

The Tribune was not the only African-American newspaper in Philadelphia at that time. It competed with others like The Philadelphia Standard Echo and The Philadelphia Sentinel. But by 1900, the Tribune became the most important voice for Black Philadelphia. W. E. B. Du Bois, a famous writer and activist, even called it "the chief news-sheet" in the city.

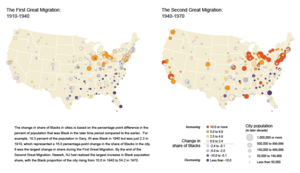

The Great Migration and the Tribune

Around 1910, many more Black migrants moved to Philadelphia. This was part of the Great Migration, where people moved from the rural South to big industrial cities in the North. Many new workers were drawn by the expansion of railroads. When World War I started, industries began hiring Black workers as white men joined the military.

The city became very crowded. New migrants moved into neighborhoods where white people lived. This sometimes led to violent reactions in working-class areas. White groups sometimes formed to scare Black families. In 1914, a white group attacked and destroyed a Black woman's new home. But the Philadelphia Department of Public Safety did not investigate, and no white newspapers reported it.

The managing editor of the Tribune, G. Grant Williams, reported the case. He encouraged African Americans to join the police force and help shape the city. The newspaper worked with the Colored Protective Association to help defend African Americans who were unfairly arrested. Williams also wrote articles about how to protect women from racial violence. He also gave advice on good morals and values. To help create a shared culture and unity among Black people in the city, the Tribune advertised free lectures. It also invited respected church leaders to write columns for the paper.

As white men left the city for war in Europe, industrial jobs opened up for African Americans. The Tribune reported on these job opportunities. However, after the war ended in 1918, white soldiers returned. They competed strongly with African Americans for jobs during a time when the economy was slowing down. Racial riots broke out in the summer of 1919 in many industrial cities. Since white men often seemed more qualified for work, the Tribune spent the 1920s encouraging African Americans to get an education or learn a trade at a special school.

By 1920, the Tribune was printing 20,000 newspapers every week. It was known as one of the best African-American newspapers in the country. In 1921, its founder, Christopher Perry, passed away. G. Grant Williams took over. Williams died in June 1922. Eugene Washington Rhodes then became the managing editor. He served for over twenty years until 1944. Under Rhodes, the Tribune looked better. The print size and column size became larger. Even though the price went up, the Tribune was still very popular.

The Great Depression and New Deal Era

In April 1929, before the Stock Market Crash, the unemployment rate for Black people in Philadelphia was 45 percent higher than for white people. During the Great Depression, African Americans in Philadelphia and across the country faced even higher unemployment. This was often because they had fewer job skills or qualifications.

Rhodes and the Tribune wrote articles to help African Americans improve their lives during these hard times. The newspaper shared information about relief help. It advertised Black social organizations, churches, and schools. Also, by 1930, the Tribune and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Philadelphia would report unfair hiring practices by local businesses. This negative attention would pressure businesses to change how they hired people.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt started his New Deal program in 1933, the Tribune reported on the new government help. It also showed how some of these programs treated African Americans unfairly. The Tribune faced a difficult choice. Historically, the Tribune had supported the Republican Party. This was because of its ties to Abraham Lincoln and the Abolitionists who fought to end slavery. To keep Republicans in power locally and statewide, Rhodes and the Tribune stayed loyal to the Republican Party. They criticized Roosevelt and his Democratic Party.

The mixed messages from the Tribune allowed other African-American newspapers in Philadelphia to gain readers. In 1935, the Philadelphia Independent openly supported Roosevelt and the Democrats. It became more popular than the Tribune, with 30,000 weekly readers. In the mid-1930s, Rhodes added new features to the paper to attract more readers. He added an editorial section that highlighted African-American achievements. He also added a comic strip to the weekly paper.

The Tribune's Basketball Team

Women's basketball became popular in Philadelphia when many young African American women moved to the city during the Great Migration. Teams were formed by neighborhoods or local YWCAs. These YWCAs offered classes and sports teams to help the new migrants learn skills.

During the Great Depression in 1931, The Philadelphia Tribune decided to create a women's basketball team. The newspaper had supported women's sports for over ten years. It had also sponsored a men's basketball team since 1929.

On November 13, 1931, the Philadelphia Tribune Newsgirls played their first game. This was at the Catherine Street YWCA in Philadelphia. The starting players were Ruth Lockley, Ann Carrington, Rose Wilson, Louise Hall, and Louise "Dick" Hill. The Newsgirls' best game of their first season was the city Championship against the German Town Hornets. The Newsgirls finished their first season with 31 wins and 5 losses. They also won the National Colored Championship title. For the next season, the Newsgirls added Ora Washington, who was considered the best female player at the time. The Tribune Girls continued to be very successful in women's basketball for several years.

The Newsgirls won many city and national championships during their eleven years, from 1931 to 1942. Otto Briggs, their coach, had to leave his position at the Tribune because of his health. Robert Bryant became the new coach for the 1941–42 season. Bryant was a minister and was called to serve as an army chaplain. The Tribune girls continued their season, but it ended up being their last. Coach Otto Briggs passed away on October 27, 1943. His death, along with readers becoming more interested in World War II news than basketball, led to the end of one of the most successful African American women's basketball teams ever. Otto Briggs made a big impact on African American women's basketball by using The Philadelphia Tribune to promote the sport.

The Tribune Girls used new training methods. They focused on physical fitness and smart gameplay. This made them stand out from other teams. Their tough practice schedules and teamwork helped them win many games. They showed that the idea that Black athletes were not as good as white athletes was wrong. Besides winning games, the Tribune Girls also fought for equal chances in sports. They inspired other African American women to play sports professionally. The team also built strong ties with the community. They organized events and workshops to encourage young people to play basketball and live healthy lives. They are remembered not just for their championships, but also for helping to make sports more diverse and welcoming.

The Tribune Girls' success showed the cultural and social changes happening at the time. Their team existed during a bigger movement for African American women's rights. They helped challenge racial and gender barriers in sports. The Tribune Newsgirls were one of the first women's teams to get a lot of attention from a major African American newspaper. This helped them gain respect within the African American community and beyond. Also, the Tribune Girls' success on the court helped change how people saw African American women. It showed they could be excellent in competitive sports, which were often dominated by white athletes.

Coach Otto Briggs was a former player and organizer. He had strong connections in Philadelphia's African American community. He used his position at the Tribune to build a strong team and create chances for other African American women in sports. The team's success, especially in national championships, was a powerful message against the common racial stereotypes of the time. It proved that African American athletes, especially women, could achieve excellence at the highest levels.

Coach Otto Briggs' work with the Tribune Newsgirls was a natural fit for the newspaper's long history of supporting African American sports. As a key person in the team's rise, Briggs helped change how people viewed African American women in competitive sports. He challenged the idea that Black athletes were not as good as white athletes. Besides their sports achievements, the team's success showed how race and gender were connected. It proved that African American women could be excellent at the highest levels of competition. The Tribune Newsgirls were more than just a team; they helped bring about social change. Their success helped open doors for future generations of Black athletes to get recognition and opportunities in sports.

The Fight for Civil Rights

During the 1920s, John Asbury and Andrew Stevens became the first African Americans elected to the Pennsylvania State legislature. After this, the Tribune became even more active in city politics. In 1921, when the State legislature considered an Equal Rights Bill, the Tribune reported which representatives were against it. The newspaper strongly supported the bill until 1935, when Pennsylvania finally passed a state Equal Rights Bill.

Also in the 1920s and 1930s, the Tribune played a huge role in officially ending segregation in Philadelphia schools. The Tribune was upset that the Philadelphia School Board was not doing enough to end segregation. So, in 1926, it started the Defense Fund Committee. This committee raised money to support a court case against the school board. By 1932, the Tribune succeeded in getting African Americans appointed to the School Board. This eventually led to the end of segregation in Philadelphia's public schools.

Thanks to the Tribune's reporting and its partnership with the NAACP, Philadelphia gained national attention in 1965. This was when people protested to end segregation at Girard College. This school was set up to educate poor boys in the city, but historically, it had only allowed white students. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Philadelphia, which made the city and the Tribune's connection to the national civil rights movement even stronger.

See also

- List of newspapers in Pennsylvania

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |