Trapline facts for kids

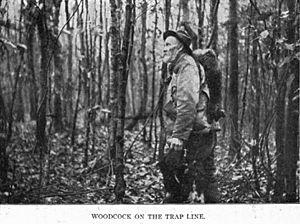

A trapline is a special path or route that a trapper uses. Along this path, the trapper sets traps to catch animals, usually for their fur. Trappers often follow the same route again and again. This helps them learn a lot about the wild areas they work in. They become experts in the local land and its features.

Because trappers know so much about their areas, their traplines are important. Not just for trappers, but also for people studying history, animals, or the land itself. In the past, groups of people decided together who could use which trapline areas. Sometimes, there were disagreements or even fights over these areas. Today, governments usually control and officially assign trapline areas. These official trapline boundaries are now used for many big land projects in places rich in fur animals.

Having a trapline area often means you can build a trapper's cabin there. This is a simple shelter where a trapper can stay while working on their trapline. Trappers' cabins are a well-known symbol in areas where fur trapping is common. They are an important part of the history and stories of places like Canada and Alaska, and for groups like the Métis.

How Indigenous Peoples Managed Trapping Long Ago

- Further information: Keyoh

Before Europeans came, Indigenous peoples had their own ways of managing land. They decided where families or groups could hunt, fish, and gather food. This was important to make sure they didn't take too many animals or plants from one area. Councils, which were like meetings, helped solve problems. Sometimes, conflicts could happen if rules were not followed.

When European traders started buying a lot of fur in the 1700s and 1800s, trapline areas became very valuable. This led to more disagreements over who owned which land.

Official Trapline Areas Today

In Canada, official trapping areas given out by the government are often called "registered traplines" (RTLs). Each province has its own system for managing them. These systems have been common across Canada since the 1930s.

In the province of Alberta, registered traplines used to follow specific natural features like a creek. But in the 1960s, they changed to a system of larger trapping territories.

In British Columbia, the registered trapline system is still the main way to manage fur-bearing animals. It helps decide how many animals can be caught. It is against the law to trap an animal on a registered trapline that isn't yours in British Columbia.

Manitoba has had registered traplines since 1940. They were started to stop too many new people from trapping in areas that already had too few animals. The system helps protect the local, mostly First Nations, population. The province's Wildlife Act manages this system. Traplines cannot be sold or passed down directly. Instead, they are given out using a points system. People who are close family members of the previous trapline holder, or who have used the trapline with permission, get special consideration. Living near the territory also helps.

As of 2013[update], Ontario has over 2,800 registered traplines on Crown land. Crown land is land owned by the government.

Since 2001, an agreement called the Paix des braves has been in place. This agreement uses trapline areas to help plan for forestry and mining projects. This happens in the Eeyou Istchee territory in Quebec.

Indigenous Land Rights

Indigenous peoples have not always agreed with how provincial governments control the fur industry. When the government assigns trapping areas, it suggests that the land belongs to the province. This can go against the idea that the land should be managed together, as agreed in some treaties. Also, having to ask the province for trapline assignments takes away control from local Indigenous leaders.

However, registered traplines also give Indigenous peoples legal rights to a piece of land outside their reserves. They can provide a way to earn a living and help people stay connected to their traditional way of life. Because of this, registered traplines are very important to many First Nations and Métis communities.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |