Vjekoslav Luburić facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vjekoslav Luburić

|

|

|---|---|

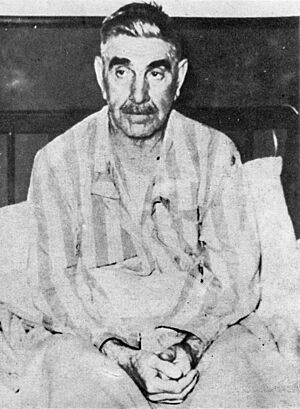

Luburić in the 1940s

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Maks |

| Born | 6 March 1914 Humac, Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 20 April 1969 (aged 55) Carcaixent, Spain |

| Allegiance | Independent State of Croatia |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1929–1945 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II in Yugoslavia |

| Spouse(s) |

Isabela Hernaiz

(m. 1953; div. 1957) |

| Children | 5 |

Vjekoslav Luburić (born March 6, 1914 – died April 20, 1969) was a Croatian official during World War II. He is called "one of the most notorious war criminals of the Second World War." Luburić was a leader in the Ustaše movement, which controlled the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). Luburić was in charge of the system of concentration camps in the NDH. He also oversaw the terrible killings of many Serbs, Jews, and Roma people in the NDH.

Luburić joined the Ustaše movement in 1931. He left Yugoslavia in 1932 and moved to Hungary. When the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia and the NDH was formed, Luburić returned. In 1941, he was sent to the Lika region. There, he oversaw mass killings of Serbs. These events led to the Srb uprising.

Luburić became the head of Bureau III. This part of the Ustaše Surveillance Service managed the NDH's concentration camps. The largest camp was Jasenovac. Around 100,000 people were killed there during the war. In 1942, Luburić was briefly a commander in the Croatian Home Guard. He was later put under house arrest but still controlled the camps.

In 1944, he helped stop a plan to overthrow the NDH leader, Ante Pavelić. In 1945, Luburić went to Sarajevo. For two months, he oversaw the torture and killing of many suspected communists. He was promoted to general in April 1945.

The NDH fell apart in May 1945. Luburić stayed behind to fight the communists. He was seriously injured. In 1949, he moved to Spain. He became active in groups of Ustaše who had also left Croatia. In 1955, Luburić disagreed with Pavelić about the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He then started his own Croatian nationalist group. Luburić was found murdered in his home in April 1969. It is believed he was killed by the Yugoslav secret police or rivals.

Contents

Early Life and Joining the Ustaše

Vjekoslav Luburić was born on March 6, 1914. His family was Herzegovinian Croat from the village of Humac. This was near Ljubuški. He was the third child of Ljubomir Luburić and Marija Soldo. His father was a bank clerk, and his mother was a homemaker.

In 1918, his father was killed. After this, Luburić grew to dislike Serbs and the Serbian monarchy. His sister Olga also died around this time. His mother then worked in a tobacco factory. She later remarried and had three more children.

Luburić finished primary school in Ljubuški. He then went to secondary school in Mostar. There, he started spending time with Croatian nationalist young people. He often skipped school and was aggressive. In 1929, he was arrested for being homeless. He was sentenced to two days in prison.

In 1931, Luburić dropped out of high school. He started working at the Mostar public stock exchange. The same year, he joined the Ustaše. This was a Croatian fascist group that wanted to destroy Yugoslavia. They aimed to create a "Greater Croatia." Luburić was arrested for stealing money from the exchange. He was sentenced to five months in prison.

He escaped but was caught near the Albanian border. After his release, Luburić moved to northern Croatia. He then secretly crossed into Hungary. He joined the Croatian exiles in Budapest. Then he went to an Ustaše training camp called Janka-Puszta. This camp was near the Yugoslav border. Hungary and Italy supported the Ustaše.

At Janka-Puszta, Luburić trained and made anti-Serb propaganda. He earned the nickname Maks there. He used this name for the rest of his life. In 1934, King Alexander I of Yugoslavia was killed. This was a plot by the Ustaše and another group. Most Ustaše in Hungary were then expelled. But Luburić and a few others stayed. He lived in Nagykanizsa for a short time. He had a son there.

World War II and the NDH

The Independent State of Croatia

After 1938, Yugoslavia was pressured by the Axis powers. In April 1939, Italy invaded Albania, creating another border with Yugoslavia. When World War II started, Yugoslavia stayed neutral. But by early 1941, it was surrounded by Axis countries. Adolf Hitler wanted Yugoslavia to join the Axis.

On March 25, 1941, Yugoslavia signed the Pact. Two days later, a group of Serbian officers overthrew the government. This angered Hitler, who ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941.

On April 10, the creation of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was announced. Ante Pavelić arrived in Zagreb on April 15. He declared himself the leader, or Poglavnik, of the NDH. He promised loyalty to the Axis. Many Croats welcomed the NDH. The Ustaše became a popular movement very quickly. The NDH was divided into German and Italian zones.

On April 17, the Ustaše passed a law. This law allowed them to set up concentration camps. It also allowed mass shootings. The Ustaše's main goal was to remove Serbs from the NDH. Serbs made up about 30% of the population. Ustaše leaders openly said they wanted to kill one-third of Serbs. They also wanted to expel one-third and force one-third to convert to Catholicism.

Managing Concentration Camps

In April 1941, Luburić illegally entered Yugoslavia. He arrived in Zagreb and joined the Ustaše ruling body.

The NDH had two main security agencies. The Ustaše Surveillance Service (UNS) was one of them. The UNS was divided into three bureaus. Bureau III, also called the Ustaše Defense, ran the NDH's concentration camps. There were about 30 camps in total. For most of the war, Luburić led Bureau III. He had planned to create these camps while he was in exile.

In May 1941, two sub-camps of Jasenovac were built. These were Krapje (Jasenovac I) and Bročice (Jasenovac II). They opened on August 23. On the same day, all camps in coastal areas were closed. In the early months of Jasenovac, Luburić usually got approval for mass killings. He was very loyal to Pavelić. This loyalty helped him become a trusted member of Pavelić's inner circle.

In late September 1941, Luburić went to Germany. He studied how Germans created and ran concentration camps. His visit lasted ten days. Later Ustaše camps were based on German camps like Oranienburg. The Ustaše copied German methods for prisoners. This included how prisoners arrived, were registered, housed, and forced to work.

The Jasenovac camp system was in a Serb-populated area. Luburić ordered all Serb villages nearby to be destroyed. Their people were sent to Krapje and Bročice. In November 1941, Krapje and Bročice were closed. Prisoners who could work were forced to build a third camp, Jasenovac III, known as the Brickyard. Of 3,000–4,000 prisoners, only 1,500 survived to reach the Brickyard.

Jasenovac Expansion and Control

With what he learned in Germany, Luburić made the Brickyard more efficient. In January 1942, Jasenovac IV was created for leather production. It was called the Tannery. A fifth camp, Jasenovac V, was also set up. This was Stara Gradiška. Both male and female guards worked there. Luburić's half-sisters, Nada and Zora, were among them. Luburić also recruited his cousin, Ljubo Miloš, who worked at the Brickyard. Most Ustaše running the Jasenovac camps were very young.

More than 1,500 Ustaše guarded the Jasenovac camps. The Brickyard, Tannery, and Stara Gradiška could hold 7,000 prisoners. Luburić visited the camps two or three times a month.

In early 1942, conditions at Jasenovac improved for a short time. This was because a Red Cross group was visiting. Healthy prisoners were given new beds and allowed to speak to the group. Sick prisoners were killed. After the Red Cross left, conditions returned to how they were before.

Luburić was not helpful to families asking about prisoners. He only allowed large deliveries of food and clothing, not individual ones. This way, he did not reveal who was still alive.

Kozara Offensive and Its Aftermath

On December 21, 1941, Ustaše units led by Luburić entered Prkosi. Luburić declared that everyone must be killed. The Ustaše rounded up over 400 Serb civilians. They were led to a forest and killed. On January 14, 1942, Luburić led Ustaše into Draksenić. More than 200 villagers were killed.

In June 1942, German, Home Guard, and Ustaše forces launched the Kozara Offensive. This was to remove Partisans from Mount Kozara. The Partisans were defeated. But the local civilians suffered greatly. Between June 10 and July 30, 1942, 60,000 civilians were rounded up. Most were Serbs. They were taken to concentration camps.

After Kozara, Luburić wanted to create a "tax." Serb boys would be taken from their families. They would be forced to give up their Serb identity and join the Ustaše. He "adopted" 450 boys displaced by the fighting. He called them his "little janissaries." They wore black Ustaše robes. They were forced to do military drills and pray. But most boys refused to become Ustaše. Many died from hunger and disease.

Hundreds of other children from Kozara were saved by Red Cross volunteers. They were led by Diana Budisavljević.

Later War Years

In August 1942, Luburić was promoted to Major. German officials complained that Luburić was causing problems. To calm the Germans, Pavelić sent Luburić to Travnik. He was made commander of the 9th Infantry Regiment. This unit was to secure the border with Italian-occupied Montenegro.

But Luburić shot and killed one of his soldiers. He was immediately removed from command. In November, Germans pushed for Luburić to be put under house arrest. He stayed in a Zagreb apartment with his mother and half-sisters. Other people took over his duties at Jasenovac. But Luburić still controlled the camp operations. For example, he arranged the release of Miroslav Filipović. Filipović had been jailed for terrible acts against Serbs. He was then made commander of Stara Gradiška.

By late 1942, unrest in the NDH hurt German interests. Germans wanted Pavelić to stop the Ustaše killings of Serbs. The Ustaše then created the "Croatian Orthodox Church." This was to make Serbs become "Croats of the Orthodox faith." Pavelić blamed others for the NDH's problems. In October 1942, two Ustaše leaders were exiled. In January 1943, the UNS was dissolved. A new agency took over the camps.

Luburić moved to a village near Lepoglava in mid-1943. He started planning guerrilla attacks against the Partisans. This was in case Germany lost the war. The number of Partisans grew greatly. In September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies. Partisans got many modern weapons from Italian units.

Luburić was mostly out of action in 1944. But his situation changed in August 1944. He helped stop the Lorković–Vokić plot. This was a plan by government ministers to overthrow Pavelić. Luburić oversaw their arrests. He also questioned them and other suspected plotters. In October, Luburić was promoted to Colonel.

Terror in Sarajevo

In early 1945, Pavelić sent Luburić to Sarajevo. His mission was to destroy the communist underground. Luburić arrived on February 15. Five days later, Hitler declared Sarajevo a "fortress." He wanted it defended at all costs.

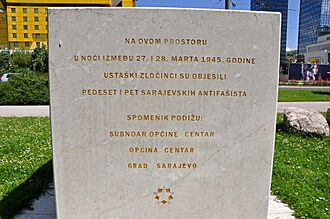

On February 24, Luburić announced he would destroy the communist resistance. He appointed nine Ustaše officers for executions. His headquarters was a villa in downtown Sarajevo. Locals called it the "house of terror."

On March 1, the Partisans began attacking Sarajevo. By early March, the city was surrounded. Luburić set up a special court. It dealt with cases of alleged treason and other charges. The first prisoners were 17 Muslim refugees. Over the month, dozens of suspected communists were executed. Arrests and executions were random, causing great fear. Some Sarajevans hid in bomb shelters, even without bombings.

On April 4, Luburić and his group left Sarajevo. About 350 Ustaše police and 400 soldiers stayed to defend the city. Luburić's time in Sarajevo led to 323 deaths. Hundreds more were sent to camps. The Partisans entered Sarajevo on April 6, liberating the city.

End of the NDH

After leaving Sarajevo, Luburić flew to Zagreb. His plane crashed while landing. Luburić was injured and hospitalized. Pavelić visited him. Luburić was disillusioned, blaming the Germans for betraying Croatia. Soon after, Luburić was promoted to General.

In early April, he ordered the remaining prisoners at Jasenovac to be killed. He also ordered camp documents to be destroyed. Several people with information about Luburić's wartime actions were killed.

As the Partisans approached, Luburić suggested a last stand in Zagreb. But Pavelić refused. Some Ustaše wanted to retreat to Austria. Others, like Luburić, wanted to form guerrilla groups.

In early May, Luburić met with the Archbishop of Zagreb. The Archbishop urged him not to fight the Partisans. On May 5, the NDH government left Zagreb, followed by Pavelić. By May 15, the NDH had completely fallen. Tens of thousands of Ustaše surrendered to the British Army. But they were handed back to the Partisans. Many were killed in revenge killings.

Some Ustaše, called Crusaders, stayed in Yugoslavia. They carried out guerrilla attacks. Luburić led a small group in Slovenia and Slavonia. He avoided capture by putting his papers on a dead soldier. He sent a letter to Pavelić, who had escaped to Austria. Luburić said he would keep fighting.

There are different stories about Luburić's actions after the war. One says he went south and then west. He then escaped to Hungary in November 1945. Another says he was wounded in a gunfight. He was carried to Hungary and then left the country. Luburić himself claimed he fought until late 1947. He was seriously wounded and forced to leave.

Luburić's half-sister Nada and her husband Dinko Šakić escaped to Argentina. But other relatives were not as lucky. Miloš was caught in July 1947. He was put on trial for his role in the killings at Jasenovac. He confessed in detail. He was found responsible and executed in 1948.

Later Life in Exile

Life in Spain

In 1949, Luburić moved to Spain. Spain was a good place for Ustaše exiles. It was the only country outside the Axis that recognized the NDH. Luburić entered Spain using the name Maximilian Soldo. He was briefly imprisoned but then released. With help from a former general, he settled in Benigànim.

Pavelić had settled in Argentina. He became the unofficial leader of Croatian exiles in South America.

In 1951, Luburić set up a recruiting center in Hamburg for Pavelić's group. That same year, he started a newspaper called Drina. In November 1953, Luburić married Isabela Hernaiz, a Spanish woman. They had four children.

Disagreement with Pavelić

In 1955, Pavelić discussed dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina with Chetnik exiles. This angered Luburić. He believed Croatia should extend to the Drina River. He also thought it should include parts of Serbia. Luburić strongly criticized Pavelić. He then founded the Friends of the Drina Society and the Croatian National Resistance (HNO). In June 1956, Pavelić started a rival group.

In 1957, Luburić's wife received a letter. It detailed her husband's wartime actions, especially the killing of children. She filed for divorce. Luburić was given joint custody of their children and their home. He sold the home and moved to Carcaixent. He opened a poultry farm, but it failed. He then became a traveling salesman.

In Carcaixent, he started a small publishing house called Drina Press. His neighbors knew him as Vicente Pérez García. They did not know about his past. He wrote articles using pseudonyms like General Drinjanin. In his writings, Luburić admitted to some mistakes during the war. But he never expressed regret for the terrible acts he was accused of. He called for "national reconciliation" between Croats. He also claimed to have contacted the Soviet Union's intelligence services. He argued that Croatia should be neutral if Yugoslavia broke apart. This idea was not popular with some anti-communist Croats.

On April 10, 1957, Pavelić was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt. This was by the Yugoslav secret service. He died in December 1959. Because of their disagreement, Luburić was not allowed to attend Pavelić's funeral. After Pavelić's death, Luburić tried to take control of Pavelić's group. He said he was the last commander of the Croatian Armed Forces. But the group's leaders refused him. Luburić then became more focused on military training. He set up neo-Ustaše training camps in Europe. He also published articles on military tactics. In 1963, he started a paper called Obrana ("Defense").

Death and assessment

On the morning of April 21, 1969, Luburić's teenage son found his father dead. Luburić had been killed the day before.

After Luburić's death, the leadership of the HNO split. It divided into groups in different countries.

German records from the time say the Ustaše killed about 350,000 Serbs. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates 320,000 to 340,000 Serbs were killed by the Ustaše. Most modern historians agree over 300,000 Serbs were killed. This was about 17 percent of all Serbs in the NDH. At the Nuremberg trials, these killings were called genocide. The Ustaše also caused the deaths of 26,000 Jews and 20,000 Roma.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |