Walls of Cuéllar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Walled enclosureand castle of Cuéllar |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| General information | |

| Type | Monument |

| Architectural style | Romanesque, Mudéjar, Gothic |

| Location | |

| Town or city | |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 41°24′N 4°19′W / 41.4°N 4.32°W |

| Construction started | 11th Century |

| Construction stopped | 15th Century |

The Walls of Cuéllar are ancient stone walls that surround the old town of Cuéllar in Segovia, Spain. These walls are some of the most important and best-preserved old defenses in the region of Castile and León.

The walls are made up of three main parts: the city wall, the castle area (called the citadel), and an outer protective wall. There's also evidence of a fourth wall that has disappeared over time. The first parts of the walls were built in the 11th century. They were made even stronger in the 15th century by Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, who was the Duke and lord of Cuéllar.

Originally, the walls stretched for more than 2,000 meters (2 kilometers). Today, about 1,400 meters of them still stand. They are about one and a half meters thick and more than five meters tall. Seven of the original eleven gates, which allowed people to enter different parts of the town, are still there. One famous gate is the Arch of San Basilio, built in the beautiful Mudéjar style.

After the 17th century, the walls were no longer needed for defense. People started to care less about keeping them in good shape. By the 19th century, some of the most damaged parts were even torn down. This, along with general wear and tear, caused about a quarter of the walls to be lost. In the 1970s, people began to restore different sections to stop them from falling apart.

The most recent big restoration finished in 2011. It was funded by the Spanish government with 3.4 million euros from European money. This project helped make the walls a popular tourist attraction, allowing visitors to walk along some parts of them.

The Cuéllar walls look a lot like the military buildings in Toledo from the 14th century. In 1931, the walls and Cuéllar Castle were declared a national artistic monument. This special recognition is known as a Bien de Interés Cultural.

Contents

History of the Walls

Building the Walls: 10th to 15th Centuries

Walls were super important for medieval towns. They protected people and helped a town grow. This was especially true for towns like Cuéllar, which was on a border near the Douro River. Cuéllar was built on small hills for better defense. The wall followed the shape of these hills, making the highest part of the town a fortress.

The Walls of Cuéllar began in the Early Middle Ages. This was when King Alfonso VI asked Count Pedro Ansúrez to repopulate the town. Building started around 1085. The oldest parts of the wall, found near the castle, date back to the 11th century. More sections were added throughout the 12th and 13th centuries.

The first written record of the walls is from April 29, 1264. In this document, King Alfonso X the Wise allowed Cuéllar's town council to use money from certain fines to fix the walls. He knew the walls and bridges were important for the town's safety.

Later, in 1374, the town council asked King Henry II for money to repair the walls, but he didn't agree. In 1403, the town council asked Prince Ferdinand for help. He gave them permission to collect 30,000 maravedís from everyone in Cuéllar, rich or poor, to fix the walls. This shows how much the town cared about its defenses.

In 1427, John II of Aragon, who was the lord of Cuéllar, allowed Archdeacon Gómez González to build the Hospital de la Magdalena next to the wall. The town council was worried this would weaken the defenses. The archdeacon was supposed to leave a walkway for soldiers on the wall, but he built the hospital right on top of it.

Changes in the 16th Century

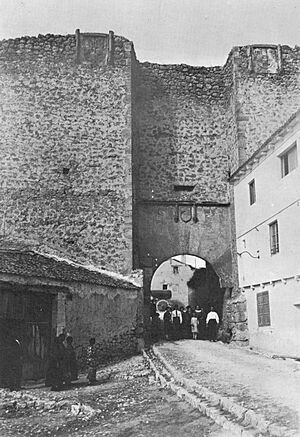

The walls were rebuilt and made bigger in the 14th and 15th centuries for defense. When Beltrán de la Cueva became lord of Cuéllar in 1464, the old Romanesque walls were in good shape. As he made the castle bigger, he also strengthened the rest of the town's defenses. In 1471, he made the north wall taller and added a protective outer wall. He also reinforced the first wall section from the Arch of San Basilio to the castle.

Around this time, the Catholic Monarchs (King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella) started a program to check and repair walls in Castilian cities. They asked lords and officials to report on the walls' condition and how much it would cost to fix them. So, the work done by the first duke might have been part of this larger effort.

After Beltrán's death in 1492, his son, Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, continued the work. He was the 2nd Duke of Alburquerque and lord of Cuéllar. The most important changes happened around 1500. The duke wanted to strengthen the walls to protect his rights over the town from his stepmother. He paid half the cost, which was unusual, as usually the townspeople paid for such repairs.

The 2nd Duke started by strengthening the first wall section, from the Church of San Esteban to the Arch of San Martín, and then to the Arch of Santiago. He made the walls taller and added battlements (the tooth-like tops) with arrowslits (narrow openings for archers). He also worked on the Arch of San Pedro, making its church look like a military building. He placed his family's coat of arms on all the gates he reinforced.

Walls Abandoned: 17th to 19th Centuries

From the 17th century onwards, the walls were no longer the main defense. People started to ignore them, and they slowly began to fall apart. Many buildings were built right against the walls. For example, in 1587, someone was allowed to build a house next to the Walls of San Pedro. In the mid-17th century, another house was built near the Arch of San Martín. These new buildings often used the wall as a support, which damaged it. People also opened windows and other spaces in the wall, weakening it further.

In the mid-17th century, some people even took stones from the wall to build their own houses. The town council tried to stop this with lawsuits and fines. In the 18th century, the outer part of the Puerta de Carchena had to be torn down. The Arch of La Trinidad was also in danger of collapsing in 1777.

The walls used to belong to the Duke of Alburquerque. But in 1811, the system of lordships (where nobles owned towns) was ended. The 14th Duke died without a direct heir, ending his family line in the duchy. After a long legal fight, the Alburquerque title went to the Osorio family.

The new Duke, Nicolás Osorio y Zayas, didn't care much about Cuéllar. This led to the worst period of damage for the walls. In 1842, a wall section near the Grammar School was about to fall. The town council told the Duke, but he refused to fix it. That same year, the doors of the Arches of San Andrés and Carchena were removed to prevent them from causing the arches to collapse. Later, the doors of the Arch of La Trinidad were also removed.

In 1858 and 1859, more parts of the wall collapsed near the Arch of Santiago. This worried the town leaders. They wondered who owned the walls. Lawyers said that since the lordships were gone, the Duke no longer owned them. So, the Duke had to give up his rights, and the town council became the owner of the walls.

After this, authorities sent an expert to check the walls. He found four dangerous areas. The town council told people living in houses attached to these parts to move out. In 1868, it was decided that the dangerous sections of the wall should be torn down. This demolition happened over several years. In 1873, a section of wall near the Arch of La Trinidad collapsed, and its remaining battlements disappeared.

Demolition in the 20th Century

Even though the town council now owned the walls, they didn't have enough money to fix them. It was cheaper to tear down dangerous parts than to restore them. So, demolitions continued into the early 20th century.

In 1873, the Arch of Carchena was torn down. A year later, part of the wall on Barrera and Herreros streets collapsed. In 1878, a huge section of wall in that area disappeared. Reports pointed out more dangerous spots. In 1879, the demolition of the Herreros Street wall began. The town council also decided to tear down the Arch and wall of Trinidad. In 1884, the Arch of Carchena was completely removed, as was one of the arches of San Andrés. In 1895, the Arch of San Pedro was demolished. This not only made the area safer but also widened the street. The Arch of Las Cuevas was likely demolished around this time too, though the exact date isn't recorded.

In the early 20th century, the walls continued to lose stability. Between 1923 and 1932, the town council started to spend small amounts of money on restoration. This continued after the walls were declared a Historic-Artistic Grouping in 1931.

In the 1940s, when the castle was a prison, prisoners lowered the height of the wall on the north side of the castle by two meters. The stones were used to build a sanatorium (a hospital for people with tuberculosis) south of the castle.

In 1955, a large section of the wall between the Arch of San Basilio and the castle was torn down. This was done to create a wider entrance to Palace Street. Many people in the town were very upset. They felt it was a destruction of history. The town council said it was just enlarging a small existing passage. However, photos show a very narrow passage before, nothing like the eight-meter wide opening created. Thousands of cubic meters of earth had to be moved.

People soon realized why the new entrance was made. It allowed large trucks to enter and exit the castle area, where the acting mayor owned a chicory factory. The Arch of San Basilio was too small for big trucks. The new entrance made it easier for the factory to load and unload goods.

On December 14, 1960, the town council allowed another wall section to be torn down in the lower part of town. This section closed the city enclosure with the disappeared Arch of San Pedro. The demolition also included an old manor house, believed to be the birthplace of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the first governor of Cuba.

Attempts to Recover the Walls: 20th Century

In the 1970s, people started to realize the historical importance of the walls again. Small restoration projects began. In 1972, a bank and the Provincial Council of Segovia donated money to restore the Arch of San Basilio.

On February 4, 1977, part of the tower of the Arch of Santiago collapsed. It was quickly restored, but its height was greatly reduced. At the same time, the town council bought houses built against the wall on Muralla Street and near the Arch of San Martín. They tore these houses down to show the wall sections behind them. The Ministry of Culture also restored the Arch of San Andrés and the wall section connecting the Arch of San Martín with the Arch of Santiago. In 1986, the town council bought another building next to the wall to free up more sections.

Between 1988 and 1989, the town council repaired the southern wall of the Huerta del Duque. This part had large holes and was in danger of collapsing. They used 630 cubic meters of stone for the repair. During this work, a hidden Mudéjar postern (a small, secret gate) was discovered.

On November 2, 1998, during work in the Plaza de San Gil, a section of wall (11 meters long, 4.5 meters high, 2.20 meters wide) was illegally torn down. It was claimed to be an accident, but investigations showed it was done on purpose. The regional government fined the town council 8 million pesetas.

Even though the restoration was approved, the wall section was not rebuilt. Instead, it was turned into a lookout point. The height of another wall section was also reduced, removing more stone.

In 2002, a major restoration of the Walls of Cuéllar on Nueva Street, where the Hospital de la Magdalena is located, was carried out. This was a joint effort between the town council and national and European organizations.

21st Century: Complete Restoration

In 2000, plans began for a big restoration project. It was funded by the Spanish government and European funds. The project aimed to carefully study and restore different parts of the walls.

The restoration work started in April 2008, with a budget of about 3.4 million euros. It continued through 2009, 2010, and 2011. This project allowed for a complete and organized restoration of the walls.

Most of the walls were rebuilt, bringing back the walkway for soldiers and the battlements. New entrances were added, and parts of the citadel wall were made accessible to the public for tourism. Excavations were done in the castle moat to find its original levels. The citadel wall was also closed at its ends, and the wall of the Plaza de San Gil was rebuilt. The outside of the castle's west side was also restored, and the Hospital de la Magdalena was turned into a youth hostel.

To restore some sections, the town council bought land and buildings attached to the wall. This freed up the wall and allowed for better views. The goal was to keep the original look of the walls as much as possible, to restore their defensive features, and to make them enjoyable for visitors.

The work finished in the summer of 2011, costing over 3.5 million euros. It was fully paid for by the Spanish Ministry of Development. The restored walls were opened to the public on November 22, 2011. In less than two months, more than 5,000 people visited them.

What the Walls Look Like

Today, the walls stretch for over 1,400 meters. This is about three-quarters of their original length of more than 2,000 meters. They enclose an area of about 14 hectares (about 35 acres). The walls fit perfectly with the castle, which is the main defense of the town.

The wall has two main parts: the citadel (castle area) and the city wall. They are about 1.5 meters thick and over 5 meters tall. The walls form a shape like an ellipse. At each end, the castle to the west and the Church of San Pedro to the east, strengthen the defenses. The Church of San Pedro's back part sticks out from the wall, like a fortress.

The walls are mostly built from lime and rough stones. Some parts show Mudéjar influences, like the tower of the Arch of Las Cuevas, the Arch of San Andrés, the Tower of the Daza family, the Arch of San Basilio, and the south gate of the castle. The stones are irregularly shaped and held together with lime mortar. Today, only some sections of the wall still have their battlements. Most of the chemin de ronde (the walkway for soldiers) has been lost. There are also remains of arrowslits and machicolations (openings for dropping things on attackers), especially near the Arch of San Martín. We don't know what the original Arches of Las Cuevas, La Trinidad, and Carchena looked like.

The citadel seems to follow the path of ancient Celtiberian forts. It also looks like Muslim citadels. In Cuéllar, like in other old cities, churches were part of the defenses. The Churches of San Esteban and Santiago were part of the citadel, and San Pedro was part of the city wall.

Citadel Wall

The first walled area, called the citadel, is on the highest part of the hill where Cuéllar stands. It's separate from the rest of the town. This was the first part of the town to be walled, and it later expanded downhill as the town grew. It covers about two-fifths of the total walled area. It's higher up, close to the castle, and has fewer buildings, partly because of the large open space in front of the castle.

The citadel wall started from the castle itself. It crossed the Huerta del Duque with a long wall that is missing its battlements. This wall ends in a square tower with Mudéjar decoration. This tower was part of the defense for the disappeared Arch of Las Cuevas. It's possible another gate was here, leading into the city.

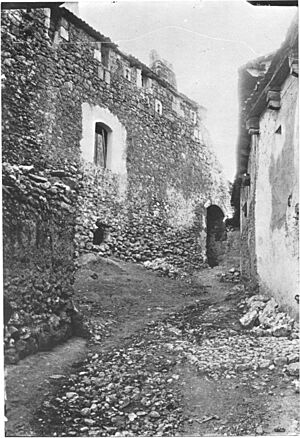

From Las Cuevas street, the wall continued to the Arch of Santiago. Its tower was also the bell tower of the nearby church. From this point, one of the strongest sections of the wall began. It still has some battlements and an intermediate square tower in perfect condition. This section ended at the very strong Arch of San Martín. The wall then turned, going behind the Church of San Esteban. The church's apse (rounded end) was used as a strong point, sticking out from the wall. The wall then closed behind the Grammar School. The section of wall between the School and the Judería gate is one of the best preserved. From the Judería, the wall went back towards the castle. It was strengthened by another tower, now called Torreón de los Daza. The wall reached the Arch of San Basilio through a section that has mostly disappeared today. From there, another wall, demolished in 1955 for a street, ended at the castle.

The citadel was very hard to attack. There were also outer defenses guarding the valley. Inside the citadel, there were five gates to enter from different parts of the town. Only four of these gates remain, as the Arch of Las Cuevas has disappeared. The Churches of San Esteban and Santiago also acted as strong points to protect this first walled area.

Gates of the Citadel

This area had five gates that connected the citadel with the rest of the city.

- Arch of San Basilio: First called Puerta del Robledo, it got its current name in the 17th century from a nearby monastery. It's the direct entrance to the citadel from the northwest. It's like a small fortress with a round tower and a rectangular keep (main tower). Between them is the soldiers' walkway over a triple arch. It's built with stone and brick, with Mudéjar designs. The gate has three coats of arms: the Cueva and Toledo families on the sides, and Cuéllar's council in the middle.

- Puerta de la Judería: Named because it was in the Jewish quarter. It's the smallest gate and connected the two walled areas. Unlike the other gates, it doesn't have towers. It's simply a passage dug directly into the wall.

- Arch of San Martín: Located to the east, it was already called this in 1437. The gate has two rectangular towers with the shields of the House of Alburquerque (Cueva and Toledo families). The town council's coat of arms is above the door.

- Arch of Santiago: Named after the nearby church. It's one of the smallest gates, meant for people walking, not enemy cavalry. Its defensive tower was also the church's bell tower. The church's apse helped defend the arch. It collapsed in 1977 and was rebuilt, but it lost much of its height.

- Arch of Las Cuevas: We don't know its original design, but a preserved square tower with Mudéjar decoration suggests it had this style. It was already in ruins in 1858 and was likely torn down around 1895.

Also, inside the citadel is the Portillo del Castillo. This small gate has Mudéjar decorations. It's located between the castle and the Arch of Las Cuevas. After the 2011 restoration, it now has stairs connecting 'La Huerta del Duque' and 'La Esplanada del Castillo'. It was originally a gate for riders, connecting to the outer slope.

The Castle

The castle is built on the southeast corner of the wall. Its Mudéjar gate is an old part of the walls, similar to the Puerta de San Basilio but larger. This gate, now called a tower-gate, has two slightly turned side towers. These towers were designed to make projectiles bounce off, preventing a direct hit. It has a small entrance area with remains of a double armored door, a portcullis (a heavy grating that slides down), and an embrasure (an opening for shooting). Inside the castle, there are also remains of a Mudéjar cistern (a water tank). This cistern would have supplied water to the guard posts. There's also a Mudéjar gallery, which was a staircase to one of the wall's towers. When the castle was built, this staircase became part of the fortress.

Church of San Esteban

This church is just outside the citadel walls. The wall makes a sharp turn in front of it. The church's tall tower, made of lime and stone, was mainly meant to protect the wall from attacks. Thick walls surround the church, making it look like a fortified area. What seems to be the church's cemetery actually has large, well-cut stones at its base. These are probably the only Roman remains in Cuéllar. It might have been an older fortification, later used to defend the church and as a cemetery.

Church of Santiago

The Church of Santiago, with its Mudéjar apse and parts of its walls still standing, was very important. It was where the nobles of Cuéllar met. It also housed the House of Lineages (a noble institution). It stood at the top of the citadel wall, also outside the main citadel. Its tower provided extra defense in a vulnerable area. It was attached to the wall, strengthening the nearby tower of the Arch of Santiago.

City Wall

Not many parts of the outer city wall remain today. It started from the citadel wall, near the Arch of Las Cuevas. You can still see a very low part of this starting wall. It then went towards the Convent of La Trinidad, where the base of a strong tower still stands. The wall continued, turning south to meet the disappeared Arch of La Trinidad, after passing the Portillo de Santa Marina.

From the Arch of La Trinidad, the wall is mostly hidden by modern buildings. But its path went straight to the Church of San Pedro. It was attached to the back of the church, turning the church into a fortress. This defended the now-disappeared Puerta de San Pedro, which was in a very exposed part of town.

The wall continues along the street named after it, up to the disappeared Puerta de Carchena. This was also a large fortified area. From there, the wall crossed the Palace of Santa Cruz, reappearing on its back side as the base of a wooden gallery of the palace. It then continued north to the Hospital de la Magdalena and ended at the Arch of San Andrés. After this arch, the wall went back to join the citadel wall, near the Puerta de la Judería. This outer wall protected the main square and the heart of the old city.

Gates of the City

The city wall had four main gates. Only one, the Arch of San Andrés, remains. The gates were placed where the main roads crossed Cuéllar.

- Arch of San Andrés: Located on the north side, it's one of the most elegant gates. It has Mudéjar remains and large, carved stones framing the town council's coat of arms. You can still see the hinges that held its large doors.

- Arch of Carchena: Located on the northwest side, it connected the Franciscan convent area with the town's administrative center. It was later called "Arch of San Francisco" because it was near that monastery. It was ordered to be torn down in 1873 because it was in ruins. We don't have pictures of its original shape, but part of what might have been its defensive tower remains.

- Arch of San Pedro: Located on the southeast side, next to the church of the same name. It was the town's main gate. Important public events, like changes in town ownership, happened here. It was torn down in 1895. There were rooms and houses built on top of it.

- Arch of La Trinidad: It was in the southern corner. It allowed access to the area around the Church of El Salvador. Its shape is unknown, as it was torn down between 1879 and 1880 due to its ruined state. It's named after the nearby Convent of La Trinidad. You can still see the start of the arch on a modern building's facade.

Within this area is another gate, the Portillo de Santa Marina. It's in the Mudéjar style. It connected the old butcher shops with the orchards near the Convent of La Trinidad. This area was known as Dexángel, meaning "drainage," because waste from the butcher shops flowed under the wall here. It was likely a gate used for surveillance.

Church of San Pedro

Located in the southern part of the wall, this church protected the most vulnerable point. So, it looks like both a religious building and a fortress. It completed the wall with a stone apse (rounded end) reinforced with cross-shaped arrowslits and machicolations. These were openings for dropping things on attackers. This part was built by Francisco Fernandez de la Cueva in the 16th century. Above the protective wall is his coat of arms.

Next to its arch, attached to the apse, the church became a small fortress. This gave more security to the southern part of the wall, which faced a wide, open plain and was therefore a risky area.

Counter Wall

The counter wall, or outer defense, was a third layer of protection. It surrounded the two main walls but is now quite damaged. It acted like a barbican (an outer defense) in front of parts of the citadel wall and the entire city wall.

You can still see parts of it in front of the citadel walls as they pass through the Huerta del Duque. It's also clearly visible in front of the city walls near the Convent of La Trinidad. Here, some well-preserved parts of this outer wall still have battlements. It continued to the Arch of La Trinidad, sometimes splitting into sections. It reappears near the Church of San Pedro, behind modern buildings, with some crenellated (battlemented) sections. Past the Arch of San Pedro, it runs parallel to Las Parras Street. Here, houses are built against it, except for the last ones, where the counter wall was torn down a decade ago. Remains appear again in Nueva Street, continuing up to the Arch of San Andrés. From there, it followed La Barrera street (named after this outer wall), running parallel to the main wall up to the Arch of San Basilio. On the other other side, towards the castle, it reappears up to the large Santo Domingo cube, which belongs to the fortress.

Lost Wall Section

Recent studies show there was a fourth wall section that has now disappeared. It started from the castle and connected to the Arch of San Basilio with towers. Another wall came from this arch and reached a complex tower, which might have later become the tower of the Church of San Martín. Through a gate, this wall continued until it joined the citadel. This fourth wall would have made the castle even stronger and harder to reach.

What the Walls Were Used For

The walls weren't just for defense. They also played a role in trade and the economy. Most importantly, they looked impressive, showing the city's power. The medieval wall also separated the city from the countryside. Living inside the walls meant you were a "Villager Knight," different from peasants or foreigners outside.

Over time, their military use became less important. Their commercial value grew instead. The walls acted like a customs office, controlling who entered the city and making sure people paid taxes. These taxes included the "portazgo" (for passing through a gate), the "alcabala" (a sales tax), and the "cornado de la cerca" (a special tax in Castile for wall construction).

The walls also served as a health barrier. They helped isolate towns from the plagues and epidemics common in the Middle Ages. Rules also made sure people threw their waste outside the walls, keeping the inside cleaner.

People in those times saw cities through their walls. A city, protected by its fortified walls, looked powerful and stood out. This is how Cuéllar appeared to visitors: a strong city that ruled over a large area around it.

Watching and Keeping the Walls Safe

Money for building or fixing walls usually came from "repartimientos." These were taxes shared among everyone in the town and its surrounding lands, including common people, Jews, Muslims, clergy, and nobles.

The gates of the citadel and city walls had large, locked doors. Once closed, no one could enter or leave. In the late 16th century, money was paid for new locks on the gates of La Trinidad, Carchena, and San Basilio. In 1551, certain people were assigned to guard specific gates on certain days. In 1564, gatekeepers were paid for their work.

It seems that nobles were in charge of guarding the gates. The internal structure of the House of Lineages, a noble institution, supports this. It was divided into "Upper" and "Lower" parties, reflecting the town's two halves: the citadel and the city. These parties had smaller divisions called adras and quarters. Quarters were not just areas but also referred to military guard shifts. This military system was set up in the 14th century and lasted until the early 17th century. Its disappearance seems to match the time when the walls stopped being mainly for defense and became more about controlling access and collecting taxes.

See also

In Spanish: Muralla de Cuéllar para niños

In Spanish: Muralla de Cuéllar para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |