Wheal Metal facts for kids

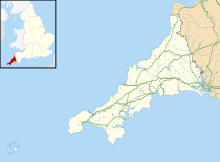

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Helston |

| County | Cornwall |

| Country | UK |

| Coordinates | 50°07′16″N 5°19′00″W / 50.121138°N 5.316675°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Tin |

| History | |

| Opened | 15th century |

| Closed | c. 1877 |

Wheal Metal was a famous tin mine in west Cornwall, England. Even though it wasn't as well-known as its neighbor, Wheal Vor, people in 1885 called it "probably the richest tin mine in the world." Today, you can still see a very impressive engine house from the mid-1800s at Wheal Metal. This engine house is important because it's the only large building left from a group of mines that produced more than a quarter of all the tin in Cornwall during that time.

Contents

How the Tin Formed Underground

About 290 to 280 million years ago, huge blobs of hot rock, called granite, pushed up into the older rocks (called killas) in this area. As these granite blobs cooled down, cracks formed in them and in the surrounding killas. These cracks became pathways for hot, mineral-rich water to flow through. This water left behind valuable minerals, forming what miners call "lodes." These lodes are like veins of minerals, varying from a few inches to several feet thick.

Wheal Metal is located where two of these granite hills, Tregonning Hill and Godolphin Hill, meet. When the lodes reached the surface, the minerals were washed away by streams. This gave early miners an easy way to find and collect the minerals, especially tin, which gathered in places called "placers." Wheal Metal mainly produced tin, with a small amount of arsenic, but very little copper.

Early Days of Mining

Wheal Metal is located on the side of a valley with a stream called Sithney waters. We don't have many old records, but it's very likely that people started mining here a long time ago. The two main mineral lodes cross the stream, making it easy to dig into the hillsides to find them.

It's also possible that early miners used water power to help them. There's a filled-in shaft near the stream, and signs of old pools and a sluice gate upstream. This suggests they used the stream's power, perhaps for pumps. The area is known as Poldown, and "Pol" in Cornish names often means "pool."

Mining in the 1800s

Wheal Metal's history in the 1800s is closely connected to the nearby Wheal Vor mine and the price of tin. When tin prices went up, like in 1811, 1857, and 1872, there was more mining activity at Wheal Metal. The same people who worked at Wheal Vor often worked at Wheal Metal too.

In the early 1800s, miners dug a shaft and put a small engine there. Over time, four main shafts were dug: Metal shaft, Old (or West) Metal shaft, Edwards shaft, and Iveys's shaft. By 1848, when work stopped at Wheal Vor, one of its engines was moved to Old Metal shaft. This shaft went down about 50 to 70 fathoms (a fathom is about 6 feet) below the main drainage tunnel, which is called an adit. Even though this wasn't as deep as Wheal Vor, it still produced good amounts of tin.

A New Company and Deeper Mining

As tin prices rose again, a new company called Great Wheal Vor United was formed in 1853. This company bought Wheal Metal and continued to dig deeper into its lodes, finding rich tin deposits at 80 fathoms. They might have also started working on a second lode called Schneider's lode.

In 1855, a 26-inch engine was installed at Wheal Metal. For a while, Wheal Metal and a nearby mine called Flow were the only sources of income for the company, which was spending a lot of money trying to drain water from Wheal Vor. By late 1857, Wheal Vor was drained, but the expected riches weren't found. However, Wheal Metal was doing well, so shareholders decided to keep going.

Moving the Giant Engine

In 1859, a larger 60-inch engine was installed at Iveys' shaft to help the mine go even deeper. By 1860, hopes for Wheal Vor were gone, and its engines were put up for sale. Since no one bought them, it was decided to move the huge 85-inch pumping engine and a steam engine from Wheal Vor to Iveys' shaft at Wheal Metal.

To avoid stopping the tin production, they built the new engine house for the 85-inch engine at a right angle to the 60-inch engine. The stones from the old engine house at Wheal Vor were carefully numbered, taken apart, and then used to build the new engine house at Wheal Metal. In 1864, the 85-inch engine was moved. This was a huge task, needing as many as 40 horses to pull the heavy parts! Once it was set up, the pumping rods were switched from the 60-inch engine to the 85-inch engine in just four days, with very little interruption to the mining.

By 1865, people were amazed, calling Wheal Metal "probably the richest tin mine in the world." In 1868, Iveys' shaft got a "man-engine," which was a special lift to help miners go up and down the shaft. Wheal Metal was producing a lot of tin, sometimes 60 to 80 tons of "black tin" (concentrated tin ore) per month in the mid-1860s. This was about 10 percent of all the tin produced in Cornwall that year!

Sometimes the mine would become less profitable and almost close, but then new discoveries would bring it back to life. However, by 1874, Iveys' shaft reached its deepest point of 227 fathoms. With less tin being found and tin prices falling, work finally stopped for good. In 1877, the company closed down, and the big 85-inch engine was sold and moved to a waterworks in Northumberland, where it stayed until the 1940s.

Wheal Metal Today

Today, the area where Wheal Metal once operated is made up of several private properties, connected by paths and lanes. The most striking thing you can see is the amazing engine house, which is in excellent condition. You can also spot a large cast-iron pipe near the engine house, which points to where the "dressing floor" (where tin ore was processed) might have been. There used to be a huge pile of waste rock nearby, but it was sold to the Navy to help build a runway at the nearby Culdrose Navy base.

Wheal Metal is part of a special area recognized as a World Heritage Site. This means it's important globally because of how much Cornish mining contributed to the Industrial Revolution. Because of this, the remaining buildings and landscapes are now seen as very important historical sites. Wheal Metal is considered a significant historical asset because its engine house is the only surviving structure from the Wheal Vor group of mines, which were so important for tin mining in Cornwall in the mid-1800s.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |