William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Bonville

|

|

|---|---|

| 1st Baron Bonville | |

Bonville's family coat of arms

|

|

| Successor | Cecily Bonville |

| Born | 12 or 31 August 1392 Shute Manor, Shute, Devon |

| Died | 18 February 1461 (aged 68) Following the Second Battle of St Albans |

| Noble family | Bonville |

| Spouses | Margaret Grey Elizabeth Courtenay |

| Issue Detail |

|

| Father | Sir John Bonville |

| Mother | Elizabeth Fitzroger |

William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville (born in 1392 and died in 1461), was a powerful English nobleman. He owned a lot of land in southwest England during the 1400s. His father died when William was young. So, he was raised by his grandfather, who was also an important person in Devon. Both his father and grandfather were good at politics and getting land. When William became an adult, he took control of a very large estate. He even gained more land by winning legal cases against his stepfather.

William served the King, which meant fighting in France during the Hundred Years' War. In 1415, he joined the English army invading France. He fought alongside the King's brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, in the Agincourt battle. William went on more missions in France throughout his life. But soon, problems in England, especially a big fight with his powerful neighbor, Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon, took up most of his time.

In 1437, King Henry VI gave Bonville an important job: manager of the Duchy of Cornwall. This job usually belonged to the Earls of Devon, and Courtenay was very angry about losing it. Their disagreement quickly turned violent. Bonville and Courtenay attacked each other's properties. The situation got worse in 1442 when the King gave Courtenay a similar job. The fight between them continued for the next ten years. King Henry and his government often failed to stop them. Sometimes, their efforts did not work. Once, Bonville was sent to France to get him out of the region. But the mission did not have enough money and failed. When Bonville returned, the fight started again. In 1453, King Henry became very ill for 18 months. This made the political problems in his kingdom even worse.

Bonville usually stayed loyal to the King. However, his main goal was to support anyone who would help him against Courtenay. Their feud was part of a larger breakdown of law and order. This eventually led to the Wars of the Roses in 1455. Bonville seemed to avoid getting caught in the changing political tides until 1460. At that point, he joined the rebellious Richard, Duke of York. This new alliance did not help him much. His son was killed with York at the Battle of Wakefield in December 1460. Bonville himself fought on the losing side at the Second Battle of St Albans two months later. With the new Earl of Devon watching, Bonville was executed on February 18, 1461.

Contents

Bonville's Early Life and Family

The Bonvilles were a major noble family in Devon in the late 1300s. They often worked closely with their neighbors, especially the Courtenay family, who were the Earls of Devon. A historian said that the Bonvilles were "super-knights." This means they were very important and powerful. They did not need to be afraid of the great lords because they were great themselves.

William Bonville was born on August 12 or 31, 1392, in Shute, Devon. His parents were John Bonville (who died in 1396) and Elizabeth Fitzroger (who died around 1414). William's grandfather was also named Sir William Bonville. He had been a Member of Parliament for Somerset and Devon many times. He was known as one of the most important people in the west country in the late 1300s. When his grandson William was born, Sir William "raised his hands to heaven and praised God." He and the Abbot of Newenham were William's godparents. Young William was set to inherit lands from both his father and grandfather. His grandfather had greatly increased the family's wealth.

William's father died when William was four years old. William likely grew up in his grandfather's home. His grandfather died in 1408, when William was still too young to legally own his lands. As was the custom, King Henry IV took control of William's lands and decided who he would marry. This was a valuable gift from the King. He first gave it to Sir John Tiptoft, and then to Edward, Duke of York. William had a younger brother, Thomas. By the time William became an adult, Thomas had already married a cousin of Robert, Baron Poynings. This connection helped William with his own marriage.

Marriages and Children

In 1414, William married Margaret Grey. She was the daughter of Reginald, Baron Grey of Ruthin. Lord Grey promised to pay Bonville 200 marks (a medieval money unit) on the wedding day. Bonville also promised to give lands worth 100 pounds to himself and his wife. Grey paid another 200 marks over the next four years. William and Margaret had four known children:

- William Bonville, who married Elizabeth Harington around 1443.

- Margaret Bonville, who married Sir William Courtenay.

- Philippa Bonville, who married Sir William Grenville.

- Elizabeth Bonville, who married Sir William Tailboys by November 1446.

These marriages helped Bonville make even more important connections with noble families and politicians.

Margaret died sometime between 1426 and 1427. After her death, William married Elizabeth Courtenay. She was the widow of John Harington and the daughter of Edward Courtenay, 3rd Earl of Devon. William and Elizabeth needed special permission from the Pope to marry. This was because Elizabeth was already a godmother to one of William's daughters. The church saw this as too close a family connection. Elizabeth was well-connected, being the sister-in-law of William Harington and aunt of Thomas Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon. This marriage greatly increased Bonville's ties to other noble families.

William and Elizabeth had no known children together. However, William had an illegitimate son with Isabel Kirkby:

- John Bonville (died 1491), who married Alice Dennis. His father gave him money in 1453 and left him a lot of property when he died.

Land and Wealth

Bonville's father and grandfather had both been very successful. So, when Bonville became an adult in 1414, he inherited lands that brought in about £900 a year. This was almost as much as the Earls of Devon earned. His lands included 18 manors (large estates). They were spread across England but mostly in Devon, especially around Shute, and in Somerset. These lands included what his grandfather had owned in Devon, Somerset, Dorset, and Wiltshire. His mother's family lands were mainly in Leicestershire, the East Midlands, Kent, and Sussex.

When Bonville's father and grandfather died, his mother and grandmother each held a third of his inheritance. This was a legal custom to protect widows. His mother remarried in 1397 to Richard Stucley. In 1410, she gave Stucley the right to use her inherited lands for his lifetime. When she died in 1414, Stucley gained lands in Devon and Wiltshire. Bonville sued his stepfather to get his mother's inheritance back. This legal fight lasted over six years, but he won in 1422. Bonville's grandmother lived until 1426. By then, Bonville had also inherited a lot of land from other relatives. This made him one of the wealthiest landowners in the West Country.

William Bonville's Public Service

Bonville served the King in France in 1415. He joined King Henry V's Agincourt campaign, traveling with the King's brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence. Bonville was knighted in Normandy before his 17th birthday. It is not known if he fought in the Battle of Agincourt itself.

In 1421, Bonville helped manage the Duke of Clarence's affairs after the Duke died in battle. Bonville must have been greatly trusted by Clarence, who was next in line to the English throne. Bonville returned to England before May 1421. King Henry V died in France in 1422. His six-month-old son, Henry VI, became King. His uncles, John, Duke of Bedford, and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, ruled for the baby King. The war in France continued. Bonville returned to France in 1423 with Gloucester's army. He fought in the campaign to retake Le Crotoy, bringing 10 men-at-arms and 30 archers.

When he returned to England, Bonville spent much of his time managing his large estates. Sometimes, there were violent disagreements with his neighbors. In 1427, he had a big fight with Sir Thomas Brooke. Bonville accused Brooke of illegally fencing off parkland and blocking roads his tenants needed. The matter went to Bonville's godfather, the Abbot of Newenham, who ruled against Brooke. Brooke had to pay Bonville's legal costs and remove his fences. By now, Bonville was also a royal official. He was appointed Sheriff of Devon in 1423. From 1431, he was a justice of the peace for Devon, Somerset, and Cornwall. He also investigated things like piracy, theft, and smuggling.

In 1437, King Henry VI began to rule on his own. Bonville was appointed to the King's Council. He was called a "King's knight." He was very active in stopping piracy off the coast of Cornwall. In 1454, the Duke of Burgundy even complained to the English government about how Bonville treated Burgundian ships. In 1440, Bonville and his friend Sir Philip Courtenay commanded a small fleet of ships to patrol the English Channel. They saw little action. Sometimes, they even lost ships to Portuguese merchants.

Feud with the Earl of Devon

The Start of the Conflict (1437–1440)

In 1437, Bonville was given the job of Steward of Cornwall for life. He received 40 marks a year for this. This immediately made him an enemy of the young Earl of Devon, Thomas Courtenay. Courtenay's wealth was already reduced, and giving Bonville this job hurt his income even more. The job was also a big source of power and influence. During the Earl's childhood, the Courtenay family's power in Devon weakened. Bonville and other local nobles became more important. This made it hard for the Earl to get back the power his family used to have. This tension between Bonville and Courtenay soon turned violent.

The King's decision to give Bonville the stewardship was the main reason for the Courtenay–Bonville feud. This feud was one of many fights between noble families in England during King Henry VI's reign. It got even worse in 1440. The King's council made a mistake by giving Courtenay a similar job: Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall. This job was almost the same as Bonville's. It upset the already delicate balance of power in the region. Violence broke out soon after, and "many men were hurt." In November 1442, both men were called before the King's Council. Bonville attended and promised to keep the peace. Courtenay, however, refused to come.

Bonville angered Courtenay by hiring men who had traditionally worked for the Earl. An agreement was forced upon them, but it did not work well. Bonville was fifty years old and had not been abroad for almost 20 years. But in 1443, the King's council appointed him seneschal (governor) of Gascony in France. They probably hoped that another trip to France would "distract his ample energies from the West Country." Bonville sailed in March 1444. He was supposed to bring 20 men-at-arms and 600 archers. King Henry gave him £100 for his campaign. However, their fleet likely did not leave Plymouth for many months. The army was small because most of the King's men were sent to Normandy, which was considered more important. Bonville's campaign achieved little, and he was seriously injured in a fight.

Escalation of the Feud (1440–1453)

Bonville was away from England for over two years and returned in April 1445. While he was gone, Courtenay had become more powerful in Devon. The King was weak and could not keep the peace in the southwest. King Henry was influenced by his favorite, William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk. Suffolk's government could not afford to upset the Earl of Devon. Bonville, however, found Suffolk to be a useful ally against the Earl. In 1444, Bonville joined Suffolk's group in France. Bonville played a key role in the engagement ceremony between King Henry and his future wife, Margaret of Anjou. In 1445, Bonville was made a baron. This was because of his successes in France and Suffolk's respect for him. He was known as Baron Bonville of Chewton. In 1446, Bonville stopped a revolt in Somerset where Wells Cathedral was attacked.

Bonville's connection with Suffolk did not last. In 1450, Suffolk was accused of crimes and sent away. He was later murdered on his way to Europe. One of Suffolk's biggest critics was Richard, Duke of York. The Earl of Devon soon allied himself with York to gain power in the West Country. Courtenay felt strong enough to restart his feud with Bonville. Bonville was hiring men in Taunton for sixpence a day. Courtenay launched attacks on Bonville's properties. This ended with Courtenay attacking Bonville's Taunton Castle with over 5,000 men. A writer at the time called it "the greatest disturbance." Edward Brooke, Lord Cobham, who was the son of an old enemy of Bonville's, fought alongside Courtenay. Courtenay's alliance with York was not as strong as he thought. When York came to Devon to restore order, he put both Bonville and Courtenay in prison for a month. Bonville had to give Taunton Castle to York. This part of the feud ended with a "loveday" (a day for making peace) between Bonville and Courtenay in 1451. This was an important event, attended by the King's representatives.

The Earl of Devon's alliance with York caused more problems in 1452. York felt left out of the government because the King had a new favorite, Edmund, Duke of Somerset. In February, York rebelled and marched on London. He faced the King's army at Blackheath. Courtenay stood with York. They surrendered without a fight. Bonville had raised men to join the King's army. He benefited from Courtenay's fall from favor with the King. Bonville was given a "free hand" in the region. He became the most important person in local politics. He was ordered to arrest and prosecute the Earl of Devon's men after Blackheath. The next year, King Henry showed his respect for Bonville by staying at Bonville's home in Shute during his visit to the southwest. Bonville received more jobs and responsibilities. He was confirmed as Steward of Cornwall and also made lieutenant of Aquitaine in France. He also received control of Exeter Castle and other lands. This made him very powerful in the west country. Bonville never took up his job in Gascony because England lost its lands in France at the Battle of Castillon in July 1453. King Henry appointed Bonville to a large group to investigate support for York's rebellion. The King also gave him £50.

King Henry's Illness and Yorkist Rule

In August 1453, King Henry became very ill and could not perform his royal duties. The government, already weak, was paralyzed. The political situation became very tense. Bonville attended a council meeting in Westminster in early 1454. It was rumored that Bonville was planning to join other lords and march on London. Everyone, including Bonville, was preparing for a national war.

The House of Lords eventually appointed the Duke of York as protector of the kingdom while the King was ill. York appointed Salisbury as chancellor. Although Courtenay was York's ally, he did not gain much from this. Bonville's position did not weaken during York's rule. In fact, he committed clear acts of piracy against foreign ships off the southwest coast, and he was not punished.

Battles and Bonville's Rise

In early 1455, King Henry suddenly recovered. York and Salisbury were removed from their government jobs and went back to their estates. National politics were very tense. The King called a great council in Leicester in May. Some writers of the time suggested that Somerset was turning the King against York. York and the Nevilles may have feared being arrested. They quickly reacted. They attacked the King's small army at the First Battle of St Albans on May 22. Courtenay fought for the King and was wounded. Bonville may have also supported the King, as one of his messengers was used by the King's advisors. However, he did not join the royal army. Some historians suggest that both Bonville and Courtenay were more interested in their own feud than the national one. King Henry was captured by the Yorkists after the battle. They now controlled the government again. Bonville did not turn against his King at this point. He attended the Yorkist parliament in September 1455. There, he voted for the Duke of York to be appointed protector. Bonville was appointed to a committee to improve naval defense. He also used his local influence to ensure that the vacant Bishopric of Exeter went to the Earl of Salisbury's youngest son, George Neville. In November, Bonville received a general pardon.

In the southwest, Bonville and his ally, James Butler, Earl of Wiltshire, were hiring many men. They announced that anyone strong enough to join them would get sixpence a day. Bonville's power in the southwest forced the Earl of Devon to act strongly. In April 1454, Devon brought an armed force of hundreds of men into Exeter in a planned attack. The plan failed, but Bonville was stopped from collecting a royal loan. In June, both Bonville and Courtenay were ordered by the King to keep the peace. They each had to promise £4,000 to do so. But they seemed to continue their fight. The situation in Devon was so chaotic that the court sessions in Exeter had to be canceled. Courtenay then terrorized the county with his army and robbed Bonville's houses. This ended on October 23, 1455, with a terrible crime. Courtenay's son, also named Thomas, and a small group of men attacked and murdered Nicholas Radford, one of Bonville's close advisors. A historian noted, "Nothing was done."

Bonville's Challenge and Courtenay's Power

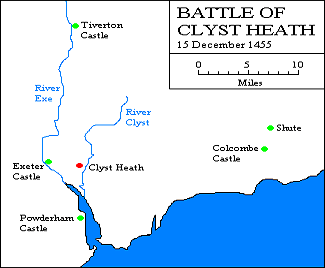

Radford's murder started a short, even more violent campaign between the two sides. A historian said it turned the region "periodically into a private jousting-field." The Bishop of Exeter complained that his tenants "dared not occupy the land." Bonville fought back against Courtenay by looting the Earl's Colcombe manor. Houses were robbed, cattle were stolen, and much loot was taken on both sides. Bonville wanted to fight Courtenay "on as equal terms as possible." He believed he had the "backing of God, the law, and the commonweal." On November 22, 1455, Bonville challenged Courtenay to a duel. Both men would be accompanied by their followers. He may have also been trying to draw the Earl out of Exeter, which Courtenay had been occupying for over two weeks. Or he wanted to distract him from his attack on Powderham Castle, which Bonville had already tried twice to stop. Courtenay had no choice but to accept Bonville's challenge. On December 15, the two sides met in battle near Clyst St Mary, east of Exeter. "Many people were killed." The battle seemed to have no clear winner, but if anyone lost, it was Bonville. He escaped alive but was dishonored as he had been the challenger. Two days later, Courtenay attacked Bonville's home in Shute, robbing it completely. Courtenay continued his campaign against Bonville for two months.

Neither side was strong enough to completely defeat the other. The fights were bad, but they did not spread much. Outside the region, the national political situation became very tense. The Bonville–Courtenay feud soon became just one part of the larger civil war. The Earl was later imprisoned for a short time. He died in 1458, with neither the feud resolved nor Bonville beaten. Bonville was made a Knight of the Garter in the same year.

Wars of the Roses

Courtenay, by his actions at St Albans, had gained the support of King Henry's powerful Queen, Margaret. She was strongly against the Yorkist party. Courtenay's son Thomas, who inherited the earldom, married the Queen's cousin. In 1458, Bonville's grandson married Katherine Neville, daughter of the powerful northern lord Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury. Historians suggest that Bonville managed to hide any support for the Duke of York during this time. He remained "outwardly loyal to Henry VI." One historian described Bonville as "a veteran servant of the House of Lancaster." He had been made a baron by King Henry VI and "clung to the court he had always served." He swore to support the rights of young Edward, Prince of Wales, against the Yorkists in 1459. In early 1460, he was ordered to raise an army in the southwest.

Within a few months, Bonville "revealed his true colors." He fought for the Yorkists at the Battle of Northampton in June 1460. Here, the victorious Yorkists captured King Henry again. Bonville was put in charge of keeping the King safe. Bonville attended the parliament in November that year. This parliament passed a law that would give York the throne after Henry's death. This meant the Prince of Wales would not inherit the throne. Queen Margaret and her nobles went north. They gathered an army and began to rob the Yorkist lords' estates there. York and the Earl of Salisbury, with their smaller army, marched north the next month. Bonville stayed in London. Bonville's son William marched with York. He died with York at the Battle of Wakefield, where the Lancastrian army crushed the Yorkist army on December 30, 1460.

Second Battle of St Albans

The Lancastrians then marched south. Salisbury's son, Richard, Earl of Warwick, had been left in charge of the King in London. Bonville, who had been in the southwest raising an army, returned to London. Warwick, Bonville, and other lords left London on February 12, 1461. They had an army to stop the Queen's force before it reached the city. They met at the Second Battle of St Albans on February 17, 1461. Bonville, along with Sir Thomas Kyriell, was put in charge of the King. The Yorkists had brought the King with them as the "nominal" head of their army. They were responsible for Henry's protection during the battle. This might mean that Bonville was still mainly motivated by a wish to protect the King he had served since he was young. Warwick's force was quickly surrounded by the fast-moving Lancastrian army. Warwick fled, leaving the battlefield and the King to the victorious Lancastrians. Bonville and Kyriell were also captured. The next day, they were called before the Queen and Prince Edward. It is possible that the King had promised them a pardon. However, with the Earl of Devon present, and likely at his urging, the two were tried for treason. The outcome was certain. Prince Edward "judged himself" and sentenced them to death. Both men were executed the same day. Bonville's death ended the main male line of the Bonville family. It also finally ended the Bonville-Courtenay "blood feud."

What Happened Next

Bonville's household was closed down almost immediately. However, some of his staff stayed with his widow. He did not leave a will when he died. His lands and wealth were divided into three parts: for his widow, his brother, and his illegitimate son. Since both of Bonville's legitimate sons had died before him, his lands and titles went to his one-year-old great-granddaughter, Cecily. She later married Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset. Some of the family lands had been set aside for the male line by Bonville's grandfather. These lands went to his younger brother, Thomas, and then to Thomas's son. Many of Bonville's followers went to work for Humphrey Stafford and Bonville's old ally Sir Philip Courtenay. The deaths of Bonville and Courtenay created a power vacuum in Devon. There was no clear dominant authority in the area after that.

Even though Bonville was executed for treason, he was not officially punished by law. This was because Edward of York, Richard of York's son, won the Battle of Towton a few weeks later on March 29, 1461. The Lancastrian army was destroyed. Queen Margaret escaped to Scotland, Henry went into hiding, and Edward claimed the throne as King Edward IV. After the battle, the Earl of Devon was captured and executed. Edward IV's cousin and chancellor, Archbishop George Neville, later called Bonville a "strenuous cavalier." The 1461 law against ex-King Henry mentioned Bonville's "prowess of knighthood." To recognize what Bonville and his family had done for the House of York, Edward gave Bonville's widow Elizabeth a large amount of land. She died on October 18, 1471, and never remarried.

Images for kids

-

TNA, document SC 8/269-13408: The petition of a Breton merchant, addressed to the King, seeking restoration of the merchant's ship and the goods it contained, captured at sea by Bonville and being held by him in Fowey. It was escapades such as this that led to the Duke of Burgundy's intervention on behalf of his own merchants.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |