Alexander Gordon (physician) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Gordon

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 20 May 1752 Milton of Drum, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 19 October 1799 (aged 47) Logie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

|

| Education | Marischal College, Aberdeen |

| Occupation | Physician and obstetrician |

| Known for | Demonstrating infectious nature of puerperal fever |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | Aberdeen Dispensary |

| Notable works | Treatise on the Epidemic Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen |

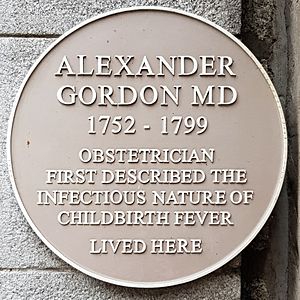

Alexander Gordon (born May 20, 1752 – died October 19, 1799) was a Scottish doctor. He was an obstetrician, a doctor who helps women during childbirth. Gordon is famous for showing that a serious illness called puerperal fever (also known as childbirth fever) could spread from person to person.

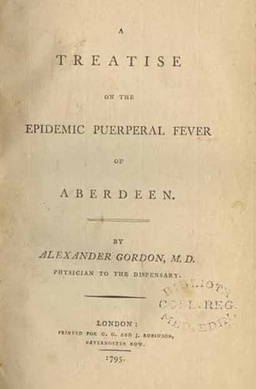

He carefully wrote down details of his visits to women who had this illness. He figured out that the sickness was carried by the midwives or doctors themselves. In 1795, he published his findings in a paper called "Treatise on the Epidemic Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen."

Based on his ideas, he suggested ways to stop the illness from spreading. He advised cleaning clothes with smoke and burning bed sheets used by sick women. He also said that doctors and midwives needed to be very clean. Gordon also saw a link between puerperal fever and erysipelas, a skin infection. We now know both are caused by the same type of bacteria. His work on how infections spread was done long before other famous doctors like Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes made similar discoveries.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Alexander Gordon was born in 1752 in a place called Milton of Drum, in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. His father, also named Alexander Gordon, was a farmer. Alexander had a twin brother, James, who became known for helping to develop the swede vegetable.

From 1771 to 1775, Alexander Gordon studied at the University of Aberdeen's Marischal College. He earned a degree called Master of Arts. He wanted to be a doctor, so he learned by watching doctors at Aberdeen Infirmary.

At that time, Aberdeen did not offer medical degrees. So, he went to Leyden, Holland, which had a top medical school. Many Scottish students went there to study medicine. In 1779–80, he also attended lectures in Edinburgh. He didn't get a medical degree from these places. However, he learned enough to pass an exam at the Company of Surgeons in England. This allowed him to work as a surgeon.

Medical Career

In 1780, Gordon joined the Royal Navy as a surgeon's helper. He became a full surgeon in 1781. In 1785, he left the navy but still received half pay. He then moved to London to learn more about childbirth.

He attended lectures and gained hands-on experience at hospitals like the Store Street Lying-in Hospital. He also learned about surgery at the Westminster Hospital.

Gordon knew there wasn't a doctor specializing in childbirth in Aberdeen. So, he returned there in 1785. In 1786, he became a doctor at the Aberdeen Dispensary. This job meant he saw patients both at the clinic and in their homes. The University of Aberdeen gave him a medical degree (MD) in 1788.

Understanding Childbirth Fever

Between 1789 and 1792, Aberdeen had two outbreaks of illness. One was erysipelas, a skin infection, and the other was puerperal fever. Gordon knew about puerperal fever from his time in London. He was very good at keeping detailed notes, which was common during the Scottish Enlightenment.

He wrote down the names of midwives and doctors who had visited sick women. By looking at the dates, he realized that the medical helpers were spreading the disease. He even admitted that he himself had carried the illness to many women. He said it was "a disagreeable declaration" to admit this.

Gordon used common treatments for illnesses back then, like bleeding and purging. But he also strongly believed in cleanliness for doctors and nurses. This idea was not widely accepted at the time.

He thought puerperal fever was caused by a "specific contagion or infection." This was different from the popular idea that bad air (miasma theory) caused diseases. He believed that "putrid particles" were passed on. He thought that after birth, these particles could easily enter the mother's body. Later, Semmelweis's work helped prove this idea.

Gordon also saw a connection between the spread of puerperal fever and erysipelas. He concluded that the same infectious matter caused both.

His ideas on preventing illness were also new. He wrote that a patient's clothes and bedding should be burned or cleaned very well. He also said that nurses and doctors should wash themselves and clean their clothes with smoke. These ideas were influenced by naval and military surgeons who improved health by making things cleaner.

Gordon had named patients and midwives in his book. This made him unpopular with both groups. The midwives "raised an odium against my practice," he wrote. He knew the risks of sharing names, saying, "I saw the danger of disclosing the fatal secret." As people in Aberdeen turned against him, he felt hurt. He described the "ungenerous treatment" he received from the very women he tried to help. By the end of his time in Aberdeen, many people were openly against him.

Gordon's clear proof that childbirth fever was contagious was published many years before others. Oliver Wendell Holmes published his work 48 years later and gave Gordon credit. Ignaz Semmelweis published his important work 66 years after Gordon's book, but he did not mention Gordon.

The Practice of Physik

Gordon wrote a medical textbook between 1786 and 1795. This book stayed with his family until 1913. It was then given to the Library of Aberdeen University. In it, Gordon described how doctors practiced medicine at the time. He showed that medical decisions were starting to be based on observations.

He admired doctors who used logic and evidence. Yet, he still used older methods like bleeding patients. He also believed doctors should be kind and caring to their patients. This idea was influenced by John Gregory, a professor who taught about medical ethics.

Family and Later Life

On February 5, 1784, Gordon married Elizabeth Harvie. They had two daughters. One, Elizabeth, died young. The other, Mary, married one of Gordon's students. Gordon's grandson, Alexander Harvey, later became a professor at the University of Aberdeen.

Gordon left Aberdeen in 1795. He was called back to the Royal Navy. He served as a surgeon on two ships, HMS Adamant and HMS Overyssel.

He became sick with tuberculosis, a lung disease. He returned to his brother James's farm in Logie, Aberdeenshire. Alexander Gordon died there in 1799.

Selected Books

- Observations of the Efficacy of Cold-Bathing in the Prevention and Cure of Diseases. (1786)

- Treatise on the Epidemic Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen (1795)

- The practice of Physick (2011) (This was a later transcription of his original notes.)

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |