Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

|

|

|---|---|

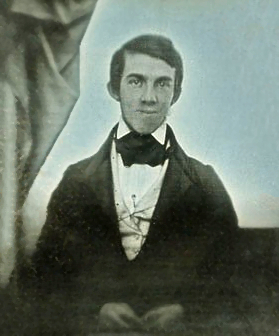

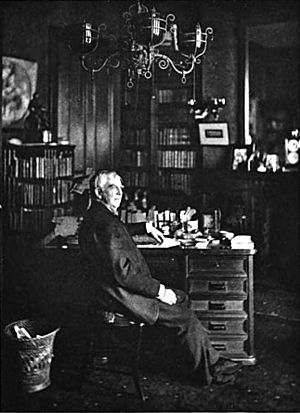

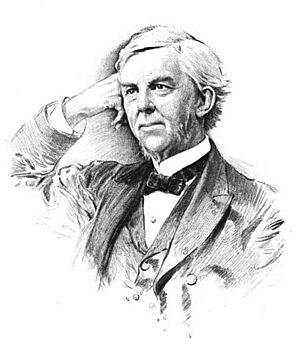

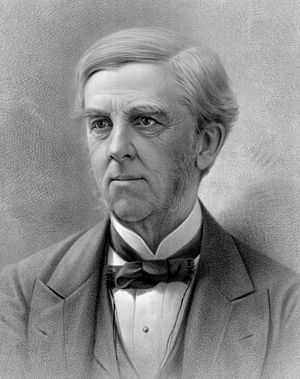

Holmes, around 1879

|

|

| Born | Oliver Wendell Holmes August 29, 1809 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 7, 1894 (aged 85) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Harvard University (AB, MD) |

| Spouse |

Amelia Lee Jackson

(m. 1840; died 1888) |

| Children | 3, including Oliver Jr. |

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (born August 29, 1809 – died October 7, 1894) was a famous American doctor, poet, and writer from Boston. He was known for being good at many different things. People at the time thought he was one of the best writers.

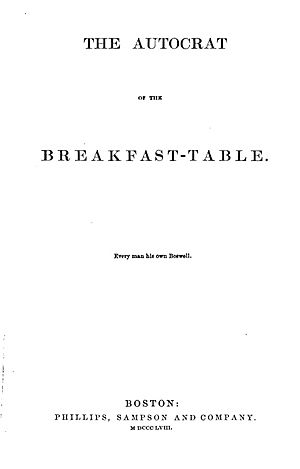

He was part of a group called the fireside poets. These poets were popular because their writing was easy to understand and often told stories. Holmes's most famous books were the "Breakfast-Table" series, which started with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He also helped make important changes in medicine. Besides writing, Holmes was a doctor, a professor, and an inventor. He even studied law, but he never worked as a lawyer.

Holmes was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He went to Phillips Academy and Harvard College. After college, he first studied law, but then decided to become a doctor. He started writing poems when he was young. One of his most famous poems, "Old Ironsides", was published in 1830. This poem helped save the historic ship USS Constitution from being taken apart.

After studying medicine in Paris, Holmes earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1836. He taught at Dartmouth Medical School and then at Harvard. He even served as the dean there for a while. During his time as a professor, he pushed for new ideas in medicine. He famously suggested that doctors could spread puerperal fever (a dangerous infection) from one patient to another. This idea was very new and surprising at the time. Holmes stopped teaching at Harvard in 1882. He kept writing poems, novels, and essays until he passed away in 1894.

Holmes was friends with many famous writers in Boston, like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He had a big impact on writing in the 1800s. Many of his works were published in The Atlantic Monthly magazine, which he actually named. He received many awards from universities for his writing and other achievements. Holmes often wrote about his home area of Boston. His writing was usually funny or felt like a conversation. Some of his medical writings, especially his 1843 essay about how childbed fever could spread, were very advanced for his time. He also helped make terms like Boston Brahmin and anesthesia popular. He was the father of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who became a judge on the highest court in the United States.

Contents

Early Life and School Days

Growing Up in Cambridge

Oliver Wendell Holmes was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on August 29, 1809. His childhood home was near Harvard Yard. People said that the famous Battle of Bunker Hill was planned in that very house. His father, Abiel Holmes, was a church minister and a history lover. His mother, Sarah Wendell, came from a rich family. Holmes was named after his grandfather, who was a judge. His family also included famous people like Anne Bradstreet, who was the first published American poet.

From a young age, Holmes was small and had asthma. But he was very smart and learned things quickly. When he was eight, he and his younger brother, John, secretly watched the last public hanging in Cambridge. Their parents were not happy about this. Holmes loved to explore his father's large library. He later wrote that it was full of "solemn folios" (big, serious books) about religion. After reading poets like John Dryden and Alexander Pope, young Holmes started writing his own poems. His first poem was written when he was 13. His father wrote it down for him.

Holmes was a talented student, but his teachers often told him off. He talked a lot and liked to read stories during school. He went to different schools, including a private academy called the "Port School." One of his classmates there was Margaret Fuller, who later became a famous writer and critic. Holmes admired her intelligence.

College Life and Early Writing

When Holmes was 15, his father sent him to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. His father hoped he would become a minister, as the school taught strict religious ideas. But Holmes was not interested in being a theologian. He did not enjoy his year there. Even though he joined a literary club, he disliked most of the teachers' "narrow-minded" attitudes. However, one teacher noticed his talent for poetry and told him to keep writing. Soon after his sixteenth birthday, Holmes was accepted into Harvard College.

At Harvard, Holmes lived at home for his first few years. He was only "five feet three inches" tall, so he didn't join sports teams. Instead, he hung out with a group of students who liked to smoke and talk. Because he lived in town and was a minister's son, he could mix with different groups of students. He also became friends with Charles Chauncy Emerson, who was Ralph Waldo Emerson's brother. In his second year, Holmes was one of 20 students who won a special award for their studies. Even with his good grades, he admitted he didn't "study as hard as I ought to." But he was very good at languages like French, Italian, and Spanish.

Holmes was interested in law, medicine, and writing. He joined the Hasty Pudding club, where he was the Poet and Secretary. He also joined the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. With two friends, he wrote a small book of funny poems about a new art gallery in Boston. He wrote a "light and sarcastic" poem for his graduation, which everyone loved. After graduating, Holmes planned to become a lawyer. He studied at Harvard Law School. But by January 1830, he didn't like law studies. He wrote, "I am sick at heart of this place."

Becoming a Poet

The year 1830 was very important for Holmes as a poet. Even though he didn't like law, he started writing poems for fun. By the end of the year, he had written over fifty poems. He gave twenty-five of them to The Collegian, a magazine started by his Harvard friends. Four of these poems became very well known later on. Nine more of his poems were published without his name in a pamphlet in 1830.

In September 1830, Holmes read in a newspaper that the famous ship USS Constitution was going to be taken apart. This made Holmes write "Old Ironsides" to stop it. The patriotic poem was printed the very next day. It was quickly printed in newspapers across the country. The poem made people feel so strongly that the historic ship was saved.

Holmes published only five more poems that year. His last big poem of the year was "The Last Leaf." It was inspired by a local man named Thomas Melvill, who was one of the "Indians" from the 1774 Boston Tea Party. Holmes later wrote that Melvill reminded him of "a withered leaf" still hanging on a branch in winter. The writer Edgar Allan Poe called this poem one of the best in the English language. Years later, Abraham Lincoln also loved the poem.

Even though he had early success as a writer, Holmes didn't think about becoming a full-time author. He later wrote that writing was like a "sickness" that quickly took over.

Medical Career and Reforms

Medical Training

After giving up on law, Holmes decided to study medicine. In 1830, he moved to Boston to attend medical college. Back then, students studied only five main subjects: medicine, anatomy, surgery, obstetrics (childbirth), chemistry, and materia medica (medicines). Holmes became a student of James Jackson, a doctor and father of a friend. He also worked part-time in the hospital's chemistry lab.

Holmes was upset by the harsh medical treatments of the time, like bloodletting (taking blood out of a patient). He liked his mentor's ideas, which focused on carefully watching the patient and being kind. Even with little free time, he kept writing. He wrote two essays about life from his boardinghouse's breakfast table. These essays later became part of his famous "Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table" series.

In 1833, Holmes went to Paris to continue his medical studies. Paris had very advanced medical training at the time. At 23, Holmes was one of the first Americans to learn the new "clinical" method at the famous École de Médecine. He hired a French tutor because all the lessons were in French. He quickly got used to his new surroundings. He wrote to his father, "I love to talk French, to eat French, to drink French."

At a hospital in Paris, he studied under Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis. Louis showed that bloodletting, a common practice for centuries, didn't work. Louis believed doctors should help nature heal the body, not get in its way. When Holmes returned to Boston, he became a strong supporter of this idea. Holmes earned his medical degree from Harvard in 1836. His first collection of poems was published that same year. But Holmes was ready to start his medical career and thought writing was just a hobby.

Pushing for Medical Changes

After graduating, Holmes quickly became well-known in the medical community. He joined several medical societies in Boston. He also won a big award from Harvard Medical School for his paper on using the stethoscope. Many American doctors at the time didn't know about this device.

In 1837, Holmes worked at the Boston Dispensary. He was shocked by the dirty conditions there. That year, he won two more essay prizes. Wanting to focus on research and teaching, he and three friends started the Tremont Medical School. It later joined with Harvard Medical School. There, he taught about diseases and how to use microscopes. He often criticized old medical practices. He once joked that if all current medicine was thrown into the sea, "it would be all the better for mankind." For the next ten years, he had a small medical practice but spent most of his time teaching. He taught at Dartmouth Medical School from 1838 to 1840. He was also chosen as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1838.

After leaving Dartmouth, Holmes gave a series of three lectures to expose false medical ideas, or "quackeries." He spoke seriously about how people used bad reasoning and false information in things like "Astrology and Alchemy." He called homeopathy, a medical system, a "pretended science." In 1842, he published an essay where he again spoke out against it.

In 1846, Holmes created the word anaesthesia. He predicted his new word "will be repeated by the tongues of every civilized race of mankind."

Understanding Childbed Fever

In 1842, Holmes heard a lecture about puerperal fever, also called "childbed fever." This disease caused many women to die after giving birth. Holmes became very interested in it. He spent a year looking through medical reports and writings to find out what caused it and how to stop it. In 1843, he shared his research. He published a paper called "The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever."

His essay argued that childbed fever was spread from patient to patient by doctors. This was a very new idea at the time, before people fully understood germ theory of disease. Holmes believed that bed sheets, washcloths, and clothes could carry the infection. He collected many examples to support his idea. He told stories of doctors who got sick and died after doing autopsies on infected patients. He said that if even one case of childbed fever happened in a doctor's practice, that doctor should clean their tools, burn their clothes, and stop helping with births for at least six months.

When it was first published, many people didn't notice his paper. But later, two well-known professors of obstetrics, Hugh L. Hodge and Charles Delucena Meigs, strongly disagreed with Holmes. In 1855, Holmes published a new version of his essay. He added more cases and directly spoke to his opponents. He wrote, "I had rather rescue one mother from being poisoned by her attendant, than claim to have saved forty out of fifty patients to whom I had carried the disease." He added, "I beg to be heard in behalf of the women whose lives are at stake."

A few years later, Ignaz Semmelweis in Vienna came to similar conclusions. He started making doctors wash their hands with a chlorine solution before helping with births. This greatly lowered the death rate from childbed fever. Holmes's work, though controversial then, is now seen as a very important step in understanding how germs cause disease.

Teaching at Harvard

In 1847, Holmes became a professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard Medical School. He was the dean until 1853 and taught until 1882. Soon after he started, male students complained when he thought about letting a woman named Harriot Kezia Hunt join the school. Because of opposition from students, university leaders, and other teachers, she was asked to leave. Harvard Medical School didn't admit a woman until 1945.

Holmes's training in Paris taught him to show his students how diseases affected the body. He taught that doctors should look at the real causes of illness. Students liked Holmes and called him "Uncle Oliver."

Family Life and Later Years

Marriage and Home Life

On June 15, 1840, Holmes married Amelia Lee Jackson in Boston. She was the daughter of a judge and the niece of James Jackson, the doctor Holmes had studied with. The judge gave the couple a house, where they lived for eighteen years. They had three children: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (who became a famous judge), Amelia Jackson Holmes, and Edward Jackson Holmes.

In 1848, Amelia Holmes inherited some money. She and her husband used it to build a summer house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Starting in July 1849, the family spent "seven blessed summers" there. Holmes had recently stopped his private medical practice, so he could spend time with other writers in the area. He enjoyed measuring the size of trees on his property. He wrote that he had "a most intense, passionate fondness for trees." But it cost a lot to keep up the Pittsfield home, so the Holmes family sold it in May 1856.

While he was dean in 1850, Holmes was a witness in a famous murder case. Both the victim and the killer were Harvard graduates. Holmes gave a lecture in memory of the victim.

That same year, Holmes admitted three African-American men to the Medical School. This was a very controversial decision. Many students signed a paper saying they didn't want black students in their classes. Holmes told the black students they couldn't continue after that semester. Even though he supported education for black people, he was not an abolitionist (someone who wanted to end slavery immediately). He felt that the movement was going too far. This disappointed his friends, but Holmes wanted to help people in his own way. He believed slavery could end peacefully and legally.

From 1851 to 1856, Holmes gave many lectures. He talked about "Medical Science," "Lectures and Lecturing," and "English Poets." He traveled around New England and earned money for his talks. He also published a lot during this time. But as society changed, Holmes often found himself disagreeing with people. He was criticized for not being against slavery and for not supporting the temperance movement (which wanted to ban alcohol). Because of this, he stopped lecturing and returned home.

Later Success and the Civil War

In 1856, a group of writers created The Atlantic Monthly magazine. Holmes's friend James Russell Lowell edited it. Famous writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote for it. Holmes not only named the magazine but also wrote many pieces for it over the years. For the first issue, Holmes wrote a new version of his earlier essays, "The Autocrat at the Breakfast-Table." This work was very popular. It helped The Atlantic Monthly become a success. The essays were published as a book in 1858 and sold ten thousand copies in three days. This became his most famous work. Its follow-up, The Professor at the Breakfast-Table, started appearing in the magazine in 1859.

Holmes's first novel, Elsie Venner, started appearing in the Atlantic in December 1859. It was about a young woman whose mother was bitten by a rattlesnake while pregnant. This made the daughter's personality half-woman, half-snake. The novel received mixed reviews.

Around 1860, Holmes invented the "American stereoscope." This was a device that let people look at pictures in 3-D. He later wrote that it was very convenient and became very popular in Boston. Holmes did not patent his invention, so he didn't make money from it.

Soon after the Civil War began in 1861, Holmes started writing to support the Union. He had criticized those who wanted to end slavery before, but now his main concern was keeping the country together. In September, he wrote an article where he proudly said he supported the Union. He wrote that "War has taught us... what we can be." However, in 1863, Holmes wrote that slavery was the main reason for the country being divided.

Holmes also had a personal reason to care about the war. His oldest son, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., joined the Army in April 1861, even though his father didn't want him to. His son was hurt three times in battle. Holmes wrote an article about searching for his son after he was injured.

During the Civil War, Holmes's friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow began translating a famous Italian poem. Starting in 1864, Longfellow invited friends, including Holmes, to help him every week. This group was called the "Dante Club." The translation was published in 1867. That same year, Holmes's second novel, The Guardian Angel, was published.

Later Life and Passing

Holmes remained famous in his later years. The Poet at the Breakfast-Table was published in 1872. This book was calmer and more thoughtful than his earlier works. Holmes wrote, "As people grow older... they often think with a kind of pleasure of losing their dearest possessions." In 1876, at age seventy, Holmes published a biography of his friend John Lothrop Motley. The next year, he published a collection of his medical essays. He was chosen as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1880. He retired from Harvard Medical School in 1882 after 35 years as a professor. The university made him a professor emeritus after his last lecture.

In 1884, Holmes published a book about his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson. This book was very helpful for later writers studying Emerson. In 1885, Holmes's last novel, A Mortal Antipathy, was published. Later that year, Holmes gave money to Walt Whitman, another writer, even though he didn't like Whitman's poetry. He also convinced his friend John Greenleaf Whittier to do the same.

Holmes started to slow down his writing and social events after his youngest son died suddenly. In late 1884, he traveled to Europe with his daughter Amelia. In Great Britain, he met writers like Henry James and Alfred Tennyson. He received several honorary degrees from universities there. Holmes and Amelia then visited Paris, which had been very important to him in his younger years. He met the famous scientist Louis Pasteur, whose studies had helped reduce deaths from childbed fever. Holmes called Pasteur "one of the truest benefactors of his race." After returning to the United States, Holmes published a travel book called Our One Hundred Days in Europe.

In June 1886, Holmes received another honorary degree from Yale University. His wife, who had been sick for months, died on February 6, 1888. His daughter Amelia died the next year. Even though his eyesight was getting weaker and he worried about becoming old-fashioned, Holmes found comfort in writing. He published Over the Teacups, his last "table-talk" book, in 1891.

Towards the end of his life, Holmes noticed that most of his friends had passed away. He said, "I feel like my own survivor... We were on deck together as we began the voyage of life... Then the craft which held us began going to pieces." His last public appearance was in Boston in 1893, where he read a poem.

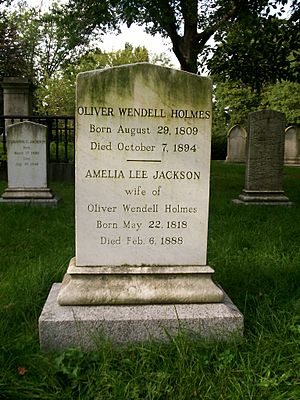

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. died peacefully in his sleep on Sunday, October 7, 1894. His son wrote, "His death was as peaceful as one could wish for those one loves. He simply ceased to breathe." Holmes was buried next to his wife in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

His Writing Style

Poetry

Holmes was one of the fireside poets, along with William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and John Greenleaf Whittier. These poets were popular in both America and Europe. Their writing was known for being family-friendly and traditional. Holmes believed poetry had "the power of transfiguring the experiences... into an aspect which comes from the imagination."

Because he was so popular, Holmes was often asked to write special poems for events. These were called commemorative poems. He wrote them for memorials, anniversaries, and birthdays. He was known for writing serious poems about loyalty and trust, and funny poems for celebrations.

Many of Holmes's poems were based on what he saw around him. This is true for "Old Ironsides" and "The Last Leaf," which he wrote when he was young. In poems like "The Chambered Nautilus" and "The Deacon's Masterpiece or The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay," Holmes focused on everyday objects he knew well. Some of his works also talked about his family history. For example, the poem "Dorothy Q" is about his great-grandmother. The poem uses short, rhyming lines:

O Damsel Dorothy! Dorothy Q.!

Strange is the gift that I owe to you;

Such a gift as never a king

Save to daughter or son might bring,—

All my tenure of heart and hand,

All my title to house and land;

Mother and sister and child and wife

And joy and sorrow and death and life!

Holmes often used humor to balance out strong emotions in his poems. His poetry often connected nature to human relationships and social lessons. Poems like "The Ploughman" were even quoted in the Old Farmer's Almanac. He also wrote several hymns.

Prose Works

Even though he was mainly known as a poet, Holmes wrote many medical papers, essays, novels, and memoirs. His prose (writing that isn't poetry) covered topics from medicine to religion, psychology, and society. One writer said Holmes created a new type of essay that mixed stories with important ideas. His works often combined different styles, including poetry, essays, and conversations.

Holmes became famous worldwide with his "Breakfast-Tables" series. These books were popular because they felt like conversations. Readers felt a close connection to the author. The conversational style made it easy to share thoughts and ideas.

The different characters in the books represent different parts of Holmes's life. For example, the speaker in the first book is a doctor who studied in Paris. The second book is told by a professor at a medical school. Even though the characters talk about many things, the conversations always lead back to Holmes's ideas about science, medicine, and how they relate to the mind. Autocrat especially talks about big ideas like who we are, language, life, and truth.

Holmes called his novels "medicated novels." Some people think these books were new and exciting because they explored ideas that later became part of psychology. For example, The Guardian Angel looks at mental health and forgotten memories. A Mortal Antipathy shows a character whose fears come from a past trauma. Holmes's novels were not very popular with critics when he was alive.

His Impact and Legacy

Holmes was highly respected by other writers and had many fans around the world. People often said he was very intelligent. One theologian called him "intellectually the most alive man I ever knew." Another critic praised Holmes, saying he was "a man of genius." However, some critics thought his writing was more like a hobby for a doctor.

Like Samuel Johnson in England, Holmes was known for his great conversation skills. Even though he was famous across the country, Holmes loved and promoted Boston culture. He often wrote from a Boston point of view. He believed Boston was "the thinking centre of the continent." He also created the term Boston Brahmin to describe the oldest and most intellectual families in Boston.

His essay on childbed fever is considered "the most important contribution made in America to the advancement of medicine" up to that time. But Holmes is most famous as a humorist and poet. One critic called him "one of the wittiest and most original of modern poets."

Poems by Holmes and the other fireside poets were often memorized by schoolchildren. Even though memorizing poems became less common by the 1890s, these poets were still seen as the ideal New England poets. Today, some scholars say that Holmes's work is less often included in American literature books.

The library at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, where Holmes went to school, is named the Oliver Wendell Holmes Library in his honor. It holds many of his personal papers, essays, and poems. In 1915, people in Boston placed a special memorial seat and sundial behind Holmes's last home. It was placed where he could see it from his library. King's Chapel in Boston, where Holmes went to church, has a memorial tablet for him. It lists his achievements: "Teacher of Anatomy, Essayist and Poet." It ends with a quote from a Latin poem: "He mingled the useful with the pleasant."

Selected Works

- Poetry

- Poems (1836)

- Songs in Many Keys (1862)

- Medical Studies

- Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence (1855)

- Table-talk books

- The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858)

- The Professor at the Breakfast-Table (1860)

- The Poet at the Breakfast-Table (1872)

- Over the Teacups (1891)

- Novels

- Elsie Venner (1861)

- The Guardian Angel (1867)

- A Mortal Antipathy (1885)

- Biographies and Travel

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1884)

- Our Hundred Days in Europe (1887)

Images for kids

-

USS Constitution sailing in 1997

-

Holmes's children in 1854: Edward Jackson Holmes, Amelia Jackson Holmes, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

-

A copy of a Holmes-type stereoscope

See also

In Spanish: Oliver Wendell Holmes (escritor) para niños

In Spanish: Oliver Wendell Holmes (escritor) para niños

- Epeolatry, a term coined by Holmes

- George Livermore, a childhood classmate

- Wendell, North Carolina, a town named after Holmes

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |