Anton Constandse facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

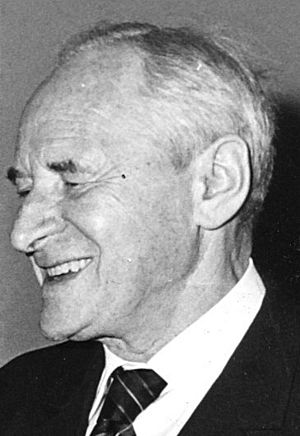

Anton L. Constandse

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 13, 1899 Brouwershaven

|

| Died | March 23, 1985 (aged 85) The Hague

|

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Other names | Dr. A. Elsée, G. Hamer, Pol de Beer, F.C.O., C.G.G., G.L. |

| Education | Ph.D. in Spanish literature (1951) |

| Alma mater | University of Amsterdam |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

Anton Levien Constandse (born September 13, 1899, died March 23, 1983) was a Dutch writer and journalist. He was known for his ideas about anarchism, which is a belief in societies without strict government rules. He spent his life sharing his thoughts through writing and speaking.

Contents

Anton Constandse: A Life of Ideas

Anton Constandse was a Dutch writer and journalist. He was born in 1899 and lived until 1983. He became famous for his strong beliefs and his work as a journalist.

Early Life and Anarchist Beliefs

Anton grew up as the son of a hotel owner. From 1914 to 1918, he went to a school to become a teacher.

When World War I happened, he started to believe that wars were wrong. He joined a group called the Social-Anarchist Youth Organisation in 1919. In this group, he supported the idea of individual freedom. He thought that people should be free from too many rules.

Instead of becoming a teacher, Anton decided to spread his anarchist ideas. He started two monthly magazines. These were called Alarm (from 1922 to 1926) and Opstand (meaning "Revolt," from 1926 to 1928). His writings helped to shape new ideas for anarchism in the Netherlands.

In 1927, Anton wrote an article that caused some trouble. He suggested that people should protest against a warship being sent to China. Because of this, he was found guilty of encouraging rebellion and spent two months in prison.

Fighting Against Fascism

In the 1930s, Anton focused on fighting against fascism. Fascism is a type of government where one leader has total power. When Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Anton changed his mind about being against all wars. He realized that some fights were necessary to stop bad things from happening.

He saw the Spanish Civil War as a chance for people to create a society without a strong government. But when the side he supported lost the war, he changed his views. He started to think about why some people might want a strong leader.

Anton also studied to become a French teacher. However, a law in 1933 stopped schools from hiring people who were part of leftist groups. This meant he could not work as a teacher.

World War II and After

On October 7, 1940, during World War II, German forces arrested Anton. He was sent to different concentration camps. He spent 13 months in Buchenwald camp. After that, he was moved to other camps, including Kamp Vught.

In September 1944, he was freed from the camp. He then lived through the difficult "hunger winter" of 1944 in The Hague.

After the war, Anton became a journalist for a newspaper called Algemeen Handelsblad. He had met the editor, D.J. von Balluseck, while they were both held captive. Anton became the head of the newspaper's foreign news section. He often wrote articles that went against the popular ideas of the Cold War. He criticized both the Soviet Union and the United States. He believed their actions were not good for world peace.

In 1956, he wrote an article about the Hungarian Uprising. He argued that Western countries should not get involved. He feared it could lead to a nuclear war. This article even caused a big argument in the newspaper office. Anton stayed on the newspaper's editorial board until he retired in 1964.

Later Years and Legacy

Even after retiring, Anton continued to write. He wrote for magazines like De Groene Amsterdammer and Vrij Nederland. He also made radio programs and gave lectures at the University of Amsterdam. He taught about the history of Spain and Latin America.

In the 1960s, many young people were looking for new ideas. Anton became an inspiration to them. He started to see his anarchist ideas as a way to change culture, not just politics. From 1973, he also edited an anarchist magazine called De AS.