Battle of Berea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Berea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

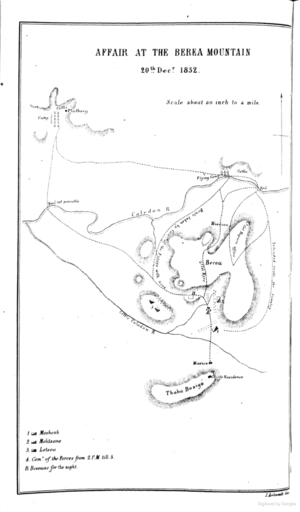

Map of the Battle of Berea sent by Sir George Cathcart to London |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Basuto Taung |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Cathcart | Moshoeshoe I | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 1,000 | c. 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 38 killed 14 wounded |

c. 50 killed and wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Berea was a fight between British soldiers and the Basuto and Taung people. It happened on December 20, 1852. The British forces were led by Sir George Cathcart. The Basuto and Taung forces were led by their King, Moshoeshoe I.

The battle started when British soldiers crossed the Caledon River in southern Africa. Their goal was to take Basuto cattle. This was meant as a punishment for past cattle raids by the Basuto. However, the Basuto fought back strongly. The British also had some planning problems. They ended up taking far fewer cattle than they wanted.

The British soldiers then pulled back to regroup. They had lost many men. But before more fighting could happen, a peace agreement was made. The Basuto agreed to return some cattle. They also promised to stop raiding British subjects.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Basuto Nation Forms

In the early 1800s, different tribes settled near the Caledon River in southern Africa. These included groups speaking Sotho, Nguni, and Tswana. The Sotho-speaking people were the largest group. They slowly absorbed the other tribes.

King Moshoeshoe I brought these Sotho-speaking groups together. This happened during a time of great change called the Lifaqane. By 1828, Moshoeshoe had created the Basuto nation. In African societies, taking cattle from rival tribes was important. It showed a chief's power and helped him gain followers. Chiefs would share the stolen cattle with their people. This system was called mafisa.

In the 1820s, the Basuto faced cattle raids from the Koranna. These were Khoekhoe people who had moved from the Cape. This was when the Basuto first saw horses and guns used in battle. After some early struggles, the Basuto got their own horses and guns. They also collected gunpowder. By 1843, Moshoeshoe had more horses and guns than any other chief in South Africa. However, most of their guns were older flintlock models. Newer percussion lock muskets were becoming common.

Basuto and British Relations

In 1843, Moshoeshoe signed a treaty with the British governor, Sir George Napier. This made the Basuto allies of the British. The Basuto were supposed to stop Boer groups from moving into the Cape. In return, they received money or ammunition each year.

In 1845, a new governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland, signed another treaty. This one aimed to solve land disputes between the Boers and African tribes. Moshoeshoe was not happy with this treaty. It took away some Basuto land and their yearly payment.

In 1848, the new Cape governor, Sir Harry Smith, made Moshoeshoe sign another agreement. Moshoeshoe agreed that the British had power over lands north of the Orange River. But he kept his traditional rights. This agreement also aimed to create an alliance between the British and Basuto. Other similar treaties created the Orange River Sovereignty.

In the north-east, the Basuto and their Taung allies often raided cattle from the Batlakoa and Koranna. The British leader in the Orange River Sovereignty, Major Henry Douglas Warden, thought the Basuto were mostly to blame. In 1849, Warden started drawing new borders for the tribes. He ignored Moshoeshoe's claims to some areas.

Moshoeshoe felt the British were not protecting him from the Batlakoa and Boers. Many of his people thought he was being weak. On June 25, 1851, Warden demanded that the Basuto return 6,000 cattle and 300 horses. These were supposedly stolen from past raids. Warden gathered about 2,500 British, Boer, and African soldiers. On June 28, Warden's force attacked the Taung to take stolen cattle. On June 30, Warden's army was defeated by a Basuto-Taung army at the Battle of Viervoet.

In October, Moshoeshoe wrote to Smith and Warden. He explained he had acted in self-defense. He wanted to stay friends with the British. In February 1852, a British official named William Hogge admitted the Cape government had made mistakes. Hogge agreed to redraw some borders and stop interfering in tribal conflicts. But he insisted the Basuto return cattle and horses stolen from the Rolong and Boer settlers.

Moshoeshoe returned 400 cattle and horses by March 20. But he stopped when he realized that getting Basuto lands back depended on returning all the cattle. The Basuto preferred to fight rather than give up their cattle. The new British commander, Major-General Sir George Cathcart, was waiting. He needed to finish fighting the Xhosa in the Eighth Xhosa War before dealing with the Basuto.

Getting Ready for Battle

After largely defeating the Xhosa, Cathcart led an army north in November 1852. His force had about 2,500 men. It included soldiers from different British regiments. There were also cavalry, like the Cape Mounted Rifles and the 12th Royal Lancers. They also had cannons and Congreve rockets.

On November 13, Cathcart met with Basuto leaders. He wanted to decide how many cattle the Basuto should return. They decided the Basuto had to give 10,000 cattle and 1,000 horses in three days. Cathcart warned that if they resisted, he would take three times that amount.

Two days later, Moshoeshoe visited Cathcart's camp. He asked for more time to gather the cattle. Cathcart refused and threatened to take the cattle by force. Moshoeshoe warned him, saying "a dog when beaten would show its teeth." Cathcart still believed the Basuto would not fight. He left more than half his army at the camp.

Moshoeshoe held a pitso (a formal meeting) at Thaba Bosiu. He urged his people to collect as many cattle as they could. By November 18, they had 3,500 cattle. Basuto messengers asked for more time. The British refused. When the Basuto did not deliver more cattle, Cathcart set up camp. It was near the Caledon River, about 12 miles north-west of Thaba Bosiu. Moshoeshoe's brother, Mopeli, visited Cathcart. He agreed to lead the British to Thaba Bosiu the next day for more talks.

After Mopeli left, Cathcart changed his mind. He ordered his troops to march on Thaba Bosiu at 4 a.m. on December 20. A small group of soldiers stayed to guard the camp. The rest of the army was split into three groups, called columns.

- The first column, led by Lieutenant-Colonel G. Napier, had 119 cavalry and 114 Lancers. They were to go around the Berea plateau from the north. Their job was to gather any cattle they found. The British did not know the plateau was very long.

- The central column was led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Eyre. It had about 400 men, mostly infantry. They also had some cavalry and two rockets on mules. They were to cross the plateau and drive cattle through passes on its south side.

- The third column was led by Cathcart himself. It had about 400 men, including infantry, two cannons, and some cavalry. This column was to move along the west side of Berea. They would then meet the other columns in front of the mountain. This plan was meant to stop the Basuto from moving their cattle away.

The Battle Begins

At dawn on December 20, the British crossed the Caledon River. They started their push towards Thaba Bosiu. The Basuto were surprised by the British attack. They felt Cathcart had tricked them. The cattle near Thaba Bosiu were quickly moved away. Basuto infantry guarded them. The cavalry prepared for battle.

Napier's column crossed the Caledon. By 8 a.m., they could see the peak of Berea. After a short rest, they began gathering large herds of cattle on the mountain slopes. Meanwhile, Moshoeshoe's son Molapo had hidden 700 cavalry and several hundred infantry. They were above the Berea Mission Station.

At midday, Napier's force began moving 4,000 captured cattle and 55 horses. They were heading back to the Caledon camp. Then, Molapo's infantry attacked the back of the column. His cavalry charged the Lancers. A group of 30 Lancers rode into a dry riverbed. They did not know it ended in a rocky ridge. Basuto cavalry trapped them there. They killed 27 Lancers and wounded one with battle axes and assegais. Another group of British cavalry was cut off near the mission station. Five of them were shot dead. Napier gathered his soldiers and pushed back Molapo's warriors. Two more Basuto attacks were stopped by a Lancer charge and rifle fire. Napier's column then returned to the Caledon camp.

Cathcart's and Eyre's columns started at 3 a.m. They moved together downstream. They were shot at from a small hill but suffered no injuries. They reached Khoabane village at 6 a.m. This village was about 1.5 miles west of the Berea Mission Station. There, they separated. Cathcart moved west to go around the mountain. Eyre continued straight.

Eyre ordered some of his soldiers to capture a position above Khoabane. The British fought their way through difficult land. They exchanged fire with the Basuto. One British soldier was killed. Several Basuto warriors and a few civilian women were also killed by accident. More fighting happened at a village on a hilltop, which the British set on fire.

Eyre's column saw a herd of 30,000 cattle. But they struggled to control the animals because most of the soldiers were on foot. By 1 p.m., they had only captured 1,500 animals. At the same time, 300 of Molapo's horsemen suddenly attacked them. These horsemen were armed with the lances of the British soldiers they had killed. They were even wearing British caps. Eyre's hat was knocked off by a knobkerrie. The British lost four soldiers killed and 10 wounded. A captured British officer, Captain Walter Faunce, was killed. This was in revenge for the earlier killing of civilians. The Basuto were eventually driven off by rifle and rocket fire. They left at 4 p.m. when heavy rain started.

Cathcart's column had gone around the south-western side of Berea. Cannon fire made groups of Basuto horsemen flee. This allowed the British to take over a small hill. It overlooked the Phuthiatsana valley, about 3 km from Thaba Bosiu, by midday. The Basuto slowly gathered in front of and to the right of the British. They circled the British position. Sometimes they came close enough to shoot with muskets. But they were always driven away by British fire. Their numbers grew to 6,000 cavalry. They were led by Moshoeshoe and his sons Letsie, Sekhonyana, and Masopha.

Eyre's column left Berea and joined Cathcart at 5 p.m., just as the rain stopped. The combined British force moved back about 2 km down the road. They secured the cattle Eyre had captured in a nearby kraal (a traditional enclosure for livestock). The Basuto fought more intensely. Masopha, Sekhonyana, and Moshoeshoe's brother Lelosa led cavalry charges. The British fired rifles and canister shot (a type of cannon ammunition). The Basuto were surprised by how disciplined the British were. They saw them roasting meat in their camp. The Basuto returned to Thaba Bosiu around 8 p.m. Cathcart stayed alert. He did not let his men unroll their blankets for sleep.

What Happened Next

The British had gathered over 5,000 cattle and many other animals. The Basuto thought they had lost. Letsie urged his father to ask for peace. Others suggested retreating to the Maloti Mountains. Cathcart also did not expect the Basuto to fight so hard. His soldiers were tired and low on ammunition. There was also some confusion about the British plan. The decision was made to go back to the Caledon camp. They would continue the fight later.

At midnight, Moshoeshoe wrote a letter to Cathcart. A French missionary named Eugène Casalis translated it into English. In the letter, Moshoeshoe asked for peace. He also ordered his troops to stop attacking. The next morning, the Basuto found that the British had already left Berea. The letter had not been sent yet.

A few hours after the British returned to their camp, a Basuto messenger delivered the letter. He carried a flag of truce (a white flag showing he came in peace). Cathcart believed that another attack on Thaba Bosiu could lead to a much bigger war. He did not want that. So, he ignored his officers' arguments and accepted the truce. He invited Moshoeshoe to Platberg.

The captured cattle and wounded soldiers were sent to Bloemfontein. The British army began leaving Basutoland on December 24. Moshoeshoe's people did not let him travel. So, a British official named Charles Owen visited Thaba Bosiu instead. Masopha and Sekhonyana helped Owen find and bury the bodies of 20 British soldiers.

The Basuto paid back 3,500 cattle. Of these, 1,500 were given to tribes they had raided. The rest were sold, and the money went to Boer farmers. The value of the sold cattle was much less than the £20,000 Cathcart wanted. But he decided to drop any further claims.

The Basuto thought they had lost about 20 killed and 20 injured. Cathcart reported that the Basuto probably lost between 500 and 600 men. Today, experts believe Basuto casualties were fewer than 50. British casualties were 38 killed and 14 wounded.

In 1855, the British soldiers who fought in the Battle of Berea received a medal. It was called the South African General Service Medal. The Basuto were very impressed by the British soldiers. They remember the battle as Ntoa ea Masole, which means "Battle of the Soldiers."

Moshoeshoe was now able to convince his people to stop raiding Boer farmers. Trade between the two nations started again. Relations between the British and Basuto remained friendly. This helped the Basuto avoid being destroyed during the Free State–Basotho Wars in the 1860s. Instead, they became a British dominion (a self-governing territory).

One part of the Berea plateau is now known as the Lancers Gap. There is a story that the 12th Lancers rode off a cliff there and died.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |