Battle of Camp Hill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Camp Hill (Battle of Birmingham) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

Prince Rupert shown attacking "Brimidgham", from the Parliamentarian pamphlet A True Relation of Prince Ruperts Barbarous Cruelty against the Towne of Brumingham |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Prince Rupert | Captain Richard Greaves | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200 foot 1,200 horse |

300 foot Militia |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c.30 | 15 men 1-2 women 40 prisoners More than 340 homeless |

||||||

The Battle of Camp Hill (also known as the Battle of Birmingham) happened on Easter Monday, 3 April 1643. It took place in and around Camp Hill, Warwickshire, during the First English Civil War. In this fight, about 300 Parliamentarian soldiers from Lichfield and local townspeople tried to stop a larger force. This force was made up of 1,400 Royalists led by Prince Rupert. They wanted to pass through Birmingham, which was a town that supported Parliament but had no strong defenses.

The Parliamentarians fought back surprisingly well. Royalists said people shot at them from houses as the small Parliamentarian force was pushed out of town. To stop the shooting, the Royalists set fire to houses where they thought the shots came from. After the battle, the Royalists spent the rest of the day looting the town. The next morning, before leaving, they burned even more houses. Burning and looting an undefended town as punishment was common in Europe at the time. However, it was unusual in England. The Royalists' actions in Camp Hill gave the Parliamentarians a strong reason to criticize them.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

At the start of the Civil War, the area around Birmingham, known as the Black Country, was important. It was one of the few places in England that could make weapons and supplies. King Charles I badly needed these supplies. He didn't have access to major weapon stores like those in Portsmouth and Hull. But Worcestershire, near Birmingham, could provide swords, pikes, guns, and cannon shot.

Shot came from Stourbridge and Dudley. Many small workshops in the county made sword blades and pike heads. It's said that a skilled sword maker named Robert Porter refused to sell swords to King Charles I. This made the King very angry. However, the Royalists had Colonel Dud Dudley. He had found a way to make iron using coal. He claimed he could make all kinds of iron for weapons more cheaply and quickly.

In October 1642, King Charles I marched through Birmingham on his way to the Battle of Edgehill. The townspeople seized some of his carriages. These contained royal belongings, which they sent to Warwick Castle, a Parliamentarian stronghold. During the first year of the war, Birmingham's people also captured Royalist messengers and small groups. They sent them as prisoners to Coventry, a fortified city. This is where the saying "send him to Coventry" comes from.

Historian John Willis-Bund noted that King Charles I often sought small acts of revenge. So, Prince Rupert was ordered to punish Birmingham for its disloyalty. This was especially for the insults they showed the King in October 1642. A historian named Clarendon described Birmingham as a town famous for its strong disloyalty to the King.

Rupert's mission had three goals:

- Punish Birmingham.

- Set up a military base in Lichfield.

- Clear the surrounding area of Parliamentarian support.

For this, he had a force of 1,200 horsemen and dragoons, and 600 or 700 foot soldiers.

On 3 April, Rupert marched from Henley-in-Arden to Birmingham. Clarendon noted that Birmingham was not officially a military base for Parliament. It was hard to fortify because of how it was built. Yet, the townspeople had built small defenses at both ends of the town. They also blocked off other areas. They promised not to let any of the King's forces enter.

Rupert found these defenses when he arrived. The road into Birmingham was blocked by earthworks. The people of Birmingham had a small force to defend these works. There was a small company of foot soldiers under Captain Richard Greaves. The Lichfield military base had also sent a troop of horsemen. But their total strength was only about 200 men. Rupert didn't think such a large force like his would be stopped by so few. He sent his Quarter-Master ahead to arrange lodging. He wanted to assure the townspeople they wouldn't be harmed if they acted peacefully. But they didn't trust him. They refused to let him into the town. From their small defenses, they fired shots at him.

The Battle Begins

It was about three in the afternoon when Rupert was surprised to find that the townspeople were determined to fight. Many Parliamentarian leaders, both military and civilian, thought it was a bad idea. But the "middle and lower class" people, especially those with weapons, insisted on fighting. So, they all decided to resist.

Seeing this, Rupert ordered an immediate attack on their defenses. These defenses were just earth banks with a few musketeers behind them. As the Royalists advanced, they faced heavy gunfire. They couldn't hold their ground and had to retreat. A second attack also failed.

Things were getting serious. Rupert couldn't afford to be defeated by the people of Birmingham. A direct attack seemed unlikely to succeed. Some of Rupert's men realized they could go across the fields. They could ride around the defenses and attack the defenders from behind. This plan worked. The defenders couldn't fight attacks from both the front and the rear. They left their defenses and ran into the town. Rupert's soldiers followed them.

From the houses, scattered shots were fired at the Royalist soldiers as they moved up the street. In response, the soldiers set fire to the houses from which they were shot. Soon, the town was burning in several places. As the Royalists pushed on, resistance weakened. Those who had fought fled and scattered.

However, the fight wasn't completely over. Captain Richard Greaves gathered his horse troop. He lined them up at the far end of the town, towards Lichfield. He then turned them around and charged the scattered Royalists. The Royalists, not expecting any more resistance, gave way. Lord Denbigh, who was leading them, was badly wounded. He was knocked off his horse and left for dead. He died five days later from his injuries. His men fled back in confusion until they reached their own main forces. They then regrouped behind the Royalist lines.

Greaves had achieved his goal. His charge bought time for his foot soldiers to escape and prevented them from being chased. He didn't push his success further. He himself had received five wounds during his charge. He regrouped his men and moved towards Lichfield. He had saved his soldiers, but he left the townspeople to the Royalists.

Rupert's men were angry because of the resistance and Greaves' charge. They were not merciful. They rode around the town, jumping over hedges and ditches to catch the townspeople. Those they caught were killed. Reports suggest that tradesmen, laborers, and even women were killed without distinction.

Aftermath

Rupert did not stay long in Birmingham. On Easter Tuesday, 4 April, he marched from Birmingham to Walsall. On Wednesday, he reached Cannock. He stayed there until Saturday, 8 April. Then he marched to Lichfield and began to attack the town.

The Battlefield Today

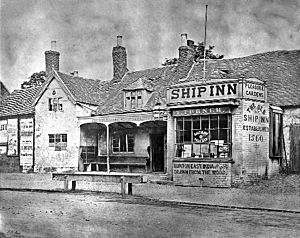

Today, the area where the battle took place has been developed into a city. There are no physical signs of the battle left. The site of Birmingham's earth defenses is now a road. Prince Rupert's headquarters, which local stories say was the "Old Ship" public house, survived into the 1800s. It is only preserved in photographs now.

Reports from the Time

Accounts written during and after the Civil War show strong feelings about the battle. Clarendon, a Royalist historian, wrote that Rupert did not punish the town as much as they deserved. He said they paid a smaller fine than expected, considering their wealth and actions. Clarendon also tried to explain the death of a clergyman. He claimed the clergyman was killed after refusing to surrender and insulting the King.

Clarendon added that if it weren't for the death of Lord Denbigh, he wouldn't have mentioned this battle. He regretted that important Royalist figures often died in battles, while Parliamentarians rarely lost men of high standing. Lord Denbigh's death was significant because his son, Basil Fielding, strongly supported Parliament. This meant the family's influence shifted from the King to Parliament.

Parliamentary supporters praised Birmingham's bravery and criticized the Royalists' cruelty in burning houses. Royalist supporters, however, celebrated the punishment given to the disloyal town.

Three main accounts of the fight were published:

- The first was a Parliamentarian account published on 3 April 1643. It was titled True Relation of Prince Rvpert's Barbarous Cruelty against the Towne of Brumingham. This pamphlet described how Rupert's forces attacked Birmingham, burned houses, and killed people. It claimed many important Royalist commanders were killed, including the Earl of Denbigh. This pamphlet included reports signed by "R. P." (possibly Robert Porter, the sword-cutler) and "R. G." (possibly Richard Greaves).

- The second account, dated 14 April 1643, was a Royalist pamphlet: A Letter written from Walshall by a worthy Gentleman to his Friend in Oxford, concerning Burmingham. This defended Rupert from accusations of cruelty. It claimed that only a few houses were burned during the attack. It also stated that Rupert ordered fires to be put out, and any other fires were started by soldiers against his orders after he left.

- The third account, dated 1 May 1643, was a strong Parliamentarian report: Prince Rupert's Burning love of England, discovered in Birmingham's Flames. This detailed Birmingham's suffering under Rupert's forces. It described how the town was attacked, looted, and burned. It also listed the number of houses burned and people left homeless. This report was published to show the kingdom what to expect if the Royalists were not stopped.

Historian John Bund noted that these titles clearly show Parliament's complaints against Rupert. They were upset by his victory over Birmingham. But they were even more upset by his use of harsh war rules against undefended towns. For a long time after, Parliamentarians continued to speak strongly about the "Birmingham Butcheries."

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |