Battle of Langnes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Langnes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Swedish–Norwegian War of 1814 | |||||||

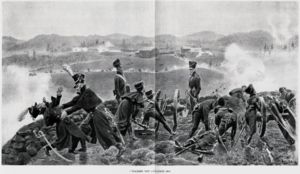

The entrenchments at Langnes, by Andreas Bloch |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 8 guns |

3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 killed 10 wounded 2 guns lost |

60–100 killed or wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Langnes was an important fight between Norway and Sweden on August 9, 1814. It was part of the Swedish-Norwegian War of 1814. Even though the battle didn't have a clear winner, it was a smart move for the Norwegians. It helped them avoid having to give up completely to the Swedish forces.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Norwegian army had been losing battles against the Swedish forces in Eastern Norway. When the Fredrikstad Fortress surrendered on August 4, it seemed like Sweden would soon win the war.

At this time, Norwegian soldiers in the Smaalenenes Amt area were trying to get organized again. They were east of Askim, near the Glomma river. To help their troops retreat faster, they built a special bridge called a pontoon bridge at Langnes. This bridge was designed so that the area around it, called the bridgehead, would be easy to defend if the Swedes attacked.

Getting Ready for the Fight

Colonel Diderich Hegermann was in charge of the Norwegian forces at Langnes. He set up his soldiers to protect the bridgehead. This allowed other Norwegian troops to cross the bridge safely. He had two regiments and three groups of sharpshooters. He also had eight cannons. Four of these cannons were placed on a small hill to fire at the Swedish attackers.

Meanwhile, the Swedish forces were marching towards Langnes. They were led by General Eberhard von Vegesack and Lieutenant Colonel Bror Cederström. They sent out small groups to check the area. The first Swedish troops arrived at Langnes during the night of August 9.

Colonel Hegermann had also sent out Norwegian patrols to keep an eye on the Swedes. There were small fights between the two sides during the night. The weather was very bad, with lots of rain. One Norwegian Captain even survived a close call because a Swedish scout's gun wouldn't fire due to the wet weather. The Captain fought bravely, broke his sword, but managed to defeat the Swedish soldier and take his gun. This captured gun is now in the Norwegian Museum of Defence.

The Battle Begins

Norwegian Surprise Attack

Colonel Hegermann decided to use the bad weather to his advantage. Before the sun came up, he launched a surprise attack on the Swedish troops. In the dark and rain, the fight quickly became a close-up struggle with bayonets and gun butts. The Norwegians pushed the tired Swedes back. However, Hegermann wasn't sure how many Swedish soldiers were coming. He worried his troops might get cut off. So, he ordered them to retreat back to their strong defensive position, called an entrenchment, as morning arrived. The Swedes followed closely behind.

The Swedish Attacks

As dawn broke, two Swedish battalions attacked the Norwegian entrenchment. They charged from a small hill, about half a kilometer away from the Norwegian lines. This area is where Langnes Station is today. The open fields between the hill and the Norwegian cannons were perfect for the Norwegian artillery. The ground was muddy from the night's rain, which slowed down the Swedish advance.

Colonel Hegermann told his soldiers to wait until the Swedes were very close before firing. This allowed the cannons to shoot into the side of the Swedish column with special canister shots. These shots were like giant shotgun blasts. Hegermann later said that the cannon fire made it look like "a wagon had rolled through them from head to queue."

The first Swedish attack was very costly for them. Most of their soldiers who died in the battle were lost during this first charge. Some Swedish soldiers tried to hide at the Langnes farm, but Norwegian cannon fire drove them away and destroyed the buildings.

The Swedes regrouped and attacked a second time through the rain and mud. Again, they were met with heavy fire and couldn't break through the Norwegian lines.

Later that morning, the Swedes attacked a third time. This time, they spread out in a "skirmisher" formation. This made it harder for the Norwegian cannons to hit them. The Swedes also had better gunpowder, which meant their muskets could shoot farther. This attack was very damaging to the Norwegian cannon battery, which was on a small hill without good protection. Swedish riflemen shot at the Norwegian artillery soldiers, killing several, including Lieutenant Hauch. Colonel Hegermann quickly reorganized the battery and drove the sharpshooters away with well-aimed cannon shots. Even though the cannons were effective, the Norwegian commanders realized their battery was in a bad spot and couldn't hold off the Swedes forever.

Norwegian Withdrawal

The young king, Christian Frederik, had been staying at a nearby farm. He was woken by the sound of the cannons. When he rushed to the pontoon bridge, he saw soldiers carrying the body of Lieutenant Hauch. The king reportedly said, "Too much blood for my sake!" But the soldiers replied, "Not too much, my Liege, too little!" However, considering the bigger picture of the war, the king ordered a retreat. Colonel Hegermann wanted to counterattack, and they argued. The king is said to have asked, "But by God, have you not sacrificed enough of these fair folks' blood?"

The Norwegians had very few losses behind their defenses: only 6 soldiers died (including Lieutenant Hauch) and 9 or 10 were wounded. The two Swedish battalions had at least 15 dead and 47 wounded. The Swedes felt they had succeeded because they pushed back the initial Norwegian attack and checked the fields.

Around noon on August 9, 1814, the last shots of this major battle between Norway and Sweden faded away. With the Swedes no longer a threat, the Norwegian army crossed the makeshift bridge without problems. Since they didn't have enough horses, the Norwegians decided to drop three cannons into the deep Glomma river. The soldiers protested, but the cannons were lost. Then, the bridge was taken apart by cutting its ropes.

What Happened Next

After crossing the Glomma river, Colonel Hegermann moved his troops south. They went to strengthen other defenses along the river, which were now in danger because the Swedes had taken some islands. The experienced Swedish Crown Prince Charles John ordered his troops to secure the entire eastern side of the river. There were more small fights along the river until a final ceasefire was signed on August 14.

Even though the Norwegians held back the Swedes at Langnes, it was clear that Norway would eventually lose the war. The Norwegian army was running low on supplies and only had food for two more weeks. Before the battle, Crown Prince Charles John had offered to talk about peace. Even though the Norwegians fought well at Langnes, they lost the war five days later when King Christian Fredrik agreed to a ceasefire.

The talks that followed led to the Convention of Moss. This agreement started the process of creating a union between Sweden and Norway that lasted for a century. The Norwegian resistance at Langnes was not wasted. The army had safely retreated across the Glomma river and was still strong. The Swedes realized that a full military victory would be very costly for them. The victory at Langnes gave Norway enough power in the peace talks to avoid a complete surrender.

As a secret part of the treaty, the young king had to call a special meeting of the Storting (Norway's parliament). Then, he had to give up his throne and go back to Denmark. He later became king of Denmark in 1848. The Storting then changed the Norwegian Constitution to allow Norway to join a "personal union" with Sweden. This meant they would share a king but keep their own laws and government. On November 4, 1814, the Storting approved the new Constitution and elected King Charles XIII of Sweden as the King of Norway. This created the Union between Sweden and Norway.

Norway managed to keep its independence in this loose union. It had its own Constitution, its own separate government, and its own laws. Only the king and foreign policy were shared with Sweden. This setup laid the groundwork for Norway to fully break away from the union in 1905.