Battle of Sant Esteve d'en Bas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Sant Esteve d'en Bas |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nine Years' War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Urbain Le Clerc de Juigné (DOW) | Ramon de Sala i Saçala | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,300 regular infantry | 650 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,086 killed or captured | 7 killed and 5 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Sant Esteve d'en Bas happened on March 10, 1695, in Catalonia, Spain. This battle was part of the Nine Years' War. It was a fight between French soldiers led by Brigadier Urbain Le Clerc de Juigné and Catalan militia fighters, known as miquelets, along with armed villagers.

The French army was on a mission to punish the village of Sant Esteve d'en Bas. The people there had refused to pay money to the French army. However, the Catalan militia, led by Ramon de Sala i Saçala, attacked the French. The French force was almost completely defeated in two different fights.

The first and bloodier fight took place near the Malatosquera wood and the Sant Roc bridge. The French lost 500 men who were either killed or hurt. After this defeat, Juigné and his remaining troops ran to Olot. They tried to hide inside a convent. But the Catalans forced the French to give up by setting the building on fire.

The Catalans won with very few losses: only 7 men killed and 5 wounded. In contrast, the French lost 260 soldiers killed and 826 were taken prisoner. Juigné was among those captured. This French defeat was followed a month later by Spanish troops and miquelets surrounding the French bases at Castellfollit and Hostalric. The French decided to destroy and leave these positions in July because they couldn't hold them.

Why the Battle Happened

Catalonia was an important area during the Nine Years' War. At first, the Spanish army in Catalonia faced problems. They didn't have enough supplies and had a difficult relationship with the local people. This was partly because of a past rebellion called the Revolt of the Barretinas.

The French army, led by the Duke of Noailles, also had limited resources. For the first four years of the war, both sides mostly tried to wear each other down slowly. In 1694, the French King Louis XIV sent more resources to his army in Catalonia. With these new supplies, Noailles managed to break through Spanish defenses. His army won the battle of Torroella and captured important cities like Girona and ports like Roses.

By 1695, the French found that people in the areas they controlled were not willing to pay money to support the army. These villagers started to fight back in an organized way. For example, during the winter of 1694-1695, people in Calella fought off 800 to 1,000 French soldiers. They killed between 60 and 100 of them.

French troops were also constantly bothered by Catalan militia forces called miquelets. These fighters would set up surprise attacks from woods and high places. One of the best miquelet leaders was Captain Ramon de Sala i Saçala, a local official from Vic. He won two victories against the French that winter. In December, he attacked a French supply convoy, killing 25 soldiers and capturing 25 more. On February 24, he defeated a group of French dragoons (soldiers on horseback) at Navata, killing 7 and capturing 28 soldiers and 32 horses.

Sant Esteve d'en Bas was one of the villages that refused to pay the French. Even after a French group looted the village as punishment, the people still refused. On December 28, 700 French soldiers were sent to arrest the village leaders. But they found the village empty and looted it again, taking two priests as hostages.

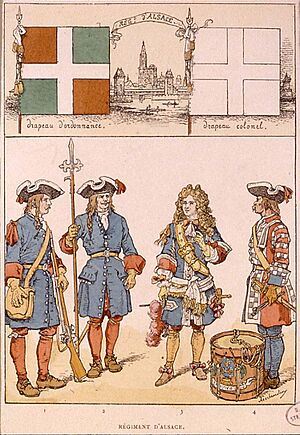

In March 1695, the villagers were still rebellious. So, Monsieur de Saint-Sylvestre, the French governor of Girona, ordered Brigadier Juigné to punish the village for a third time. Juigné was the commander of the Castellfollit base. He led 1,300 skilled soldiers from his own base and others in Figueres, Banyoles, and Besalú. These soldiers came from famous regiments like the German Alsace, Swiss Manuel, Swiss Schellenberg, and French Royal-Artillery. A famous French writer, Philippe de Courcillon, even called them "some of the best soldiers in that area."

The Battle Begins

The French force left Castellfollit on the evening of March 9. They passed by Olot and spent the night near the Fluvià river. At dawn, some local farmers and miquelets spotted them and sent a warning to Sant Esteve d'en Bas. The women and children of the village went to hide in the mountains. The men prepared to fight the French.

They also called for help from Ramon de Sala i Saçala. He was in the nearby village of Sant Feliu de Pallerols, gathering men for new miquelet companies with Captains Josep Mas de Roda and Pere Baliart i Teula.

Meanwhile, Juigné reached the Bas valley. He left some soldiers behind at El Mallol and took positions on the Puigpardines hill. From there, he sent a third of his force to burn Sant Esteve. The French troops had burned 16 buildings when Ramon de Sala arrived with 8 companies of miquelets. Pere Baliart led 8 other companies. They forced the French to run back to Juigné's position.

At Puigpardines hill, Juigné was already being attacked by 80 armed local villagers (called 'somatent'). When Sala's, Mas', and Baliart's miquelets arrived, Juigné decided to retreat. But when they tried to cross the Fluvià river again, they found their way blocked.

Juigné then decided to try and escape to Olot by going through the Malatosquera wood and over the Sant Roc bridge. But the Catalans were quicker. Sala split his miquelets into two groups of 300 men each. Josep Mas de Roda led the first group, chasing and attacking the French through the wood. Sala himself blocked the Sant Roc bridge with the second group. During the running fight in the woods, Juigné's force lost 25 men and left behind some of their ammunition.

Despite the attacks, the French managed to take control of the bridge and started to cross the Fluvià river. However, the miquelets and armed villagers fired at them from the south, killing up to 70 French soldiers. A French military historian from that time, Charles Sevin de Quincy, said that Juigné's group managed to retreat to Olot in good order. But a local Catalan historian from the 1800s, Esteve Paluzie i Cantalozella, claimed that the French troops ran away in a messy way. He said they left 150 prisoners for the Catalans, who took them to Sant Esteve d'en Bas under heavy guard.

When they reached Olot, most of Juigné's force went inside the El Carme convent. About 90 Swiss soldiers from the rear group hid inside the village hospital. The Swiss soldiers quickly gave up. But the main French group, with Juigné, held out for two hours. The miquelets and villagers surrounded the building and managed to make a hole in its walls. However, they were pushed back in a close-quarters fight, losing two men killed and one wounded.

Sala's men then broke through the wall of a chapel and attacked the convent again. But the French were tightly packed inside, so this attack was also pushed back. Sala ordered his men to set the building's gates on fire. But the French blocked the gap with stones and bricks. The Catalans finally got inside by setting large amounts of pitch (a sticky, tar-like substance) and sulfur on fire at the two holes they had made. The fire and smoke blinded and choked the French soldiers, who retreated to the convent's cloister (an open area inside). After this, Juigné, who was badly wounded, asked to surrender.

What Happened Next

The French soldiers gave up after being promised that their officers would not be stripped of their belongings. However, all of them became prisoners of war and had to give their weapons and money to the Catalans. Juigné, along with 136 other wounded soldiers and a German captain, stayed in Olot for medical care. But he died shortly after.

The French lost 251 or 260 men killed (including 32 officers) and 826 were taken prisoner. The miquelets only lost 7 men killed and 5 wounded. These numbers are well known because René Desgrigny, a French official in Girona, wrote a letter to Olot's leaders asking for the number and rank of the prisoners. He wanted to exchange them later. In this letter, Desgrigny noted that Monsieur Juigné was lucky to be dead, as the defeat would have likely caused him serious trouble. The 690 French prisoners who were not hurt were first taken to Vic and then to Barcelona. They arrived in Barcelona on March 15. A large crowd and the Spanish Viceroy, the Marquis of Gastañaga, watched their arrival.

In the weeks after the battle, Spanish troops and local militia put more pressure on the French soldiers at Castellfollit. On April 5, the Catalan miquelets, helped by five companies of dragoons and several villagers, defeated a group of French troops. They killed 60 soldiers and took 200 prisoners.

Noailles, who was sick at the time, ordered Lieutenant-general Saint-Sylvestre to gather supplies for Castellfollit. He sent these supplies with an escort of 2,000 foot soldiers and 600 cavalry. A group of miquelets, Spanish dragoons, and villagers led by Blai de Trinxeria attacked and defeated this supply convoy on April 15. After that, the French bases at Castellfollit and Hostalric were effectively surrounded.

On May 19, Saint-Sylvestre gathered an army of 8,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 cavalry and managed to get supplies to Hostalric. But Castellfollit remained surrounded. Noailles and his second-in-command did not get along well. Saint-Sylvestre wanted to destroy and abandon both Hostalric and Castellfollit, but Noailles did not want to give up any land.

In late June, King Louis XIV replaced Noailles with Louis Joseph, Duke of Vendôme. Noailles accused Saint-Sylvestre of being bad at his job and, like other high officers, of stealing from the country. This, he said, had made the local people turn against the French army.

On July 8, Vendôme led his troops to Castellfollit. The French soldiers there had forced the local people out and had eaten horses and mules. Their numbers were also lower because soldiers had left. The situation was impossible to maintain, so Vendôme came to evacuate the soldiers and destroy the fortress. After that, the French army went to Hostalric and destroyed its defenses too. They returned to Girona on July 28.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de San Esteban de Bas para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de San Esteban de Bas para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |