Revolt of the Barretinas facts for kids

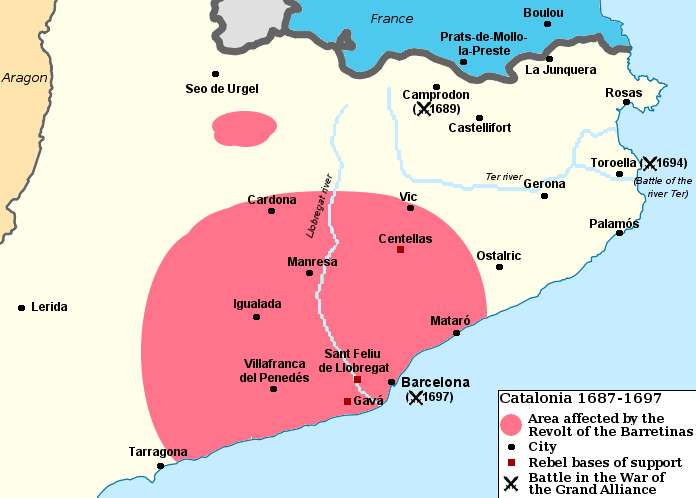

The Revolt of the Barretines (also called the Revolt of the Gorretes) was a big uprising in Catalonia, a region in Spain. It happened between 1687 and 1689. People were upset with the government of King Charles II of Spain. The main reason for the revolt was that soldiers were forced to live in people's homes. People also protested against high taxes and felt strong Catalan pride. France helped fund and encourage the rebellion as part of a larger war called the War of the Grand Alliance.

Most of the people who supported the revolt lived in the countryside, especially poor farmers. Some wealthy people from the countryside also joined. However, people in the city of Barcelona, like merchants and thinkers, and the local government did not support the rebellion.

Contents

Why the Revolt Started

For a long time, there had been disagreements between the Spanish government (mostly controlled by Castile) and the people in the lands of the Crown of Aragon. This included Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia, and Majorca. Even though the crowns of Aragon and Castile had the same king since 1517 (King Charles I), they kept their own laws and ways of governing.

People had rebelled before, like in the Reapers' War from 1640 to 1652. That earlier revolt had wide support in Catalonia. As a result, France took over a part of Catalonia called Roussillon. But after that war, Catalans started to feel differently about France. France began to seem more like a business rival than a helpful friend.

Over time, the leaders in Catalonia and the Spanish King got along a bit better. The Spanish government was quite forgiving after the 1640 revolt. Many regional leaders could have been punished severely, but they were not. This made people appreciate the leniency.

King Charles II became king in the 1660s. Many historians think he was not a very effective ruler. But in Catalonia, his lack of action was seen as a good thing. Instead of trying to control everything from Madrid, King Charles II let regions handle their own business. John of Austria the Younger was a popular leader in Catalonia who gave important jobs to Catalan nobles. This made the nobles happy. A key Catalan noble, Feliu de la Peña, even called Charles II "the best king Spain ever had."

However, in 1684, many Catalan farmers faced hard times. Swarms of locusts destroyed crops, which hurt farmers and the whole economy. The locust problem continued for several years, and it was especially bad in 1687.

Soldiers Living in Homes

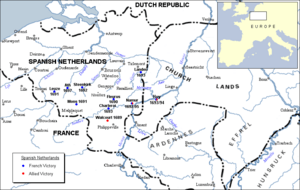

Spain and France were not friendly in the 1680s. From 1683 to 1684, France defeated Spain in a war. The French King Louis XIV was trying to expand his empire. Spain then joined an alliance called the League of Augsburg to protect itself from France.

Fearing another war with France, the Spanish government sent soldiers to Catalonia in 1687 to guard the border. There were about 2,400 soldiers. However, the forts and barracks were in bad shape and could not house all of them. So, most soldiers had to live in people's private homes. People also had to pay a "military contribution" (a tax) to support these soldiers.

The terrible harvest of 1687, along with already low food supplies, made many people in the countryside desperate. Farmers protested, asking for the soldiers to leave. Three members of the Diputació del General (Catalonia's highest government body) sent these complaints to King Charles II. But the leader of Catalonia, the Marquis of Leganés, responded by arresting these three officials.

Things got worse on October 7, 1687, in a town called Centelles. People there were already unhappy with their local count. Then, a soldier hit a woman during an argument over a chicken. The woman quickly gathered the townspeople to protest. The soldiers left the town to calm things down, but people's anger kept growing. Many towns decided to let the soldiers stay but refused to pay the military tax to support them.

Another fight between soldiers and citizens happened on April 4, 1688, in Villamayor. In response, a group of farmers marched to Mataró, an important port town, and entered it on April 6. They rang church bells and gathered the people, shouting "Long live the land!" They forced the town's leaders to support their cause.

The group grew to about 18,000 people and marched towards Barcelona, the capital city. They demanded a pardon for their actions, a lower military tax, the release of the three arrested officials, and the release of another official named Pedro Llosas. By April 12, the government agreed to all their demands. The farmers had plenty of supplies from the countryside, and Barcelona depended on them for food. Once their demands were met, the farmers went back home.

Anger Spreads

The upper classes were worried by this sudden uprising. The government feared that Barcelona could be taken over at any moment. To prevent the farmers from returning, the three imprisoned officials were released on May 10. The leader of Catalonia, finding the situation too stressful, left his job. He was replaced by the Count of Melgar.

Fights between soldiers and farmers continued, and the government's control over the countryside became very weak. Even after the government made some promises, people now wanted to be free from all government demands and refused to pay taxes. About 800 "segadors" (reapers, the name rebel farmers used) marched on Puigcerdà. They demanded that no one should work unless they earned a minimum wage of 4 reales. This idea spread to other towns.

Church leaders also got into arguments with citizens over tithes (church taxes), leading to a riot on June 13. On June 14, rioters opened a weapons storage building and armed the citizens. The next day, June 15, was a holiday, so the rioters relaxed. This gave soldiers a chance to sneak into the armory and stop the growing revolt. Four popular leaders were hanged on July 5, and four more on August 9. Still, many small uprisings happened across Catalonia. Even Barcelona had riots. Most of these small revolts were against wealthy Catalans who were exempt from the military tax, or against unpopular citizens like bankers and tax collectors.

In December 1688, Catalonia's leader changed again. The Count of Melgar retired and was replaced by the Duke of Villahermosa. The situation in Europe was getting worse, and a war with France seemed certain. Catalonia's defenses needed to be prepared. Funding was still a problem. In March 1689, the new leader tried to get a "voluntary donation" to rebuild defenses and support the soldiers. Barcelona's ruling council and the Catalan Estates approved this. The leader hoped it would be better received if it had local approval.

But this did not work. Catalan farmers saw the donation as just another new tax. This donation showed a big difference between social classes. Higher classes were exempt from the donation, which kept them mostly happy. This was different from the 1640 revolt, where almost everyone in Catalonia had protested Spanish taxes.

French Help and Open Rebellion

Leaders of the "segadors" had been talking with French agents even before the "voluntary donation" was announced. The donation gave France a good way to encourage protests against soldiers and taxes to become a real rebellion. France sent money to print flyers that spoke against the donation and the Spanish government.

France had taken the Catalan-speaking region of Roussillon during the 1640 Catalan Revolt. Some families had members on both sides of the border. These connections were useful. A noble named Sieur Gabriel Gervais, who was related to rebel Joseph Rocafort, helped send money and supplies across the mountains. Ramón de Trobat, a French official in Roussillon, wrote strong articles and got rebel leaders like Rocafort and Enric Torras to promise loyalty to France.

With the countryside angry at the government, the donation failed. The leader of Catalonia stopped it. Some historians believe that if the French had invaded in April 1689, they could have easily taken over all of Catalonia. However, the French were more careful. They took the forts of Camprodon on the border on May 22 and stopped there. Perhaps they did not realize how successful their agents had been, or they were more focused on the war in Germany. The flyers continued to cause unrest, but without a full invasion, no major uprising happened. The French left Camprodon in June, and the Spanish army took back and destroyed their own fortress.

Official records show no more incidents until October 1689. That month, Joan Castelló, from Centelles, was arrested for telling farmers not to pay the donation. Under questioning, he named Enric Torras and others. He was then executed. In November, some soldiers were attacked by farmers and forced to give up their weapons and horses. The farmers did not try to kill them, just disarm them. This trend spread quickly, with disarmed soldiers encouraged to return to Barcelona. This started the phase of protests that became closest to a real rebellion.

To stop the situation, the leader of Catalonia decided to punish the rebels. He sent a force of 800 cavalry, 500 infantry, and 2 cannons to destroy Sant Feliu de Llobregat. In response, the farmer militia cut off Barcelona's water supply. They were driven away, but now the "segadors" were fully armed. A large farmer militia, calling itself the "Army of the Land" and numbering about 8,000, marched on Barcelona again, just like a year earlier.

This time, the leader of Catalonia fought the farmers. The farmers won the first battle because they had more people. But they did not do as well in three later battles as the leader's troops kept attacking them.

Elsewhere, other groups rebelled, but the soldiers in the villages fought back. These punishments stopped the movement from growing. About 2,000 "segadors" attacked Mataró, but the leader's troops defeated them. Forty rebels were killed, and six were forced to work as rowers on galleys (ships). Other clashes happened at Castellfollit de la Roca and Sarrià. On November 30, 1689, the farmer militia surrounding Barcelona, tired of constant attacks, broke up and went back to the countryside.

Anton Soler, a wealthy country gentleman who had led the rebels, was killed by his own adopted son for the reward the government offered. Soler's head was taken to Barcelona and displayed in a cage on the wall of the Generalitat (the main government building).

Small incidents continued in 1690 and 1691, but the rebellion never got strong again after Soler's death and the end of the Barcelona siege. The quick and harsh punishments, along with the offer of a general pardon for those who stopped fighting, helped calm the people. Good harvests in 1688 and 1689 made paying taxes easier. Radical Catalan nationalist flyers continued to be spread by Trobat, but they had less effect.

In 1690, the leader of Catalonia wrote that rebels were still a threat near Centelles, but they only controlled the mountains. The French tried to convince officials in the Duchy of Cardona to rebel if the French army came close, but this never happened. The plan was discovered in December 1691, and the Cardona plotters were hanged. A very small number of "segadors" joined the French army, perhaps fleeing punishment. By 1695, there were fewer than 90 of them.

In 1694, under French direction, there was an attempted uprising in Sant Feliu de Llobregat and the fort of Corbera. Later, in August, there was a riot in Tarragona led by a group called "The Poor." None of these rebellions succeeded. The actual French army was more threatening, but by 1694, many Catalans saw them as unwanted invaders. The French had also angered Barcelona by bombing the city from the sea on July 10, 1691.

The government rewarded Barcelona's loyalty by allowing its councilors to keep their hats on when meeting the king. The Diputació was also given the titles "Most Illustrious" and "Most Faithful." These symbolic gestures were very important at the time. Local Catalan fighters called Miquelets helped the Spanish army drive the French out of Catalonia. The French had some early successes but were eventually forced to retreat.

What Happened Next

The main result of the Revolt of the Barretines was a lasting dislike of France among Catalan leaders and thinkers. This became important ten years later, in 1700, when King Charles II died without a son. Charles's death led to the War of the Spanish Succession.

There were two people who claimed the throne: the French Philip, Duke of Anjou and the Austrian Emperor Leopold I. The Spanish government chose Philip. The French King Louis XIV, Philip's grandfather, naturally supported his grandson. But the Catalan upper classes, still not trusting France after its attempts to stir up the farmers against them in 1689, did not like Philip. They saw him as "a king chosen by Castilians."

In 1702, the Catalan parliament voted to recognize Leopold as king. A full rebellion against Philip began in 1705 when Austrian troops arrived to help. The war continued for nine more years, until the Siege of Barcelona in 1714. This is when the last Catalan supporters of Leopold were defeated by the combined French and Castilian army.

The Nueva Planta decrees, issued by Philip from 1707 to 1714, ended the separate laws and governments that Aragon and Catalonia had kept. Castilian law and institutions were made mandatory throughout Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Revuelta de los Barretines para niños

In Spanish: Revuelta de los Barretines para niños

- Second Brotherhood, a similar revolt in Valencia in 1693