Battle of Solomon's Fork facts for kids

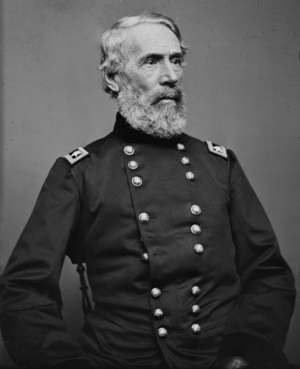

The Battle of Solomon’s Fork was a short but important fight that happened on July 9, 1857. Even though the main battle only lasted one day, the chase for the Cheyenne warriors, led by Colonel Edwin 'Bull' Sumner, went on for several weeks. Sumner and his 300 cavalry troops had been traveling since May 1857, making their journey much longer than the battle itself.

Historians today have different ideas about how important this battle was. Some believe it was a key moment in the long history of conflicts between the U.S. Army and Native American tribes. Others see it as just one small part of the U.S. government's efforts to take over Native lands.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

For many years before the Battle of Solomon's Fork, the Cheyenne people lived mostly in peace with white settlers. The settlers had not yet started moving into Cheyenne lands. The Cheyenne nation had about 3,000 members, including 900 warriors. While they were peaceful with white settlers, they sometimes had conflicts with other Native tribes.

The Cheyenne people valued a strong fighting spirit, especially among their young men. Dying bravely in battle was seen as a great honor. Living to old age without having fought was not as respected.

Trouble started after a conflict in 1854 where Sioux people fought with U.S. soldiers. In March 1856, Colonel William Selby Harney met with Sioux leaders at Fort Pierre. Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders were also there. Harney demanded that all tribes make peace with each other and leave the Platte River area. He warned them of serious consequences if they did not agree.

The Cheyenne agreed to avoid conflict with the U.S. Army. However, several events soon made this agreement difficult to keep. Accusations of theft by U.S. soldiers, small fights where people on both sides were hurt or killed, and intimidating actions by U.S. troops caused a lot of tension and distrust.

The Cheyenne later attacked settler wagon trains. This was in response to a U.S. troop attack that had killed ten Cheyenne people and injured eight. These attacks on wagon trains led to the deaths of twelve white settlers and the kidnapping of two. General Persifor E. Smith, who was in charge of the Department of the West, demanded strong punishment for the Cheyenne attacks. At the time, the U.S. Army was busy trying to keep peace between groups supporting and opposing slavery in Kansas. So, Smith suggested delaying the operation against the Cheyenne until the next year. The Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, agreed.

The Long Journey to Kansas

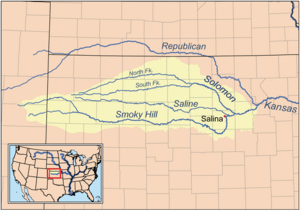

In May 1857, Colonel 'Bull' Sumner began his march from Fort Leavenworth. He led 300 soldiers from four cavalry units and some Pawnee scouts. Another group, led by Major John Sedgwick, took a different route south with 40 wagons and five Delaware scouts. Sumner's path was planned to go to the west bank of the Platte and North Platte rivers, which was known Cheyenne territory.

In early June, Sumner's group faced their first big challenge. The river was very high and cold because of heavy snowmelt from winter. When the 300 men and their horses tried to cross, several men and horses drowned.

After the river crossing, the company traveled through a hot and dry plain. Wagon Master Percival G. Lowe described it as "thirty miles across…the hottest place this side of the Dives, and…about as dry."

On June 30, the group came across what was usually a small stream but was now a 100-yard-wide swamp. The troops had to build a dirt road around the swamp because they didn't want to lose more men or horses to drowning. Eventually, Sumner realized that his two guides didn't know where the other group of troops, led by Sedgwick, was supposed to meet them.

While the U.S. troops were struggling with the journey, the Cheyenne people were getting ready for war. During a buffalo hunt, two groups of Cheyenne discovered that the U.S. Army was looking for them. They decided to stay together for safety and prepare for an attack. Soon, the Delaware and Pawnee scouts found fresh Native tracks. They led Sumner and 50 of his men, without supplies, straight to the Cheyenne camp. About 300 Cheyenne warriors were lined up and ready for battle.

The Battle Begins

Before the battle, Cheyenne medicine men performed special protection rituals for their warriors. They made the warriors believe that bullets would not harm them. Because of this belief, the Cheyenne calmly waited for Sumner and his small group.

Sumner and his smaller army decided to attack that afternoon, even though most of his soldiers and cannons were still far behind. Sumner and his troops pulled out their sabers (swords) and charged forward when he gave the command. They did not use their guns. When the Cheyenne warriors saw swords instead of firearms, many of them lost their confidence in being protected.

During the confusion of the battle, many soldiers and Native warriors ended up fighting hand-to-hand. Many Cheyenne fled to the north bank of the Saline River, where their camp was, to join more Cheyenne warriors. The troops and Cheyenne broke into smaller fights spread out over about five miles. One notable fight involved Lieutenant James E.B. Stuart. Stuart went to help a fellow Lieutenant and friend and was shot by a Native who took his gun. Stuart survived and later became a famous Cavalry Commander in the American Civil War.

By the end of the battle, two U.S. soldiers were killed and eight were wounded. On the Cheyenne side, nine were killed, though the Cheyenne reported only four warriors dead. The battle itself lasted only one day. Sumner soon received orders to send most of his cavalry to protect a Mormon expedition heading to Salt Lake City.

What Happened After

Even though the U.S. Army technically won this battle, it did not bring peace to the Great Plains.

Historians still debate how important this battle was. However, it is considered the first major battle between the United States and the Cheyenne people. This attack marked the beginning of a long period of intense conflict between the United States and the Cheyenne. Many skirmishes and battles followed, such as the Fort Robinson Massacre and the Sand Creek Massacre. These events left many Northern Cheyenne starving, scattered, and constantly on the run from the U.S. military. The movement of the Northern Cheyenne away from their Southern relatives led to the loss of many tribal members. This was a difficult topic for many Cheyenne to talk about for several generations.

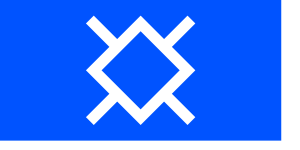

Today, the Northern Cheyenne Reservation is located in southeastern Montana. It covers about 444,000 acres. The tribe has roughly 12,266 members, with about 6,012 of them living on the reservation.

Images for kids