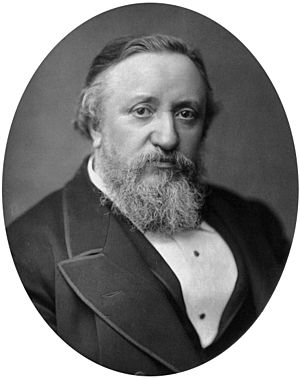

Benjamin Ward Richardson facts for kids

Sir Benjamin Ward Richardson (born October 28, 1828 – died November 21, 1896) was an important British doctor. He was a physician (a medical doctor), an anaesthetist (someone who helps patients sleep during surgery), and a physiologist (someone who studies how the body works). He was also a "sanitarian," meaning he worked to make public places cleaner and healthier. He wrote many books about medical history. He won important awards like the Fothergill gold medal in 1854.

Richardson was a good friend and colleague of John Snow, another famous doctor. When Snow died suddenly, Richardson helped finish and publish Snow's book about anaesthetics in 1858. Richardson believed strongly in Snow's ideas that tiny germs caused infectious diseases. He continued Snow's work on anaesthesia, which helps people feel no pain during operations. He introduced many new anaesthetics, like methylene bichloride. He also invented a special mouthpiece for giving chloroform. He helped make other important medicines known, such as amyl nitrite for chest pain. In 1893, he was made a knight for his great work helping people.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Richardson was born in Somerby, Leicestershire, England. He was the only son of Benjamin Richardson and Mary Ward. His mother wanted him to become a doctor. So, he was taught by a reverend and later became an apprentice to a surgeon named Henry Hudson.

In 1847, he started studying at Anderson's University (now the University of Strathclyde). But he got very sick with a fever while working at a hospital. This stopped his studies for a while. After recovering, he worked as an assistant to other doctors.

In 1854, he earned his M.A. and M.D. degrees from the University of St Andrews. He later became an important part of the university.

A Career in Medicine

In 1849, Richardson started working with Dr. Robert Willis, who was famous for editing the works of William Harvey. Richardson lived in Mortlake and joined a club where he met many famous writers and artists.

In 1850, Richardson became a licensed doctor with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. He later became a Fellow there in 1878. He also helped start the St Andrews Medical Graduates' Association and was its president for 35 years.

He became a member of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1856 and a Fellow in 1865. In 1867, he was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society. This is a very high honor for scientists.

Richardson moved to London in 1853. He worked as a doctor at several hospitals and dispensaries (places where people could get medical care). He was also a doctor for the "Newspaper Press Fund" and the "Royal Literary Fund," which helped writers.

In 1854, Richardson started teaching forensic medicine (medical law) and public hygiene (public health) at the Grosvenor Place School of Medicine. He was the dean of the school until 1865.

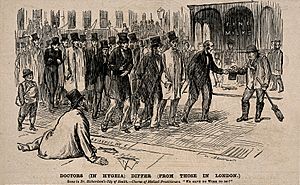

He was also the president of the health section of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science. In 1875, he gave a famous speech in Brighton about "Hygeia," which was his idea for a perfect healthy city.

In 1854, he won the Fothergillian prize for his essay on "Diseases of the Unborn Child." He became the president of the Medical Society of London in 1868.

Richardson was recognized internationally for his work. He became a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1863. In 1880, he joined the London School Board. In June 1893, he was knighted for his great work in helping people.

He was also the President of the Association of Public Sanitary Inspectors of Great Britain from 1890 to 1896. He worked hard to protect these inspectors. They often faced problems from local business owners whose interests were affected by health rules.

From 1884 to 1895, he published a regular medical journal called The Asclepiad. It shared new research and ideas in medicine.

Important Awards

In 1854, Richardson won the Fothergillian gold medal for his essay on "Diseases of the Foetus in Utero" (diseases of babies before they are born). In 1856, he won the Astley Cooper triennial prize for his essay on "The Coagulation of the Blood" (how blood clots).

His Legacy and Impact

Richardson died on November 21, 1896, in London. His body was cremated.

He was a big supporter of improving public health. He focused on small details in homes that could help people live longer. He spent many years trying to reduce pain for people by finding new ways to use anaesthesia. He also worked on more humane ways to slaughter animals. He introduced many anaesthetics, with methylene bichloride being one of the most famous. He also found a way to make a part of the body numb by freezing it with an ether spray.

Richardson was one of the first people to support bicycling. He wrote an article about "Cycling as an Intellectual Pursuit" in 1883. He also introduced many other important medical substances that doctors soon began to use widely.

He was a leader in the Bread Reform League, which wanted people to eat healthier whole-wheat bread. While he wasn't a strict vegetarian, he believed in humane treatment of animals. He worked to find ways to kill animals painlessly for meat.

Richardson was a very active writer. He wrote biographies, plays, poems, and songs, along with his scientific work. He created and edited the Journal of Public Health and Sanitary Review. He also wrote many articles for famous medical journals like The Lancet.

Family Life

On February 21, 1857, he married Mary J. Smith. They had two sons and one daughter who survived. His son Aubrey married Jerusha Davidson Richardson, a writer and helper of others.

His Books and Writings

Non-fiction Books

- (1858). The Cause of the Coagulation of the Blood.

- (1876). Diseases of Modern Life.

- (1876). Hygeia, a City of Health. (This book described his vision for a perfectly healthy city.)

- (1877). The Future of Sanitary Science.

- (1878). Health and Life.

- (1878). Total Abstinence.

- (1882). Dialogues on Drink.

- (1884). On the Healthy Manufacture of Bread.

- (1884). The Field of Disease.

- (1887). The Commonhealth.

- (1891). Foods for Man: Animal and Vegetable: A Comparison.

- (1896). Biological Experimentation: Its Function and Limits.

- (1897). Vita Medica: Chapters of a Medical Life and Work.

Selected Articles

- (1880). "Health Through Education," The Gentleman's Magazine.

- (1880). "Dress in Relation to Health," The Gentleman's Magazine.

- (1886). "Woman's Work in Creation," Longman's Magazine.

Other Writings

- (1889). "The Art of Embalming," in Wood's Medical and Surgical Monographs.

- (1895). "Introduction," to A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, by Frances Elizabeth Willard.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |