Bill T. Jones facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bill T. Jones

|

|

|---|---|

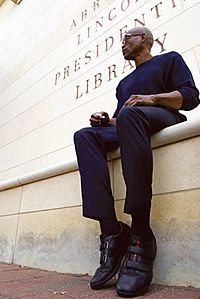

Jones in Springfield, Illinois

|

|

| Born |

William Tass Jones

February 15, 1952 |

| Education | Binghamton University |

| Occupation | Choreographer, dancer |

| Spouse(s) | Arnie Zane; Bjorn G. Amelan |

William Tass Jones, known as Bill T. Jones (born February 15, 1952), is a famous American choreographer, director, author, and dancer. He helped start the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. This company has its main home in Manhattan. Bill T. Jones is also the Artistic Director of New York Live Arts. This organization hosts dance shows, offers education programs, and helps artists.

Besides his work with New York Live Arts and his dance company, Jones has created dances for many big performing groups. He has also worked on Broadway shows and other plays. People often call him "one of the most notable, recognized modern-dance choreographers and directors of our time."

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Bill T. Jones was born in Bunnell, Florida. He was the tenth of 12 children. His parents, Estella and Augustus Jones, first worked on farms. Later, they worked in factories. In 1955, when Bill was three, his family moved to Wayland, New York.

In high school, Jones was a great track athlete. He also enjoyed drama and debate. After finishing high school in 1970, he went to Binghamton University. He got in through a special program for students from less fortunate backgrounds. At Binghamton, he started focusing on dance. Jones said that at Binghamton, he took his first classes in West African and African-Caribbean dancing. He loved it right away because it wasn't about competing. He also studied ballet and modern dance there.

A Career in Dance

Starting Out in Dance

In 1971, during his first year at Binghamton, Jones met Arnie Zane. Zane was a university graduate who was working on his photography skills. They became close friends and partners in both life and work. Their partnership lasted until Zane passed away in 1988.

About a year after meeting, Jones and Zane lived in Amsterdam, Netherlands, for a year. When they came back, they met dancer Lois Welk. She showed them "contact improvisation." This is a dance style where partners intertwine and shift their weight. In 1974, they formed American Dance Asylum (ADA) with Welk and another dancer, Jill Becker. ADA was a group that performed across the country and internationally. They also taught classes and hosted shows in Binghamton.

Jones created many solo dances during this time. He started performing in New York City in 1976. He performed at places like The Kitchen and Dance Theater Workshop. His dances often mixed elegant movements with spoken words. These words explored his memories and feelings about the dancing. They ranged from personal stories to thoughts on social issues.

In 1979, Jones and Zane decided to move on from ADA. They wanted to live in a place that supported their art and their identity as an interracial couple. They moved to the New York area in late 1979.

Jones was tall and graceful, while Zane was shorter and moved sharply. This difference, along with contact improvisation, became key to their dances. Their works combined Jones's love for movement and speech with Zane's eye for visuals. Their duets included film projections, singing, and spoken conversations. They often focused on political and social topics. They also openly showed their personal relationship, which was unusual for the time. A series of three duets, Blauvelt Mountain (1980), Monkey Run Road (1979), and Valley Cottage (1981), made them well-known choreographers.

The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

From the mid-1970s until 1981, Jones and Zane traveled the world performing duets. Jones also performed solos. In 1982, they officially started the Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Dance Company. They chose dancers who were unique and didn't fit traditional molds. These dancers had different body types, shapes, and skin colors.

Jones is known for challenging ideas through his choreography. He explores themes like identity, art, race, and social issues. His works like Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin/The Promised Land (1990) and Still/Here are some of his most thought-provoking pieces.

Exploring Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin

Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin/The Promised Land first showed in 1990. This was two years after Jones lost his partner, Arnie Zane. Throughout his career, Jones has used his feelings of being different from society to shape his dances. This work is a good example. Jones said this piece is about how performers, choreographers, and the audience can find common ground despite their differences.

The work has four parts. The first three parts explore Jones's and the dancers' personal stories. They connect these to bigger social histories using images and references. The last part looks at ideas of freedom, what "home" means, and finding commonality.

Act 1: The Cabin

This act reworks the story of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. It offers a new look at the character of Uncle Tom. Jones uses images from his own past to show violence and loss. He remembered stories his mother told him about punishment, which influenced the dance movements.

Act 2: Eliza's Journey

This act imagines what might have been true for Harriet Beecher Stowe's character, Eliza, if things were different. Jones explored these "what ifs" through movements and the dancers' identities. He created five "Elizas," each with unique movements. These movements showed the different feelings and desires of each version of the character. For example, one Eliza's movements referenced Jones's grandmother resting her hands on a hoe. Another Eliza showed anger with tight fists. A man danced the last Eliza, inviting the audience to think about identity. Jones used both big social problems and personal experiences to show the many possibilities for Stowe's Eliza.

Act 3: The Supper

Jones described this act as a conversation with his mother's religious beliefs. The image of the Last Supper was common in the homes where Jones grew up. He also saw it as a shared experience in many less wealthy homes. He broke down this image, showing all the questions it doesn't answer. The act ends with a rap about fairness.

Act 4: The Promise Land

The final section, The Promise Land, was very talked about when it first came out. It wasn't always performed. When it was, people from the local community joined the production. This section focuses on the human body as a way to show commonality among all people. This shared understanding isn't a final answer, but a feeling of peace. The work asks how many different groups and experiences can truly feel "free at last."

Still/Here and Its Discussion

While Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin/The Promised Land was a big and important work, the 1995 New York premiere of Still/Here caused a lot of discussion. Still/Here is about facing serious illnesses. It uses video clips of people talking about their experiences with diseases like cancer. It also has special music, spoken words, and dance.

This work made people ask if art should be about social issues. Many critics liked the production, especially since many dancers had been affected by illnesses. Still/Here was well-received on its international tour in 1994. Newsweek magazine called it "a work so original and profound that its place among the landmarks of 20th-century dance seems ensured."

However, Arlene Croce, a dance critic for The New Yorker, wrote a very negative review. She disliked art that she felt presented artists as "victims." Croce refused to even see the production. She believed that politics were making art less about art itself.

Croce's article caused a big debate. The next issue of the New Yorker had many letters about it from famous cultural figures. Some disagreed strongly with Croce. For example, critic bell hooks said: "To write so contemptuously about a work one has not seen is an awesome flaunting of privilege." Other critics also questioned Croce's choice not to see the work. The debate grew and was discussed in national newspapers. Author Joyce Carol Oates wrote in The New York Times that the article raised important questions about art, fairness, and the role of politics in art. This discussion brought Bill T. Jones to wider attention. In 2016, Newsweek noted that Jones is "probably best known outside of dance circles for his 1994 work Still/Here."

Other Creative Partnerships

Bill T. Jones has created over 100 works for his own company. He has also choreographed for many other groups. These include Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Boston Ballet, and Lyon Opera Ballet. In 1995, Jones worked with Toni Morrison and Max Roach on a piece called Degga. In 1999, his collaboration with Jessye Norman, How! Do! We! Do!, premiered in New York.

In 1989, Bill T. Jones choreographed D-Man in the Waters. This was during a time when many people were affected by a serious health crisis. After a company member, Demian Acquavella, passed away, Bill T. Jones created this piece in his honor. The dance highlights Acquavella's absence to raise awareness about the challenges many faced. The piece features a lot of lifting, showing the unity Jones wanted to see in society. Men lift men, women lift women, and women lift men. D-Man in the Waters is a beautiful and moving artwork that uses movement to show the difficulties of the health crisis, the loss of those affected, and the strong desire to come together.

Jones has also directed and choreographed for operas. In 1990, he choreographed Sir Michael Tippett's New Year. He also helped create and direct Mother of Three Sons, performed in Munich and New York. Jones has also directed plays, including Dream on Monkey Mountain in 1994. He also worked with artist Keith Haring in 1982 on performance and visual art projects.

Broadway and Beyond

In 2005, Jones choreographed The Seven for the New York Theatre Workshop. This musical was based on an old Greek play but set in a modern city. It used different music styles to create a "hip-hop musical comedy-tragedy." The Seven won three Off-Broadway Lucille Lortel Awards, including one for Jones's choreography.

Jones was also the choreographer for the 2006 Broadway musical Spring Awakening. This play explores the feelings of teenagers. Spring Awakening was very popular and won eight 2007 Tony Awards. Jones received the 2007 Tony Award for Best Choreography.

Jones also helped create, direct, and choreograph the musical Fela!. This show ran off-Broadway in 2008 and opened on Broadway in 2009. It is based on the life of Nigerian musician and activist Fela Kuti. The Broadway show won three Tony Awards, including Best Choreography for Jones.

In 2010, he was honored at the Kennedy Center Honors. This is a special award for artists who have greatly contributed to American culture. In June 2019, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, Queerty named him one of the Pride50 "trailblazing individuals who actively ensure society remains moving towards equality, acceptance and dignity for all queer people".

Opera Work

In 2017, Jones directed and choreographed the first performance of We Shall Not Be Moved. This opera was commissioned by Opera Philadelphia. New York Times listed it as one of the best classical performances of 2017.

Personal Life

Bill T. Jones is married to Bjorn Amelan. Amelan grew up in Haifa, Israel, and in Europe. They have been together since 1993. Amelan is also the Creative Director for the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. He has designed many of the company's sets since the mid-1990s. Jones's work Analogy/Dora: Tramontane (2015) focuses on the experiences of Amelan's mother during World War II.

Jones and Amelan live in Rockland County, New York, just north of New York City. They live in a house Jones and Arnie Zane bought in 1980. Even though Jones has worked in New York City's arts scene for a long time, he has never lived in the city itself.

One of Jones's sisters, Rhodessa Jones, is a well-known performance artist in San Francisco. She also teaches arts in prisons. Jones's nephew, Lance Briggs, is the focus of two works by the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company: Analogy/Lance (2016) and Letter to My Nephew (2017). These works explore the challenges in Briggs's life.

Important Works

Jones has choreographed over 120 documented works. Here are some important ones, including collaborations with other artists and companies.

Works by Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane

- Pas de Deux for Two (1973)

- Across the Street (1975)

- Monkey Run Road (1979)

- Blauvelt Mountain (1980)

- Valley Cottage (1981)

- Rotary Action (2020)

- Intuitive Momentum (1983) (Music by Max Roach; set by Robert Longo)

- Secret Pastures (1984) (Set by Keith Haring; costumes by Willi Smith)

- The Animal Trilogy (1986)

- The History of Collage (1988)

Works by Bill T. Jones

- Everybody Works/All Beasts Count (1975)

- Holzer Duet... Truisms (1985) (Text by Jenny Holzer)

- Virgil Thomson Etudes (1986) (Costumes by Bill Katz & Louise Nevelson)

- D-Man in the Waters (1989)

- It Takes Two (1989)

- Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin/The Promised Land (1990)

- Absence (1990)

- Broken Wedding (1992)

- Still/Here (1994)

- We Set Out Early...Visibility Was Poor (1997)

- Black Suzanne (2002)

- Chapel/Chapter (2006)

- A Quarreling Pair (2006)

- Serenade/The Proposition (2008)

- Fondly Do We Hope...Fervently Do We Pray (2009)

- Story/Time (2014)

Commissioned Works and Collaborations

- Fever Swamp (1983) (Commissioned by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater)

- Mother of Three Sons (1991) (Commissioned by New York City Opera)

- Broken Wedding (1992) (Commissioned by Boston Ballet)

- Degga (1995) (Collaboration with Max Roach and Toni Morrison)

- 24 Images per Second (1995) (Commissioned by Lyon Opera Ballet)

- How! Do! We! Do! (1999) (Collaboration with Jessye Norman)

- Bill and Laurie: About Five Rounds (1996) (Collaboration with Laurie Anderson)

- A Rite (2013) (Collaboration with Anne Bogart/SITI Company)

Major Awards and Honors

- 1986, New York Dance and Performance "Bessie" Award, Freedom of Information (with Arnie Zane)

- 1989, New York Dance and Performance "Bessie" Award, D-Man in the Waters

- 1991, Dorothy B. Chandler Performing Arts Award

- 2001, New York Dance and Performance "Bessie" Award, The Breathing Show & The Table Project (with Bjorn Amelan)

- 2003, The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize

- 2005, Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award for Lifetime Achievement in Choreography

- 2005, The Wexner Prize

- 2006, Lucille Lortell Award, The Seven (Outstanding Choreography)

- 2007, New York Dance and Performance "Bessie" Award, Chapel/ Chapter

- 2007, Off-Broadway Theater "Obie" Award, Spring Awakening (Choreography)

- 2007, Tony Award, Spring Awakening (Best Choreography)

- 2007, United States Artists Fellowship

- 2008, The MacArthur Fellowship

- 2009, Lucille Lortell Award, Fela! (Outstanding Musical)

- 2010, Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, France

- 2010, Tony Award, Fela! (Best Choreography)

- 2010, Kennedy Center Honors

- 2011, The YoungArts Arison Award

- 2013, New York Dance and Performance "Bessie" Award, D-Man in the Waters (Outstanding Revival)

- 2013, The National Medal of Arts

- 2014, The Doris Duke Performing Artist Award

- 2014, Washington University International Humanities Prize

- 2018, The James Robert Brudner Memorial Prize at Yale University

Film Appearances

- 1986: The Kitchen Presents Two Moon July

- 1994: Black Is... Black Ain't

- 2001: Free to Dance

- 2004: Bill T. Jones: Dancing to the Promised Land

- 2008: The Black List: Volume One

- 2008: The Universe of Keith Haring

- 2008: Bill T Jones – Solos

- 2021: Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters

See also

- Freda Rosen

- LGBT culture in New York City

- List of LGBT people from New York City

- NYC Pride March

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |