Brook stickleback facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brook stickleback |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Culaea

Whitley, 1950

|

| Species: |

C. inconstans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Culaea inconstans (Kirtland, 1840)

|

|

The brook stickleback (Culaea inconstans) is a small freshwater fish found across the U.S. and Canada. It usually grows to about 2 inches (5 cm) long. This little fish lives in clear, cool streams and lakes. It eats tiny water bugs, algae, and insect larvae. Bigger fish like smallmouth bass and northern pike sometimes eat it. Brook sticklebacks are most active at dawn and sunset. During summer, males build nests from plants and protect the eggs. They often die after the breeding season, making them an "annual species." Even though they are not currently endangered, changes to their watery homes, like cutting down trees near rivers, can harm them.

Contents

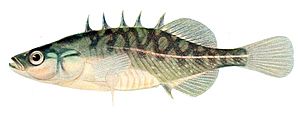

What Does a Brook Stickleback Look Like?

The brook stickleback has a body that gets thinner towards its tail. It has a slim part near its tail and a tail shaped like a fan. It looks a lot like the ninespine stickleback but has only five or sometimes six spines on its back. It also does not have bony plates along its sides.

Most of the year, this fish is grayish or olive green with some blurry spots. But during the time they lay eggs, the males turn almost black. Females get darker and lighter patches on their bodies. This species can grow up to 3 to 5 centimeters (1 to 2 inches) long.

Where Do Brook Sticklebacks Live?

The brook stickleback is a small fish, usually less than 8.7 centimeters (3.4 inches) long. It lives across the southern half of Canada and the northern part of the eastern United States. It is one of the smallest fish in these areas. Sometimes, you can find them in slightly salty water, but this is rare.

They live as far south as the Mississippi River and Great Lakes areas. You can also find them in states like Colorado and Nebraska in the west. In Canada, they are found in Alberta, Manitoba, and the Northwest Territory. While these are their natural homes, brook sticklebacks have also been introduced to other places. These include Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, parts of Utah, California, South Dakota, and Washington State.

Scientists have found that some populations in New Mexico might be native. In Nebraska, they are mostly found in small streams in the northern part of the state. They have been there since the early 1900s. Rivers like the Loup, Middle Platte, and Niobrara are home to many brook sticklebacks.

Even though they seem to be common, the Nature Conservancy says the species is "vulnerable." This might be because more dams are being built, especially in the eastern U.S. Dams can destroy their homes, fill waterways with dirt, change how nutrients move in streams, and damage their breeding areas. Changes in stream flow can also bring new predators.

How Brook Sticklebacks Live and Eat

Brook sticklebacks live in many different types of watery places. These include rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, and even hot springs. They can live in many habitats, but they prefer shallow areas less than 1.5 meters (5 feet) deep. These spots usually have lots of plants and slow-moving water. This is where they like to lay their eggs and raise their young. They can live from sea level up to about 2,400 meters (7,900 feet) high.

What Do Brook Sticklebacks Eat?

The brook stickleback is an omnivore, meaning it eats both plants and animals. They mainly eat insect larvae that live in water and adult insects that fall into the water. They also munch on tiny crustaceans, fish eggs, and even small snails. Sometimes, they eat plant material and algae.

Baby sticklebacks eat very small creatures because their mouths are tiny. As they grow bigger, adult sticklebacks can eat both small and larger organisms.

Who Eats Brook Sticklebacks?

Many animals prey on the brook stickleback, including large water insects, birds, mammals, and other fish. Because they are small, brook sticklebacks have special defenses. They have sharp spines and protective plates on their bodies to make it harder for predators to eat them. With these defenses and smart ways to avoid danger, they are not a main food source for most predators.

In studies, large water bugs and dragonfly nymphs could catch sticklebacks, but only at night. Fish are the most successful predators of the brook stickleback. Some fish that eat them include:

- Yellow perch

- Rock bass

- Creek chub

- Northern pike

- Smallmouth bass

- Largemouth bass

- Brook trout

- Rainbow trout

Brook stickleback eggs can also be eaten by other fish, including their own kind. Sometimes, brook sticklebacks compete with ninespine sticklebacks for food. However, ninespine sticklebacks usually live in open water, while brook sticklebacks prefer areas closer to the shore. If fathead minnows are around, brook sticklebacks might eat a wider variety of foods.

The Life of a Brook Stickleback

Brook sticklebacks usually lay their eggs in mid-summer. In spring, they swim upstream into smaller creeks and streams from rivers and lakes. They look for weedy areas to lay their eggs.

The male stickleback finds a safe spot and builds a nest. He uses algae, roots, and other water plants to build it. The nest has one entrance but no exit. When a female enters, she lays her eggs by shaking her body. Each shake helps more eggs come out. After all the eggs are laid, the female pushes through the side of the nest to get out. During this time, females sometimes make sounds. Scientists think this might attract other males to help fertilize the eggs.

After the eggs are laid, the male protects them. The eggs hatch in about 7 to 11 days. If the newly hatched babies wander away from the nest, the male gently scoops them into his mouth and puts them back inside. Egg-laying usually stops around mid-July because the water temperature changes quickly. The young eggs are very sensitive to these temperature changes.

These fish grow fast during their first summer. They usually become old enough to have their own babies by the next spring. Most adult brook sticklebacks die during or shortly after the egg-laying season. This is why they are called an "annual species," meaning they mostly live for about a year.

Protecting Brook Sticklebacks

The Nature Conservancy has listed the brook stickleback as "vulnerable." This means that while their numbers are not currently threatened, there is a chance their population could decrease. However, there are no specific plans just for protecting the brook stickleback right now.

This fish lives across most of the United States and Canada. This wide range means it could be affected by pollution in waterways. Brook sticklebacks live in many different places, from lakes to streams to sinkholes. This ability to live in various environments helps them handle different conditions. They can cope with some pollution, heavy metals, and cloudy water.

However, this does not mean they are safe from all human-caused changes. Their egg-laying season is short, and the eggs are very sensitive to temperature changes. Global temperatures are rising, which could change water temperatures everywhere. This could greatly affect when and how brook sticklebacks lay their eggs.

Protecting this species is important. Scientists have learned a lot about how new species form by studying brook sticklebacks.

How Can We Help Them?

One of the biggest reasons for the brook stickleback's success is its ability to spread to many places after the last ice age. They can be found from northern Canada all the way down to the southern U.S. Protecting these different locations is key for local ecosystems and for the species itself.

Current efforts to protect endangered fish species can also help the brook stickleback indirectly. Keeping certain invasive species out of lakes where brook sticklebacks live can protect them from new predators. Brook sticklebacks have good defenses like armored plates and spines against their usual predators. But invasive species with better hunting skills could seriously harm brook stickleback populations.

To help manage this species, scientists could use special nets to count how many fish are in certain areas. Taking samples every year would be helpful since they are an annual species. Tracking their numbers would help conservationists understand specific threats in different regions.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Culaea inconstans" in FishBase. October 2012 version.