Capitol Hill Occupied Protest facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Capitol Hill

|

|

|---|---|

| Capitol Hill Occupied Protest | |

CHOP on June 9, 2020

|

|

| Nickname(s):

CHOP or CHAZ

|

|

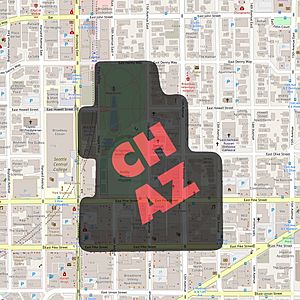

Area occupied by CHOP

|

|

| Designation | Self-declared autonomous zone |

| Established | June 8, 2020 |

| Disbanded | July 1, 2020 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Consensus decision-making, with daily meeting of protesters |

The Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP), also known as the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, was a special area in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, Washington. It was first called Free Capitol Hill and later the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ). This area was set up by people who were protesting the death of George Floyd in May 2020.

The CHOP started on June 8, 2020, and was cleared by police on July 1, 2020. It began after some tense moments between protesters and police. On June 7, a person drove a car towards a crowd and shot a protester. Police used things like tear gas and pepper spray in the area. The police reported that protesters were throwing objects and shining lasers. The next day, the police left their East Precinct building to help calm things down. Protesters then moved into the area, set up barricades, and called it "Free Capitol Hill." Later, it was renamed the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP).

The CHOP was a self-organized space with no official leaders. Police were not allowed inside. Protesters wanted to change how Seattle's police budget was used. They wanted more money to go to community programs, especially in Black communities. People in the CHOP created a large "Black Lives Matter" mural on the street. They also showed free movies and played live music. A "No Cop Co-op" offered free food and supplies. There were areas for public speakers and discussions, and a community garden was built.

The size of the CHOP got smaller over time. On June 28, the mayor met with protesters and said the city planned to remove most barricades. The police chief, Carmen Best, said the situation was "dangerous and unacceptable." On July 1, Seattle police cleared the area and took back their station. Protests continued in Seattle even after the CHOP was cleared.

Contents

History of the Protest

Why it Started

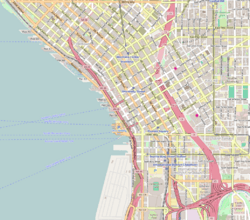

Capitol Hill is a busy neighborhood in Seattle, known for its diverse communities and lively nightlife. The Seattle Police Department had faced protests before. Since 2012, the department was watched by the federal government because it had been found to use too much force and show unfair actions.

Seattle has a history of large protests, like the 1999 WTO protests. The city also has cultural places created from past protests.

Protests about the death of George Floyd and unfair police actions began in Seattle on May 29, 2020. There were clashes in Seattle for nine days involving protesters and different police groups.

What Happened After

Street protests continued after the CHOP area was cleared. Vandalism was reported in Capitol Hill on July 19. Fireworks were thrown into the East Precinct, causing a small fire. The mother of Lorenzo Anderson, who died in a shooting near the CHOP, sued the city. She said the police and fire department did not protect her son.

On July 23, a group returned to Capitol Hill and damaged some businesses. On July 25, thousands of protesters gathered in Capitol Hill to support protests in Portland, Oregon. Federal agents were sent to Seattle, which made some residents uneasy. A march on July 25 was first peaceful but later became a riot. Businesses were damaged, and fires were started. Many people were arrested, and police officers were hurt.

In August, The New York Times reported that many businesses were still boarded up. Carmen Best, the police chief, resigned after the Seattle City Council voted to reduce the police department's size. Public discussions began about what to do with the art and garden left in the CHOP area.

In December 2020, people resisted attempts to clear Cal Anderson Park again. Protesters created barriers and occupied a private building.

Some business owners sued the city in 2020 for damages during the protests. A judge found that city officials had deleted many text messages about how they handled the CHOP. In 2022, the city settled a lawsuit for $200,000 and agreed to improve how it keeps records.

The CHOP Area

The CHOP area was first around the East Precinct building. Barricades were set up on Pine Street to block cars. The area included Cal Anderson Park, which was already active with protesters. It stretched north to East Denny Way, east to 12th Avenue, south to East Pike, and west to Broadway. Signs at the entrance read "You Are Entering Free Capitol Hill" or "Welcome to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone." The police station sign was changed to "Seattle People's Department."

On June 16, city officials and protest organizers agreed on a smaller area. The city installed concrete barriers to make the area safer and allow businesses to get deliveries. The new layout was shared by the mayor, saying the city wanted to keep a space for community and protest.

On June 17, a large tent camp was set up on 11th Avenue, and half of Cal Anderson Park became a big tent area with a community garden. The borders of the CHOP changed daily and became smaller over time. By June 24, the area had "shrunk considerably." Protesters focused more on the East Precinct building.

On June 30, police removed some barricades and moved others closer to the East Precinct. Notices were posted that Cal Anderson Park would close for cleaning, but the garden and art would stay. The remaining area was cleared by police on July 1, and Cal Anderson Park was closed for repairs.

Life and Activities in CHOP

Services Provided

Protesters set up the No Cop Co-op on June 9. It offered free water, hand sanitizer, and snacks donated by the community. Stalls provided vegan food, and others collected donations for people experiencing homelessness. Tents were set up near the former police station. Two medical stations offered basic health care. The city provided portable toilets and waste removal. They also offered fire and rescue services. The public health department offered COVID-19 testing in Cal Anderson Park for a while.

Some local restaurants saw more walk-up business, but many businesses in the zone closed.

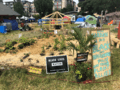

Community Gardens

Vegetable gardens appeared by June 11 in Cal Anderson Park. Activists started growing different foods from seedlings. The gardens were started by Marcus Henderson, a Seattle resident. Activists expanded the gardens, which were cared for by and for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). Signs honored Black farmers and remembered victims of police violence. Henderson's gardening group, Black Star Farmers, continued their work after the CHOP ended. He asked supporters to help keep the garden as the Black Lives Memorial Garden. This effort succeeded for a time. However, in October 2023, the Seattle Parks & Recreation Department announced plans to remove the garden. The department, with police support, removed the garden on December 27, 2023.

Arts and Culture

The intersection of 12th and Pine became a square for discussions and organizing. An area at 11th and Pine was a "Decolonization Conversation Café" for daily talks. An outdoor cinema was set up on June 9, showing films like 13th and Paris Is Burning.

The Marshall Law Band, a Seattle hip-hop group, performed for protesters. They played even when there was tear gas or rubber bullets. They continued playing regularly after the CHOP was set up. In November 2020, they released an album called 12th & Pine about their experiences.

A large mural was painted on East Pine Street on June 10 and 11. Local artists of color painted the letters, using supplies bought with donations.

Memorials

Visitors lit candles and left flowers at three memorials. These memorials had photos and notes for George Floyd and other victims of police actions.

| Person | Reason for Memorial | Type of Memorial | What it Looked Like |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charleena Lyles | Died from police action | Mural | Spray paint and plywood |

| George Floyd | Died from police action | Mural, Memorial | Spray paint and plywood |

| Lorenzo Anderson | Died in a shooting near the CHOP | Memorial | Flowers and balloons |

On June 19, events like a "grief ritual" and a dance party were held to celebrate Juneteenth.

How the CHOP was Run

People in the CHOP made decisions together through daily meetings and discussion groups. They did not have official leaders.

Protesters held frequent meetings to plan their actions. Seattle officials said there was no evidence of antifa groups organizing in the zone. However, some small business owners blamed antifa for scaring away their customers. Police Chief Carmen Best said on June 15, "There is no cop-free zone in the city of Seattle," meaning officers would enter if there were threats to safety. The New York Times reported in August that police generally did not respond to calls in the zone.

Some false information spread about the CHOP's leadership. A journalist shared a video of hip-hop artist Raz Simone handing a rifle to another protester. This happened because of rumors that a right-wing group might cause trouble. CNN later called Simone the zone's "de facto leader," which he denied. Simone was in contact with the Seattle Fire Chief during his time in CHOP. He left the area around July 15.

Names for the Area

The protest area had several names. "Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone" (CHAZ) and "Free Capitol Hill" were common at first. By its second week, it was more often called the "Capitol Hill Organized Protest" (CHOP).

On June 13, protest leaders agreed to change the name from CHAZ to CHOP. This change was made to focus less on "occupation" and be more accurate. The "O" in CHOP was changed to "Organized" to reflect that Seattle itself is an "occupation" of native land. Many news outlets reported on this name change.

Demands of the Protesters

The protesters had three main demands:

- Reduce city police funding by 50%.

- Use those funds for community efforts, like restorative justice and health care.

- Ensure that protesters would not be charged with crimes.

An early list of 30 demands, released on June 9, included the idea of ending the Seattle Police Department and prisons.

On June 10, about 1,000 protesters marched into Seattle City Hall asking for the mayor to resign.

Safety and Security

Protesters allowed people to openly carry firearms for safety. Members of the Puget Sound John Brown Gun Club (PSJBGC), an anti-fascist and anti-racist group, were seen carrying rifles on June 9. This was in response to rumors of an attack by a right-wing group. Even though the mayor had banned weapons in the area, this ban was not always enforced. The Washington Post reported on June 12 that PSJBGC was there without visible weapons.

Some businesses in the area hired private security companies. These companies had armed staff patrolling the zone. Volunteers also formed a group to provide security, focusing on calming down situations and preventing damage.

Outside Threats

Protesters were aware of threats from far-right groups like Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys. On June 15, armed members of the Proud Boys appeared in the zone. They wanted to challenge what they called protesters' "authoritarian behavior." Videos of these clashes became widely shared online.

A Proud Boys member, Tusitala "Tiny" Toese, was filmed punching a man and breaking his phone on June 15. Toese was known for fighting in the Pacific Northwest. He was later arrested for breaking his probation because of the video evidence from the CHOP.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Zona Autónoma de Capitol Hill para niños

In Spanish: Zona Autónoma de Capitol Hill para niños