Charles I of Anjou facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charles I |

|

|---|---|

Head from portrait statue by Arnolfo di Cambio, c. 1277

|

|

| King of Sicily Contested by Peter I from 1282 |

|

| Reign | 1266–1282 (island of Sicily and mainland territories) 1282–1285 (mainland territories, also known as the Kingdom of Naples) |

| Coronation | 5 January 1266 |

| Predecessor | Manfred |

| Successor |

|

| Count of Anjou and Maine | |

| Reign | 1246–1285 |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Count of Provence | |

| Reign | 1246–1285 |

| Predecessor | Beatrice |

| Successor | Charles II |

| King of Albania | |

| Reign | February 1272 - 1285 |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Prince of Achaea | |

| Reign | 1278–1285 |

| Predecessor | William |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Born | Early 1226/1227 |

| Died | 7 January 1285 (aged 57–59) Foggia, Kingdom of Naples |

| Burial | Naples Cathedral |

| Spouse | |

| Issue More |

|

| House | Capet (by birth) Anjou-Sicily (founder) |

| Father | Louis VIII of France |

| Mother | Blanche of Castile |

Charles I (born 1226 or 1227, died 1285) was a powerful French prince. He was also known as Charles of Anjou. He started a new royal family line called the Capetian House of Anjou.

Charles ruled many lands during his life. He was the Count of Provence and Forcalquier (in what is now France) from 1246 to 1285. He also became Count of Anjou and Maine in France. Most importantly, he was the King of Sicily from 1266 to 1285. This kingdom included the island of Sicily and southern Italy. He also became King of Albania in 1272 and Prince of Achaea in 1278.

Charles was the youngest son of Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile. He was first expected to join the Church. But he gained Provence through his marriage to Beatrice of Provence. He often argued with his mother-in-law and local nobles as he tried to take more control. His brother, Louis IX of France, gave him Anjou and Maine. Charles also joined Louis IX on a big journey called the Seventh Crusade to Egypt.

After returning, Charles made three rich cities in Provence—Marseille, Arles, and Avignon—accept his rule. He also helped a countess in Flanders, which led to him gaining more land. In 1263, the Pope asked Charles to take over the Kingdom of Sicily. This kingdom was ruled by the Hohenstaufens, whom the Pope disliked. The Pope even declared a crusade against the current ruler, Manfred, King of Sicily.

Charles was crowned king in Rome in 1266. He quickly defeated Manfred's army and took over Sicily and southern Italy. His rule became even stronger after he defeated Manfred's young nephew, Conradin, in 1268. Charles also joined the Eighth Crusade in 1270. He forced the ruler of Tunis to pay him a yearly tribute. Charles became very influential among the Pope's allies in Italy. However, his power worried the popes. They tried to guide his ambitions towards other areas.

In 1281, the Pope allowed Charles to plan a crusade against the Byzantine Empire. But a big rebellion called the Sicilian Vespers broke out in 1282. This rebellion ended Charles's rule on the island of Sicily. He managed to keep control of the mainland parts, which became known as the Kingdom of Naples. Charles died in 1285 while planning to invade Sicily again.

Contents

Early Life and Rise to Power

Growing Up as a Prince

Charles was the youngest child of King Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile. He was likely born in early 1227. He was the only son born after his father became king, which he often mentioned. He was also the first French prince named after the famous Charlemagne.

King Louis VIII died in 1226. His oldest son, Louis IX of France, became the new king. Louis VIII wanted his younger sons to have careers in the Church. We don't know much about Charles's early schooling. But he received a good education. He was very interested in poetry, medicine, and law.

Charles later said his mother, Blanche, greatly influenced his education. However, Blanche was busy running the country. So she probably had little time for her youngest children. Charles lived with his brother, Robert I, Count of Artois, from 1237. Later, he was cared for by his youngest brother, Alphonse, Count of Poitiers. In 1242, Charles joined his brothers in a military fight. This showed he was no longer going to be a churchman.

Gaining Provence and Anjou

In 1245, Raymond Berengar V, the Count of Provence, died. He left Provence and Forcalquier to his youngest daughter, Beatrice of Provence. This made her three older sisters, including Louis IX's wife Margaret, upset. They felt they had been unfairly treated. Their mother, Beatrice of Savoy, also claimed rights to Provence.

Many rulers wanted to marry Beatrice. But her mother put her under the Pope's protection. Louis IX and his wife Margaret suggested that Beatrice marry Charles. The Pope agreed to this plan. Charles quickly went to Aix-en-Provence with an army. He married Beatrice on January 31, 1246. Provence was part of the Holy Roman Empire, but Charles never swore loyalty to the Emperor. He started checking the counts' rights and income. This angered his new subjects and his mother-in-law.

Charles had not received any land from his father because he was a younger son. But in 1246, Louis IX made Charles a knight. Three months later, he gave Charles Anjou and Maine. Charles rarely visited these lands. He appointed officials to manage them for him.

While Charles was away, three rich cities in Provence—Marseille, Arles, and Avignon—rebelled. Charles's mother-in-law supported these rebels. Charles could not deal with them right away. He was about to join his brother's crusade. To calm his mother-in-law, he agreed to her right to rule Forcalquier. He also gave her a third of his income from Provence.

Joining the Seventh Crusade

In 1244, King Louis IX decided to lead a crusade. His three brothers, including Charles, also joined. They left France in 1248. After staying in Cyprus for months, they invaded Egypt in 1249. They captured Damietta and planned to attack Cairo. During their advance, Charles showed great bravery. He saved many crusaders' lives.

Charles's brother, Robert of Artois, died fighting the Egyptians. Charles and his other two brothers survived. But they had to give up the campaign. They were captured by the Egyptians in April 1250. The Egyptians released them in exchange for a large sum of money and the city of Damietta. On their way to Acre, Charles angered Louis by gambling. Louis was still sad about Robert's death. Louis stayed in the Holy Land, but Charles returned to France in October 1250.

Expanding His Power

Dealing with Rebellions

Charles's officials continued to check his rights and income in Provence. This caused a new rebellion while he was away. When he returned, he used both talks and military force. In 1250, the Archbishop of Arles and the Bishop of Digne gave their worldly rights in their towns to Charles. Charles also got military help from his brother, Alphonse. Arles surrendered in April 1251. Avignon accepted their joint rule in May. A month later, another rebel leader also gave up. Marseille was the last city to resist. But it also sought peace in July 1252. Its citizens accepted Charles as their lord. But they kept their own self-governing bodies.

Charles's officials kept looking into his rights. They visited every town and held public meetings. Charles introduced a salt monopoly, meaning only he could sell salt. By the late 1250s, salt trade made up about half of his government's income. Charles also removed local taxes. He encouraged shipbuilding and grain trade. He ordered new coins to be made for local use.

In 1250, Emperor Frederick II died. He was also the ruler of Sicily. The Pope claimed that Sicily now belonged to the Church. The Pope offered Sicily to Charles. But Charles's brother, Louis IX, told him not to accept. Louis thought Frederick's son was the rightful ruler. So Charles refused the offer in 1253. The Pope then offered Sicily to another English prince.

Queen Blanche, who had ruled France while Louis was on crusade, died in 1252. Louis made Alphonse and Charles co-rulers so he could stay in the Holy Land. Meanwhile, Margaret II, the Countess of Flanders, had problems with her son. She needed help to free her captured sons. She promised Hainaut to Charles. Charles accepted and invaded Hainaut. Most local nobles swore loyalty to him. But Louis IX insisted that his earlier decision about Hainaut be followed. In 1255, Louis ordered Charles to give Hainaut back to Margaret. But Margaret had to pay Charles a large sum of money over 13 years.

Charles returned to Provence, which was restless again. His mother-in-law still supported the rebels. But Louis IX convinced her to give Forcalquier back to Charles. She also gave up her other claims for a payment from Charles and a pension from Louis. In Marseille, Charles's supporters took control. All political power went to his officials. Charles continued to expand his power in the next four years. He gained lands in the Lower Alps. He also became the regent of the Kingdom of Arles. Many towns in Italy, like Cuneo, Alba, and Savigliano, asked for his protection. Their rulers also swore loyalty to him.

In 1258, Manfred, Frederick II's son, was crowned king of Sicily. The Pope was determined to end Manfred's rule. He sent an envoy to Paris to offer the Sicilian throne to Charles again. Charles met with the Pope's envoy in 1262.

While Charles was away, a new revolt started in Provence. The people of Marseille kicked out Charles's officials. But another nobleman stopped the rebellion from spreading. Charles gave up some land to Genoa to keep them neutral. He defeated the rebels and sent their leader away. With the help of the King of Aragon, Charles made peace with Marseille. Its walls were torn down, and people gave up their weapons. But the town kept its independence.

Conquering the Kingdom of Sicily

In 1263, Louis IX decided to support Charles's military campaign in Italy. The Pope promised to declare a crusade against Manfred. Charles promised not to take any other offices in Italian towns. Manfred tried to take control of Rome. But the Pope's allies elected Charles as the head of Rome's government. Charles accepted this. Some church leaders asked the Pope to cancel the agreement with Charles. But the Pope needed Charles's help against Manfred.

In 1264, two cardinals were sent to France to get support for the crusade. Charles sent troops to Rome to protect the Pope. Charles's sister-in-law promised not to act against him while he was away. French and Provençal church leaders also offered money for the crusade. The Pope died before the final agreement. Charles prepared for his campaign against Sicily. He made deals to secure his army's path through Italy. He also had the leaders of the Provençal rebels executed.

A new Pope was elected in 1265. He confirmed Charles's position in Rome. He urged Charles to come to Rome. Charles agreed to rule Sicily as the Pope's vassal. He would pay a yearly tribute of gold. He also promised never to seek the title of Emperor. Charles left Marseille in May and arrived in Italy ten days later. He was installed as head of Rome's government in June. A week later, he was given the Kingdom of Sicily. To pay for his army, he borrowed money from Italian bankers. The Pope helped him by allowing him to use Church property as a guarantee. Five cardinals crowned him King of Sicily on January 5, 1266. Crusaders from France and Provence, a huge army, arrived in Rome ten days later.

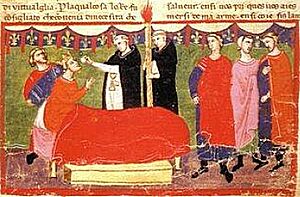

Charles decided to invade southern Italy right away. He couldn't afford a long war. He left Rome in January 1266. He marched towards Naples. But he changed his plan after hearing about Manfred's army near Capua. He led his troops across the mountains towards Benevento. Manfred also rushed to the town. Manfred attacked Charles's army on February 26, 1266. In the Battle of Benevento, Manfred's army was defeated, and he was killed.

Resistance across the kingdom collapsed. Towns surrendered even before Charles's troops reached them. The Muslim people of Lucera, a colony from Frederick II's time, swore loyalty to him. Charles's commander took control of the island of Sicily. Manfred's wife and children were captured. Charles claimed her dowry, which included the island of Corfu and a region in Albania. His troops seized Corfu by the end of the year.

Defeating Conradin

Charles was kind to Manfred's supporters at first. But they didn't believe it would last. They knew he had promised to return lands to nobles who had been exiled. Charles also couldn't win the loyalty of common people. He continued to collect an unpopular tax. He also banned foreign money in large deals. He made money by forcing people to exchange foreign money for local coins. He also traded in grain, spices, and sugar.

The Pope criticized Charles for his way of ruling. He called Charles arrogant. Charles's growing power in northern Italy also worried the Pope. To calm the Pope, Charles gave up his position in Rome in 1267. His successors demanded repayment of money Charles had borrowed.

The Pope asked Charles to send his troops to Tuscany. Charles's troops drove out his enemies from Florence in April 1267. Charles became the ruler of Florence and Lucca for seven years. He then hurried to Tuscany. Charles's expansion worried the Pope. The Pope summoned Charles and made him promise to give up all claims to Tuscany in three years. The Pope also convinced Charles to make agreements with the Prince of Achaea and the Latin Emperor. Charles's younger son, Philip, was named heir to Achaea. Charles also promised to help the Latin Emperor recapture Constantinople from the Byzantine emperor.

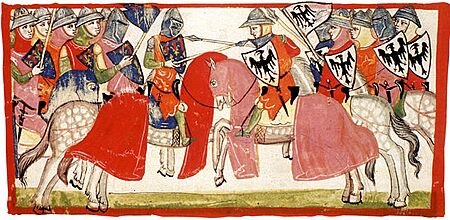

Charles returned to Tuscany and attacked a fortress. Meanwhile, Manfred's supporters had fled to Bavaria. They convinced Conradin, Manfred's 15-year-old nephew, to claim the Kingdom of Sicily. Conradin's supporters started a revolt in Sicily. The Muslims of Lucera also rebelled. The Pope urged Charles to return to Sicily. But Charles continued his campaign in Tuscany until March 1268. In April, the Pope made Charles his representative in Tuscany. Charles marched to southern Italy and attacked Lucera. But he then had to rush north to stop Conradin's invasion in August. At the Battle of Tagliacozzo on August 23, 1268, Conradin seemed to be winning. But a sudden attack by Charles's reserve army defeated Conradin.

People in many towns in southern Italy killed those who had supported Conradin. But the Sicilians and the Muslims of Lucera did not surrender. Charles marched to Rome. He was again elected as the head of Rome's government in September. He appointed new officials to collect taxes and administer justice. New coins with his name were made. For the next ten years, Rome was ruled by Charles's representatives.

Conradin was captured. Most of his followers were quickly executed. But Conradin and his friend were put on trial in Naples. They were sentenced to death and beheaded on October 29. Only one of Conradin's supporters was released. This happened after his wife threatened to execute the nobles she held captive. The nobles who supported the Emperor fled to the court of Peter III of Aragon. Peter had married Manfred's daughter.

Charles's Mediterranean Empire

Controlling Italy

Charles's first wife, Beatrice of Provence, died in 1267. Charles then married Margaret of Nevers in 1268. She was an heiress to her father's lands. The Pope died in 1268, and there was no new Pope for three years. This made Charles's power in Italy stronger. But it also meant he lacked the Church's support.

Charles returned to Lucera in April 1269 to lead the siege himself. The Muslims and other rebels resisted until they ran out of food in August 1269. Charles sent his son Philip to Sicily to force the rebels to surrender. They only captured one town. Charles sent a new commander to Sicily in August 1269. This commander captured more towns. Finally, the last rebel leader surrendered in early 1270.

Charles's troops forced Siena and Pisa, the last towns resisting him in Tuscany, to make peace in August 1270. He gave special rights to Tuscan merchants and bankers. This helped them in his kingdom. But his influence in northern Italy was decreasing. The towns there no longer feared an invasion after Conradin's death. Charles tried to strengthen his power there. But some towns only confirmed their alliance with him, not his rule.

The Eighth Crusade

Louis IX of France still wanted to free Jerusalem. But he decided to start his new crusade by attacking Tunis. Some say Louis believed the ruler of Tunis was ready to become Christian. Others say Charles convinced Louis to attack Tunis. Charles wanted to make sure Tunis paid the tribute it owed to the former Sicilian kings.

The French crusaders left in July 1270. Charles left Naples six days later. He spent over a month in Sicily waiting for his ships. By the time he landed in Tunis in August, many French soldiers had died from illness. Louis IX died the day Charles arrived.

The crusaders defeated the ruler of Tunis twice. This forced him to ask for peace. A peace treaty was signed in November. The ruler of Tunis agreed to pay Louis's son and Charles for the war costs. He also agreed to release Christian prisoners. He promised to pay Charles a yearly tribute. He also agreed to expel Charles's enemies from Tunis. The gold from Tunis, along with silver from a new mine, allowed Charles to make new coins.

Charles and Philip left Tunis in November. A storm scattered their ships. Most of Charles's ships were lost or damaged. Charles seized the damaged ships and their cargo. He ignored protests from Genoa. Before leaving Sicily, he gave temporary tax breaks to the Sicilians. He knew the conquest had caused much damage.

Attempts to Expand His Empire

Charles went with Philip III as far as Viterbo in March 1271. They failed to convince the church leaders to elect a new Pope. Charles's brother, Alphonse of Poitiers, became ill and died. Charles claimed most of Alphonse's inheritance. This included the Marquisate of Provence. Philip III disagreed, so Charles took the case to court in Paris. In 1284, the court ruled that these lands would return to the French crown if their rulers died without children.

An earthquake damaged the walls of Durazzo in Albania. Charles's troops took the town with help from local Albanian leaders. Charles made a deal with the Albanian chiefs in 1272. He promised to protect them and their old freedoms. He took the title of King of Albania. He also sent his fleet to Achaea to defend it from Byzantine attacks.

Charles hurried to Rome for the new Pope's enthronement in March 1272. The new Pope wanted to end conflicts between different Italian groups. While in Rome, Charles met with exiled leaders from Genoa. They offered him a leadership position. Charles promised them military help. In November 1272, Charles ordered his officials to arrest all Genoese people in his lands, except his allies. He also ordered their property to be seized. His fleet took control of Ajaccio in Corsica. The Pope criticized Charles's aggressive actions. But he suggested that Genoa elect Charles's allies as officials. Genoa ignored the Pope. They made alliances with other rulers against Charles in 1273.

The conflict with Genoa stopped Charles from invading the Byzantine Empire. But he continued to make alliances in the Balkans. The Bulgarian ruler was the first to make a treaty with him in 1272 or 1273. The rulers of Thessaly and Serbia also joined his alliance in 1273. However, the Pope forbade Charles to attack. The Pope hoped to unite the Orthodox and Catholic churches with the Byzantine Emperor's help.

A famous scholar, Thomas Aquinas, died unexpectedly near Naples in 1274. Some stories say Charles poisoned him. But historians say there is no proof of this. Churchmen from southern Italy accused Charles of being a tyrant at a council. This made the Pope try to make a deal with Rudolf of Habsburg, the new German king. In June, the Pope recognized Rudolf as the rightful ruler of Germany and Italy. Charles's sisters-in-law also claimed they had been unfairly treated in favor of Charles's late wife.

The Byzantine Emperor's envoy announced at the Council of Lyon in July that he accepted the Catholic faith. About three weeks later, the Pope again told Charles not to attack the Byzantine Empire. The Pope also tried to arrange a truce between Charles and the Emperor. But the Emperor chose to attack smaller states in the Balkans, including Charles's allies. The Byzantine fleet took control of the sea routes between Albania and Italy. The Pope only allowed Charles to send help to Achaea. The Pope's main goal was to organize a new crusade to the Holy Land. He convinced Charles to buy a claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem from a woman named Maria of Antioch.

The war with Genoa and other Italian towns took up more of Charles's time. He appointed his nephew as his deputy in Piedmont in 1274. But his nephew could not stop other towns from joining the anti-Charles alliance. The next summer, a Genoese fleet attacked Sicily. The Pope urged Charles to give up Tuscany. In the autumn of 1275, Charles's enemies offered peace. But he did not accept their terms. Early the next year, his enemies defeated his troops. This forced them to retreat to Provence.

Papal Elections and Influence

Pope Gregory X died in January 1276. Charles wanted to make sure a Pope who supported his plans was elected. Gregory's successor was Charles's ally. He quickly confirmed Charles as the head of Rome's government. He also helped make a peace treaty between Charles and Genoa in June 1276. Charles gave back privileges to Genoese merchants. He also gave up his conquests. Genoa recognized his rule in Ventimiglia.

This Pope died in June 1276. Charles's troops surrounded the building where the church leaders met. This allowed only his allies to communicate with others. In July, they elected Charles's old friend as Pope. But he died in August. The church leaders met again. Charles was nearby, but he couldn't directly influence the election. His strong opponent controlled the election. A new Pope was elected in September. He supported Charles's enemies in Piedmont. But he did not stop other Italian leaders from swearing loyalty to the German king. The Pope also confirmed a treaty. This treaty transferred claims to Jerusalem to Charles for money.

Charles appointed Roger of San Severino to rule the Kingdom of Jerusalem for him. San Severino arrived in Acre in June 1277. The town surrendered without a fight. At first, only some knights and Venetians recognized Charles as the ruler. But the nobles of the kingdom also swore loyalty to San Severino in January 1278. This happened after he threatened to take their lands. The Mamluks of Egypt had already limited the kingdom to a small coastal area. Charles had told San Severino to avoid conflicts with Egypt.

The Pope died in May 1277. Charles was ill and couldn't stop his opponent from being elected Pope in November. The new Pope soon declared that no foreign prince could rule in Rome. He reminded Charles that he had been elected for ten years. Charles swore loyalty to the new Pope in May 1278 after long talks. He had to promise to give up his positions in Rome and Tuscany in four months. On the other hand, the Pope supported Charles's enemies in Piedmont. He also started talks with the German king to stop him from making an alliance against Charles.

Charles announced he was giving up his positions in August 1278. He was replaced by the Pope's brother in Rome. The Pope's nephew replaced him in Tuscany. To make sure Charles gave up his ambitions in central Italy, the Pope started talks with the German king. They discussed restoring the Kingdom of Arles for Charles's grandson. Charles's sister-in-law strongly opposed this plan. But the King of France did not support his mother. After long talks, the German king recognized Charles as the ruler of Provence in 1279. An agreement about Charles's grandson ruling Arles was signed in 1280. This plan worried other rulers in the area.

Charles inherited the Principality of Achaea in 1278. He appointed an unpopular official from Sicily to rule Achaea. This official couldn't pay his troops. So they started robbing peasants. The Duke of Athens had to lend him money for salaries. Another ruler in Epirus recognized Charles's rule in 1279. He also gave three towns to Charles.

The Pope died in August 1280. Charles sent agents to promote one of his supporters for the next Pope. When a riot broke out, Charles's troops took control of the town. In February 1281, his strongest supporter was elected Pope. This Pope dismissed his predecessor's relatives. He made Charles the head of Rome's government again. Charles also sent an army to Piedmont. But it was defeated in May.

End of Church Unity

The Pope excommunicated the Byzantine Emperor in April 1281. This was because the Emperor had not forced church unity in his empire. The Pope soon allowed Charles to invade the empire. Charles's representative in Albania had already attacked a Byzantine fortress. A Byzantine army arrived in March 1281. Charles's representative was captured, his army fled, and Albania was lost to the Byzantines. In July 1281, Charles and his son-in-law made an alliance with Venice. They planned to restore the Roman Empire. They decided to start a full-scale campaign early the next year.

Charles's sister-in-law called a meeting of lords in the Kingdom of Arles in 1281. They wanted to stop Charles's army from taking the kingdom. But the King of France strongly opposed his mother's plan. The King of England would not promise any help. Charles agreed that his wife held some of her inherited lands as a Burgundian fief. This calmed the Duke of Burgundy. Charles's ships started gathering in Marseille in 1282. Another fleet was gathering in Sicily to start the crusade against the Byzantine Empire.

The Empire's Collapse

The Sicilian Vespers

Charles always needed money. He could not cancel a very unpopular tax in his kingdom. Instead, he gave tax breaks to some people and groups, especially French colonists. This made the burden heavier on those who didn't have such privileges. The forced exchange of local coins was also an important source of income. Charles also took forced loans when he needed large sums of money quickly.

Requisitioning goods also made Charles's government unpopular. His subjects were forced to guard prisoners or house soldiers. Restoring old fortresses and building new castles required many workers. But most of them didn't want to work on such long projects. Thousands of people were forced to serve in the army in foreign lands. Trading in salt became a royal monopoly. In December 1281, Charles again ordered the collection of the unpopular tax. He demanded 150 percent of the usual amount.

Charles did not pay much attention to the island of Sicily. He moved the capital from Palermo to Naples. He did not visit the island after 1271. This meant Sicilians could not tell him their problems directly. Sicilian nobles were rarely appointed as royal officials. But he often appointed nobles from southern Italy to represent him. Also, Charles had seized large estates on the island. He mostly used French churchmen to manage them.

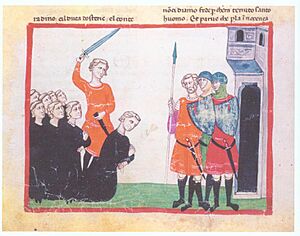

Stories say that a former official of Manfred of Sicily planned a plot against Charles. Legend says he visited Constantinople, Sicily, and Viterbo in disguise. He convinced the Byzantine Emperor, Sicilian nobles, and the Pope to support a revolt. The Byzantine Emperor later claimed he helped the Sicilians gain freedom. The Emperor sent money to the unhappy Sicilian nobles. Peter III of Aragon decided to claim the Kingdom of Sicily in 1280. He started gathering a fleet, pretending it was for another crusade to Tunis.

A riot broke out in Sicily in March 1282. A citizen of Palermo killed a French soldier who had insulted his wife. When the soldier's friends attacked the murderer, the crowd turned against them. They started killing all the French people in the town. This riot, known as the Sicilian Vespers, grew into a full uprising. Most of Charles's officials were killed or forced to flee. Charles ordered soldiers and ships to be sent to Sicily. But he could not stop the revolt from spreading. His commander in Acre also had to return to Italy.

The citizens of the major Sicilian towns formed their own governments. They sent delegates to the Pope, asking him to protect them. But the Pope instead punished the rebels in May. Charles issued an order in June. He accused his officials of ignoring his instructions for good rule. But he didn't promise big changes. In July, he sailed to Sicily and attacked Messina.

War with Aragon

Peter III of Aragon's envoy started talks with the rebel leaders in Palermo. They realized they couldn't resist without foreign help. So they accepted Peter and Constance as their king and queen. They sent envoys to meet Peter's fleet. After some thought, Peter decided to help the rebels. He sailed to Sicily. He was declared king of Sicily in Palermo in September. After this, two kingdoms existed for over a century. Charles and his successors ruled southern Italy (the Kingdom of Naples). Peter and his descendants ruled the island of Sicily.

Charles had to retreat from the island when the Aragonese landed. But the Aragonese quickly destroyed part of his army and most of his supplies. Peter took control of the whole island. He sent troops to southern Italy. But they couldn't stop Charles's son from bringing 600 French knights to join his father. More French troops arrived in November. In the same month, the Pope punished Peter.

Neither Peter nor Charles could afford a long war. Charles made a surprising offer in December 1282. He challenged Peter to a duel. Peter wanted to continue the war. But he agreed that a battle between the two kings, each with 100 knights, should decide who owned Sicily. The duel was set for June 1283 in Bordeaux. Charles appointed his son to rule his kingdom while he was away. To keep the loyalty of local lords in Achaea, he appointed one of them to rule. The Pope declared the war against the Sicilians a crusade in January 1283. Charles met with the Pope in March. But he ignored the Pope's ban on his duel with Peter. After visiting France, he left for Bordeaux. The duel became a joke. Both kings arrived at different times, declared victory, and left.

Small fights continued in southern Italy. Aragonese fighters attacked a town and killed Charles's nephew in January 1283. The Aragonese seized another town in February. The Sicilian admiral defeated a new French fleet in April. However, tensions grew between the Aragonese and the Sicilians. In May 1283, one of the rebel leaders was executed for secretly talking with Charles's agents. The Pope declared the war against Aragon a crusade. He gave the kingdom to the French king's son in February 1284.

Charles started raising new troops and a fleet in Provence. He told his son to stay on the defensive until he returned. The Sicilian admiral blocked Naples in May 1284. Charles's son tried to destroy the squadron. But most of his fleet was captured. He himself was taken prisoner after a short fight in June. News of this defeat caused a riot in Naples. But a papal representative stopped it with the help of local nobles. Charles learned of the disaster when he landed in Italy in June. He was very angry at his son for disobeying him. He supposedly said, "Who loses a fool loses nothing," referring to his son's capture.

Charles left Naples for Calabria in June 1284. A large army went with him. He attacked the town by sea and land in July. His fleet approached Sicily, but his troops could not land. After the Sicilian admiral landed troops nearby, Charles had to stop the attack and retreat from Calabria in August.

Death of a King

Charles went to Brindisi and prepared for a campaign against Sicily in the new year. He sent orders to his officials to collect the unpopular tax. However, he became very ill before traveling to Foggia in December. He made his last will in January 1285. He appointed his nephew to rule for his grandson. His grandson would rule until Charles's son was released. Charles died on the morning of January 7. He was buried in Naples. His heart was placed in a church in Paris. His body was moved to a chapel in the new Naples Cathedral in 1296.

Family

| Louis VIII of France | Blanche of Castile | Ramon Berenguer IV of Provence | Beatrice of Savoy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert I of Artois | Alphonse of Poitiers | Charles I of Anjou | Beatrice of Provence | Eleanor of Provence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis IX of France | Margaret of Provence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert II of Artois | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philip III of France | Peter I of Alençon | Edward I of England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Records show that Charles was a loyal husband and a caring father. His first wife, Beatrice of Provence, had at least six children. Some stories say she convinced Charles to claim the Kingdom of Sicily. She wanted to wear a crown like her sisters. Before she died in 1267, she left the use of Provence to Charles.

- Blanche, Charles and Beatrice's oldest daughter, married Robert of Béthune in 1265. She died four years later.

- Beatrice, her younger sister, married Philip, the Latin Emperor, in 1273.

- Charles II, Charles's oldest son, was given the Principality of Salerno in 1272. Charles II and his wife, Maria of Hungary, had fourteen children. This ensured the family line continued.

- Philip, Charles and Beatrice's next son, was elected king of Sardinia in 1269. But this was without the Pope's permission. He died without children in 1278.

- Robert, Charles's third son, died in 1265.

- Elisabeth, Charles's youngest daughter, married the future Ladislaus IV of Hungary in 1269.

Charles's first wife died. He then wanted to marry Margaret of Hungary. But Margaret, who grew up in a convent, did not want to marry. Charles and his second wife, Margaret of Nevers, had several children. But none of them lived to adulthood.

Charles's Legacy

Historians have different views about Charles. Some described him as a tyrant. Others praised him. Charles continued some policies of earlier rulers, like taxes. But his rule also brought French and Provençal influences to his kingdom. He gave land in his kingdom to about 700 nobles from France or Provence. He dressed like other Western European kings, not in the rich styles of earlier Sicilian kings.

Around 1310, a historian said Charles was the most powerful Christian king in the late 1270s. A poet even compared Charles to Charlemagne. This shows that Charles was seen as almost an emperor. Modern historians also agree that Charles tried to build a large empire.

One historian concluded that Charles's lands were "too large to control." However, economic ties between his lands grew stronger. Salt from Provence was sent to his other lands. Grain from his kingdom was sold in other areas. Merchants from Tuscany settled in his lands. His top officials were moved between his different territories. Even though his empire fell apart before he died, his son kept southern Italy and Provence.

Charles always stressed his royal rank. But he did not use "imperial" language. One of his legal experts developed a new legal theory. He argued that a king could make laws, just like an emperor. To encourage legal studies, Charles paid high salaries to law teachers at the University of Naples. Medical teachers also received good pay. The university became a major center for medical science. Charles was personally interested in medicine. He borrowed Arabic medical texts from the rulers of Tunis to have them translated. He hired a Jewish scholar who could translate texts from Arabic to Latin.

Charles was also a poet, which was unusual for his family. He wrote love songs and other poems. He was asked to judge two poetry competitions when he was young. But modern scholars don't think his poetry was very good. Poets from Provence often criticized Charles. But French poets praised him. One poet wrote a poem against the salt tax. Another criticized Charles for invading Sicily. A French poet dedicated an unfinished epic poem to Charles. Another glorified his victories. A famous Italian poet described Charles singing peacefully with his rival in Purgatory.

Charles was also interested in architecture. He designed a tower in Brindisi, but it collapsed. He ordered the building of the Castel Nuovo in Naples. Only the chapel from his time remains. He is also credited with bringing French-style stained glass windows to southern Italy.

See also

In Spanish: Carlos de Anjou para niños

In Spanish: Carlos de Anjou para niños