Chinese ritual bronzes facts for kids

Ancient Chinese bronzes are amazing metal objects made a very long time ago. Starting around 1650 BC, people in China began placing beautifully decorated bronze containers in the tombs of kings and important people. These bronzes were special items, not for everyday use. They were used in ceremonies to offer food and drinks to ancestors and gods. These ceremonies often happened in family temples or special halls built over tombs. It was like a big family dinner where both living and dead family members were thought to join in.

When someone important who owned a bronze vessel died, the vessel was often buried with them. This was so they could continue their ceremonies in the afterlife. Many of the bronze pieces we find today were dug up from these ancient tombs. Besides containers for food and drink, people also made weapons and other items out of bronze for these special rituals. Another very valuable material used for ritual objects was jade, which had been used for tools and weapons since about 4500 BC.

At first, the ruler probably controlled who could make bronze. Giving bronze metal to noble families was a sign of the ruler's favor. The way bronze was made was written down in an old book called the Kao Gong Ji, which was put together between 500 and 300 BC.

Contents

Why Were Chinese Bronzes Used?

Chinese bronzes (called 青铜器; 青銅器; qīng tóng qì; ch'ing t'ong ch'i) are some of the most important pieces of ancient Chinese art. They even have their own special section in old Imperial art collections. The Chinese Bronze Age started during the Xia dynasty (around 2070-1600 BC). The making of bronze ritual containers became very popular during the Shang dynasty (around 1600-1046 BC) and the early part of the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BC).

Most of the ancient Chinese bronze items we still have today were made for rituals, not for everyday use like tools or weapons. Even weapons like daggers and axes had a special meaning. They showed the ruler's power from the heavens. Because these bronze objects were so important in religion, many different types and shapes of vessels were created. These shapes became classic and were copied later in other materials, like Chinese porcelain.

Old Chinese ritual books explained exactly who was allowed to use which kinds of special vessels and how many. For example, the king of Zhou could use 9 dings and 8 gui vessels. A duke was allowed 7 dings and 6 guis. A baron could use 5 dings and 3 guis, and a nobleman could use 3 dings and 2 guis.

Archaeologists found the tomb of Fu Hao, a very powerful Shang queen. Her tomb contained over two hundred ritual vessels, which was many more than the twenty-four vessels found in a nobleman's tomb from the same time. This showed her high status to everyone, including, they believed, her ancestors and spirits. Many pieces even had her special name carved into them, showing they were made just for her burial.

How Were Bronzes Made?

Piece-Mould Casting

From the Bronze Age all the way to the Han Dynasty, the main way ancient China made ritual vessels, weapons, and other items was called piece-mould casting.

Here's how it worked:

- First, a clay mould was made around a model of the object. This mould was then cut into sections.

- Another way was to make a mould inside a clay-lined box and press a design into it.

- Next, these mould pieces were baked.

- Then, they were put back together. Clay was poured in to make a casting, and parts were removed.

- This clay casting looked like the final product. It was dried and then flattened to create a core. This core set the space for the metal, deciding how thick the finished bronze would be.

- The mould pieces were then put back around the core.

- Finally, melted bronze was poured into the space. After the metal cooled, the clay moulds were broken, and the bronze object was taken out. It was then polished to make it shiny. The number of pieces the mould was cut into depended on the object's shape and design.

Casting-On Technique

Casting-on is an old Chinese method used to attach handles and other small parts to bigger bronze objects. This technique was used early in the Bronze Age. It was important for making things like bronze chains for ornaments.

Lost-Wax Casting

The earliest signs of lost wax casting in China were found around 600 BC. This was at a cemetery in Xichuan, Henan province. Some bronze objects were first made using the piece-mould method. Then, fancy handles with open designs were added using the lost-wax process. These handles were made separately and then attached.

Lost-wax casting came to China from the ancient Near East. We don't know exactly when or how it arrived. This method is better for making decorations with deep cuts and openwork designs. It's harder to do these with piece-moulds. Even though lost-wax casting wasn't used for very large vessels, it became more popular later, between the late Eastern Zhou and Han dynasties. It was also cheaper for making small parts because it was easier to control the amount of metal used.

Here's how lost-wax casting works:

- First, you make a model of the object, usually out of wax. Wax is easy to shape and melts away when heated.

- Then, the wax model is covered with clay to make a mould. The first layer of clay is brushed on carefully to avoid air bubbles.

- Next, the clay is baked. The wax inside melts and drains out (this is why it's called "lost wax").

- Melted metal is then poured into the empty clay mould.

- After the metal cools, the baked clay mould is broken open. This reveals the finished metal object, which is an exact copy of the original wax model.

Types of Chinese Bronze Vessels

People started collecting and appreciating Chinese bronzes as art (not just ritual items) during the Song dynasty. This became very popular during the Qing dynasty, especially under the Qianlong Emperor. His huge collection is listed in special books called the Xiqing gujian and the Xiqing jijian.

In these books, bronze items are sorted by what they were used for:

- Sacrificial vessels (for offerings)

- Wine vessels

- Food vessels

- Water vessels

- Musical instruments

- Weapons

- Measuring containers

- Ancient money

- Miscellaneous (other items)

The most valuable bronzes are usually the sacrificial and wine vessels. Many of these are decorated with special taotie designs.

Sacrificial Vessels

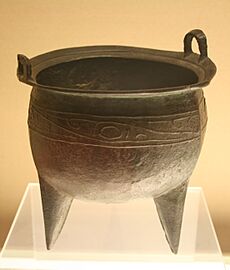

- Dǐng (鼎): A sacrificial vessel, originally a pot for cooking and storing meat. Early ones were round bowls, wider than tall, with three legs and two short handles. Later dings became very large and showed power. They are considered the most important type of Chinese bronze culturally. There's also a square version called a fāngdǐng (方鼎) with four legs.

- Dòu (豆): A sacrificial vessel that was originally for food. It's a flat, covered bowl on a long stem.

- Zūn (尊): A tall, cylindrical wine cup used for sacrifices. It has no handles or legs. The top is usually a bit wider than the body. Later, these vessels became very fancy, often shaped like animals.

Wine Vessels

- Gōng (觥): A wine vessel often long and shaped like an animal. It always has a cover.

- Gū (觚): A tall wine cup with no handles. Its mouth is wider than its base.

- Guǐ (簋): A bowl with two handles.

- Hé (盉): A wine vessel shaped like a teapot with three legs. It has a handle and a spout pointing diagonally upwards.

- Jiǎ (斝): A pot for warming wine. It's like a dǐng but taller and might have two sticks pointing up from the rim as handles.

- Jué (爵): A wine cup with three legs, a spout, a pointed extension on the opposite side, and a handle.

- Lì (鬲): A cauldron with three legs. Similar to a dǐng, but its legs blend into the body or have large swellings.

Food Vessels

- Duì (敦): A round dish with a cover to keep its contents clean.

- Pán (盤): A round, curved dish for food. It might have no legs, or three or four short ones.

- Yǒu (卣): A covered pot with a single looping handle attached on opposite sides of the mouth.

Water Vessels

- Dǒu (斗): A scoop. It's a tall bowl with a long handle.

- Píng (瓶): A tall vase with a long, thin neck and a narrow opening.

- Wèng (瓮): A round jar with a round mouth and belly, used for holding water or wine.

- Yí (匜): A bowl or pitcher with a spout. It can be shaped like an animal.

- Yú (盂): A basin for water. It might have up to four decorative handles around the edge.

Musical Instruments

- Gǔ (鼓): A drum.

- Líng (鈴): A small bell.

- Zhōng (鐘): A large bell, like one that might hang in a tower.

Weapons

- Jiàn (劍): A sword.

- Nǔjī (弩機): A crossbow mechanism.

- Zú (鏃): An arrow head.

Measuring Containers

- Zhī (卮): A wine vessel that was also used for measuring. It's like a píng but shorter and wider.

Ancient Money

- Qián (錢): Ancient money. It came in different shapes, including cloth-shaped, knife-shaped, and round coins.

- Yuán (圓): Also called yuánbì or yuánqián. These were circular coins with a hole in the middle, usually made of copper or bronze. This is what most people think of as 'Chinese money'.

Miscellaneous Items

- Jiàn (鑑): This can mean two different things: a tall, wide bronze dish for water, or a round bronze mirror with fancy designs on the back. Today, it mostly means a mirror.

- Shūzhèn (書鎮): A paperweight. These were usually solid bronze, shaped like a resting animal.

Patterns and Decorations on Bronzes

The Taotie Design

The taotie pattern was a very popular design on bronze items during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Scholars from the Song dynasty (960–1279) named it after a monster mentioned in an old book. This monster had a head but no body.

The earliest taotie designs on bronzes, from the early Erligang period, were simple. They showed a pair of eyes with some lines stretching out to the sides. Soon, the design became more detailed, showing a full face with oval eyes and a mouth. This face then continued into the side view of a body on each side. The taotie became a fully developed monster mask around the time of King Wu Ding, in the late Shang period.

A typical taotie pattern looks like a full-face animal mask with round eyes, sharp teeth, and horns. However, people sometimes argue about what it was really meant to be. In all these patterns, the eyes are always the most important part. Their huge eyes make a strong impression, even from far away.

Each taotie pattern is unique because, in the early days of casting, one ceramic mould could only make one bronze object. The patterns are usually the same on both sides (symmetrical) around a middle line. The lower jaw area is usually missing. The biggest difference between taotie patterns is the "horns." Some look like ox horns, some like sheep horns, and some have tiger's ears.

How Bronze Styles Changed Over Time

Starting in the 1930s, an art historian named Max Loehr studied how decorative styles on pre-Zhou bronze vessels changed. He found five different styles. Even though the vessels he studied didn't have clear origins, he thought they came from the Late Shang site of Yinxu. Later, when archaeologists found vessels with clear origins, his ideas were proven right. However, the timeline was longer than he first thought, starting in the Erlitou period and reaching his Style V early in the Late Shang period.

- Style I: Vessels had thin, raised lines carved into the mould. This meant the design was naturally divided into sections. The main design was the taotie. This style is found on the earliest decorated bronzes from Erlitou and some from the next period, Erligang.

- Style II: The raised lines became thicker in some places. Another design, a one-eyed animal seen from the side (often a dragon), was also used. This style is common in the Erligang period.

- Style III: Designs became more complex and covered more of the vessel's surface. Many new designs and types of raised patterns were added. The designs were now carved directly onto the model. It was during this time that bronze-making techniques spread widely, and new styles appeared in the Yangtze valley.

- Style IV: This style changed how designs were made clear. Motifs were shown with fewer lines, which stood out against a background of many thin lines. These background areas were filled with fine spirals called léiwén (雷文). The main designs became clearer, and images of birds and animals from nature joined the taotie and dragon.

- Style V: This style built on Style IV. The main designs were raised even higher, making them stand out more from the background. Raised edges were used to divide the design into sections. Many bronze vessels found in the tomb of Fu Hao, a queen from the Late Shang period, are decorated in Style V.

- Examples of how decorative styles changed over time

- Vessels from Hunan, 13th–11th centuries BC

Western Zhou Styles

Bronze vessels from the Western Zhou period can be divided into early, middle, and late periods based on their shape, decoration, and the types of vessels that were popular. The most common vessels throughout this time were the guǐ basin and the dǐng cauldron. These were also the vessels most likely to have long writings carved on them.

- Early Western Zhou: Vessels were fancy versions of Late Shang designs. They had high-relief decorations, often with noticeable flanges (raised edges), and used a lot of the taotie design. Wine vessels like Jué, jiǎ, and gū were still made, but they mostly disappeared later. Yǒu and zūn were usually made in matching sets. The earliest guǐ vessels were raised on a base. Over time, vessels became less flashy.

- Middle Western Zhou: By the mid-10th century BC, the taotie design was replaced by pairs of long-tailed birds facing each other. Vessels became smaller, and their shapes were simpler. New types of vessels appeared, like the hú vase, zhōng bell, and xǔ vessel. Guǐ vessels from this time usually had covers.

- Late Western Zhou: New types of vessels started to appear in the early 9th century BC. These new types were often found in large sets, possibly because Zhou ritual practices changed. Animal decorations were replaced by geometric shapes like ribs and diamond patterns. On the other hand, legs and handles became larger and more detailed, often topped with animal heads.

- Western Zhou {{py|guǐ}} vessels

- Western Zhou {{py|dǐng}} cauldrons

Spring and Autumn Period Styles

For the first 100 years of the Spring and Autumn period, designs mostly followed those of the late Western Zhou. Over time, vessels became wider and shorter, and dragon decorations started to appear. Around the middle of this period, several new ways of making bronzes were adopted. These helped create new designs with more complex shapes. For example, the body and attachments of a vessel could be cast separately and then welded together. Also, using reusable pattern blocks made production faster and cheaper.

See Also

- Chinese bronze inscriptions

- History of Chinese archaeology