Coandă-1910 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coandă-1910 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

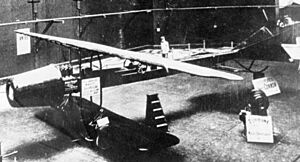

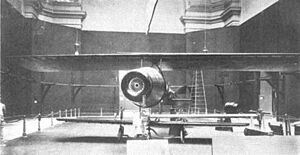

| Coandă-1910 at the 1910 Paris Flight Salon | |

| Role | Experimental |

| National origin | Romania/France |

| Manufacturer | Henri Coandă |

| Number built | 1 |

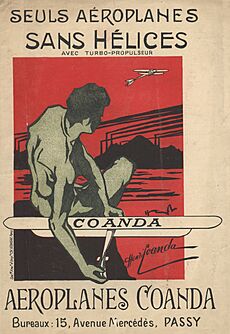

The Coandă-1910 was a very unusual airplane designed by a Romanian inventor named Henri Coandă. It was a type of aircraft called a sesquiplane, which means it had two main wings, but one was much smaller than the other. What made it really special was its engine. Instead of a normal propeller, it used something Coandă called a "turbo-propulseur." This engine had a regular piston engine that powered a big fan, which pushed air out the back.

This strange airplane got a lot of attention at an air show in Paris in October 1910. It was the only plane there without a propeller! But after the show, the Coandă-1910 wasn't seen much, and people forgot about it. Coandă later used a similar engine for a snow sledge, but he didn't use it for airplanes again for a long time.

Many years later, after real motorjets and turbojets were invented, Coandă started telling different stories. He claimed his old engine was the first "jet" engine, even saying it burned fuel in the air stream. He also said he made a short flight in December 1910, crashing and destroying the plane in a fire. But some aviation historians disagreed. They said there was no proof his engine burned fuel in the air, and no proof the plane ever flew. In 1965, Coandă showed some drawings to support his claims, but these drawings looked changed from the originals. Many historians believed Coandă's engine just pushed "plain air," not a powerful jet from burning fuel.

Still, in 2010, Romania celebrated the 100th anniversary of the jet aircraft, believing Coandă invented the first one. They even made a special coin and stamp! A working copy of the Coandă-1910 was also started. An exhibition at the European Parliament honored the building and testing of this unique plane.

Contents

How the Idea Started

Coandă was interested in flying with rockets as early as 1905. He did tests with model airplanes that had rockets attached in Romania. In secret, he also tested a flying machine in Germany. This machine had a propeller at the front and two other propellers that spun in opposite directions to help it lift. It was powered by a 50-horsepower engine. Coandă claimed he tested this plane in Germany, and even the German leader saw it. Around this time, Coandă became interested in jet propulsion. He said he showed this plane and a jet-powered model in Berlin in 1907.

Coandă continued his studies in Belgium. With his friend Giovanni Battista Caproni, he built a glider based on designs by other famous glider pioneers. In 1909, he worked as a technical director for an aeroclub. Later that year, he built another glider with help from a car maker.

The 1910 Airplane

Coandă moved to Paris in 1909 to continue his experiments. He wanted to test airplane wings at faster speeds. He got help from important people like Ernest Archdeacon and Gustav Eiffel. With their support, he could test different wing shapes using a platform on the front of a train! He also started flying lessons in a Hanriot monoplane.

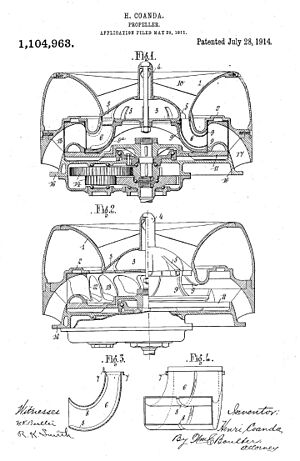

With a school friend, Coandă began building his special sesquiplane and its unusual engine. He tested the engine's power in his workshop. He also applied for several patents for his engine and airplane in May 1910.

Coandă showed his airplane at the Second International Aeronautical Exhibition in Paris, from October 15 to November 2, 1910. His plane, along with the first floatplane, was placed in a special upstairs area. It was separate from the more common airplanes on the main floor.

The Coandă-1910 was built in a very new way for its time. It was a sesquiplane, which made it harder to build but helped with stability. Its wings were strong and didn't need extra wires to hold them up. Coandă said the wings had metal parts, but photos show they were mostly wood inside. The back edges of the top wing could twist for control or braking. The body of the plane was triangular and covered with shaped plywood. It had special cooling pipes for the engine near the cockpit. The tail was shaped like a cross. Four triangular parts at the back of the tail were controlled by two large steering wheels. These parts helped the plane go up and down and turn. This was an early version of what we now call a V-tail.

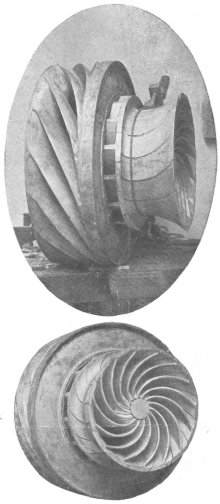

The most amazing part of the plane was its engine. Instead of a propeller, a 50-horsepower engine drove a spinning fan through a gearbox. This fan pulled air in from the front and pushed it out the back. The fan was inside a cover at the front of the plane. Coandă later claimed this engine could create a lot of thrust. People at the time called it different names, like a "turbine without propellers" or a "ducted fan."

Some reporters doubted the engine could make enough thrust. They noted the engine was small for the plane's size. They wondered if the air intake was too small to produce the claimed power.

The Coandă-1910 was supposedly sold to Charles Weymann in October 1910. A newspaper said it would fly near Paris soon, piloted by Weymann. Another paper said it was "sold twice-over." Maybe Weymann wanted to buy it after it was tested.

People at the exhibition had mixed feelings. Some thought the plane would never fly. Others found it very original and clever. A reporter wrote that it was too early to say if it would replace propellers, but the idea was "interesting." The official report focused on the wings and tail, not the engine. One magazine wrote that if the machine worked as Coandă hoped, it would be "a beautiful dream."

After the exhibition, the plane was moved for more testing. Modern Romanian researchers looked at old photos. They thought the engine shown at the exhibition was not fully finished. They believed the exhaust gases from the engine were not sent to the fan as described in the patent. A historian named Gérard Hartmann said the engine only made a small amount of thrust. To take off, it would have needed much more. He said the fan would have had to spin so fast it might explode. This was not tried. But Hartmann concluded that the experiment showed the idea could work.

In 1912, a magazine writer recalled the Coandă-1910 as the "chief attraction" of the 1910 show. He said Coandă told him the plane reached a speed of 112 kilometers per hour (70 mph) during "flight tests." The writer doubted this claim, and no proof ever appeared.

Other Projects

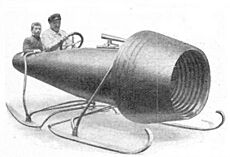

Coandă used his engine design for a motorized snow sled. This sled was built for a Russian Grand Duke. It had a 30-horsepower engine driving the turbo-propulseur. The sled was shown at an automobile show in Paris in December 1910. Magazines published photos of it. One magazine expected it to go 60 mph, but there are no records of it being tested.

Coandă kept working on the Coandă-1910 in 1911. He wanted to make it more stable and powerful. He applied for new patents for improvements. He thought about using two engines to power the fan. These engines were air-cooled, which meant he probably didn't plan to inject fuel into the jet stream and ignite it. He also thought about adding landing gear that could fold up into the plane.

The 1910 project was very expensive for Coandă. He spent about one million francs, which left him with little money. He then built the Coandă-1911 to try and win a French Army aviation competition. This competition required planes to have two engines for safety. Coandă showed a model of this new plane. It used two engines connected to one propeller. But it didn't provide enough power. The plane flew in October 1911, but not very well. It was too heavy, and the engine changes didn't help enough.

After this, Coandă moved to the United Kingdom to work for an airplane company. For the next 40 years, he worked on many different inventions. During World War II, he brought back his turbo-propulseur engine idea. The German Army hired him to develop an air propulsion system for military ambulance snow sleds, similar to the one he made for the Russian Grand Duke. This project ended after a year without any production plans. Coandă had experimented with different nozzles, but he never tried to inject fuel and burn it in the air stream like a true jet engine.

The Coandă-1910 and its engine were not mentioned in many aviation books of that time. Even a big encyclopedia about jet and rocket engines from the 1920s and 30s didn't mention Coandă.

Later Claims and Disagreements

When real jet engines arrived, people started writing histories of the technology. A 1946 study described the Coandă-1910 as "probably not flown." But it noted it had a "mechanical jet propulsion device with a centrifugal blower." It also said heat from the piston engine "furnished auxiliary jet propulsion." A magazine called Flight said it was "scarcely a jet."

In 1950, a book claimed Coandă flew the first jet plane for 30 meters (100 ft) and then crashed. In 1953, Flight magazine mentioned the Coandă-1910 "ducted fan." It quoted Coandă saying he "took off for a few feet, then came down hurriedly and broke two teeth."

In the early 1950s, Coandă began to claim he flew his 1910 plane himself. He said the 1910 engine was the first motorjet, using fuel injection and burning fuel to create thrust. In 1955 and 1956, many articles presented Coandă's version of events. He said he took off and crashed in December 1910, with other famous aircraft makers watching. Coandă himself spoke about it, saying he "intended to inject fuel into the air stream," implying he never finished that part. A writer named Martin Caidin wrote "The Coanda Story" based on an interview. Another writer, René Aubrey, wrote a different story, saying Coandă flew on December 16, 1910, that fuel was definitely injected, and it was "the first jet flight in the world." Aubrey said the plane stalled, Coandă was thrown clear, and the plane "gently collapsed to the ground" and burned.

In 1956, Coandă published an article called "The First Jet Flight." He wrote:

"In December, we brought the airplane out of its hangar... I climbed into the cockpit, accelerated the motor, and felt the power from the jet thrust straining the plane forward... I had anticipated that I would not attempt to fly today, but would make only ground tests... The controls seemed too loose to me, so I injected fuel into the turbine. Too much! In a moment I was surrounded by flames! ... I saw that the plane had gained speed, and that the walls of the ancient fortifications bordering the field were lunging toward me. I pulled back on the stick, only much too hard. In a moment the plane was airborne, lunging upward at a steep angle. I was flying—I felt the plane tipping—then slipping down on one wing. Instinctively, I cut the gas... The next thing I knew, I found myself thrown free of the plane, which slowly came down, and burst into flames... I had flown the first jet airplane."

A friend of Coandă's, Major Victor Houart, wrote in 1957 that he saw Coandă fly and crash. He said Coandă taxied twice, lifted off to avoid a wall, caused flames by adding too much power, and was thrown from the plane when it hit the wall. Houart said Coandă was "not badly hurt." Coandă also claimed his 1910 plane had movable wing parts, retractable landing gear, and a fuel tank in the top wing. In 1965, Coandă gave drawings and photos of the plane to the National Air and Space Museum (NASM).

A rocket engineer named G. Harry Stine worked with Coandă. In 1967, Stine wrote that Coandă flew on December 10, 1910. He described the heat from the "two jet exhausts" as being "too much." After Coandă's death, Stine wrote more about the plane. He said Coandă's engine had "elements of a true jet," but the patent didn't mention injecting fuel into the compressed air. He believed the first *pure* jet flight was in Germany in 1938.

In 1965, a NASM historian interviewed Coandă. Coandă said the December 1910 flight was not an accident. He wanted to test five things: the plane's structure, engine, wing lift, controls, and aerodynamics. He said the engine's heat was "fantastic," but he used special plates to direct the jet blast away. He claimed that as the plane moved and lifted, the "exhaust flame... curved inward and ignited the aircraft." Coandă said he brought the plane down under control, but the landing was "abrupt," and he was thrown clear. The plane then burned completely.

Why Some Disagreed

In 1960, Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith, an aviation historian, responded to the claims that Coandă built and flew the first jet. Gibbs-Smith wrote that the Coandă-1910 was a wooden sesquiplane with a 50-horsepower engine driving a "ducted air fan." He said this fan pushed "plain air" to move the plane. He noted that "no claims that it flew, or was even tested, were made at the time." He said the story of it flying only appeared in the 1950s.

Gibbs-Smith pointed out that the airfield where the test supposedly happened was always watched by the French Army, reporters, and experts. He said any exciting event like a crash and fire would have been in newspapers and military reports. But there were no records of the Coandă-1910 being tested, flown, or destroyed. Gibbs-Smith also said the plane did not have retractable landing gear, special wing slots, a fuel tank in the wing, or fuel injected into any turbine. He also said a pilot would have been killed by the heat if any burning had happened in the engine's air stream.

In 2010, Dan Antoniu, a Romanian expert, wrote that Gibbs-Smith guessed the plane was never tested because he couldn't find proof. But Antoniu also couldn't find concrete proof of a test flight. Antoniu also said Gibbs-Smith didn't check Coandă's French patents from 1910 and 1911, which described some of the features Gibbs-Smith said didn't exist.

In 1980, NASM historian Frank H. Winter looked at the drawings Coandă gave in 1965. Winter wrote that these drawings had new details about the engine's inside that weren't in any earlier accounts or patents. He said Coandă told different stories about his claimed 1910 flight. Winter noted that the drawings Coandă provided were clearly made in the 1960s, not 1910. He also said the fuel injection parts looked like they were added even later to the original drawings. So, the drawings themselves didn't prove Coandă's claims.

Winter wondered why Coandă didn't add the new feature of fuel injection and burning to his 1911 patent if it was there during his supposed flight. He found that the early patents were for air *or water* flowing through the device, meaning they couldn't include fuel combustion. He also noted that early patents didn't mention heat shields or fuel injection.

Winter also checked old newspapers and aviation magazines from December 1910. He found that there was bad weather at the airfield during the time Coandă claimed his flight happened. No flying took place then. Other aircraft tests were listed, but no mention of Coandă or his plane.

Winter also found that an Italian engineer, Camille Canovetti, had been working on a similar engine before Coandă. Canovetti had patented his machine in 1909 and 1910. Canovetti wrote in 1911 that Coandă's engine "called general attention" to designs like his.

What People Say Now

Today, books about aviation history have different views on the Coandă-1910. Some recognize Coandă for discovering the Coandă effect (how fluids stick to curved surfaces). But they usually give Hans von Ohain credit for designing the first jet engine to power a manned flight, and Frank Whittle for completing and patenting the first jet engine for flight. Some authors, like Joe Christy and LeRoy Cook, still say Coandă's 1910 plane was the first jet.

Aviation author Bill Gunston changed his mind about Coandă. In 1993, he gave Coandă credit for the first jet engine. But in 1995, he wrote that Coandă's plane "inadvertently became airborne, crashed and burned." He called it "of no more significance" than other early jet attempts. In later books, Gunston didn't include Coandă at all.

Walter J. Boyne, a former director of the NASM, mentions Coandă a few times. He wrote that Coandă's 1910 jet aircraft "was superbly built and technically advanced—and could not fly." He also said: "Countless loyal Coanda fans insist that the airplane flew. Others say it merely crashed."

In 1980 and 1993, Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation called the Coandă-1910 the "world's first jet-propelled aircraft to fly." But in 2003, Frank Winter and F. Robert van der Linden wrote that it was an unsuccessful ducted fan aircraft with no proof of a flight test.

Tim Brady, an aviation dean, wrote in 2000 that the jet's story is about three men: Henri Coandă, Sir Frank Whittle, and Pabst von Ohain. He agreed that Coandă's plane flew "for about a thousand feet [300 m] before crashing into a wall." In 1990, a paper said Coandă was a "pioneer of jet flight" and built the "first jet aircraft, the 'Coanda-1910'." But in 2007, Ron Miller wrote that Coandă's engine was an "earliest attempt" but was "incapable of actual flight." The question of whether the Coandă-1910 was the first jet aircraft is still debated.

In the 2000s, Dan Antoniu and other Romanian aviation experts studied photos of the Coandă-1910. They believe the plane shown at the exhibition was not finished. Antoniu wrote that the engine's exhaust pipes were open, with no way to send gases to the fan as patented. Also, there were no heat shields for the crew. He also thought the way the wings were attached to the body seemed unsafe. The tail design also seemed to make it hard to control.

Remembering the Plane

A full-size copy of the Coandă-1910, built in 2001, is on display in Bucharest at the National Military Museum. A smaller model is at the French Air and Space Museum near Paris. At the old airfield where the plane was tested, a plaque lists famous flight pioneers. Later, another plaque honoring Coandă and another Romanian engineer was placed nearby.

Building a full-size working copy of the plane started in March 2010 in Romania. This copy is based on plans Coandă redrew in 1965 because the original 1910 plans were lost. It uses metal instead of wood for the body. Its engine will be a real jet engine from a 1960s military trainer plane.

In October 2010, the National Bank of Romania made a special silver coin to celebrate 100 years since the first jet aircraft was built. The coin shows the plane on one side and Coandă's face on the other. In the same month, the Romanian Post made a special stamp. It shows a modern drawing of the Coandă-1910's engine and a quote from Gustave Eiffel: "This boy was born 30 if not 50 years too early." In December, the president of the European Parliament opened an exhibition celebrating the Coandă-1910.

Specifications

Data from Contemporary pamphlet

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 12.5 m (41 ft 0 in)

- Wingspan: 10.3 m (33 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 32 m2 (340 sq ft)

- Gross weight: 420 kg (926 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Four-cylinder, inline, water-cooled engine driving a compressor , 37 kW (50 hp)

Related

- Stipa-Caproni

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |