Confederate Conscription Acts 1862–1864 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Confederate Conscription Acts 1862–1864 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Acts to further provide for the public defence | |

| Territorial extent | Confederate States |

| Enacted by | Confederate States Congress |

| Date enacted | Second Conscription Act September 27, 1862 |

| Introduced by | Jefferson Davis |

| Status: Repealed | |

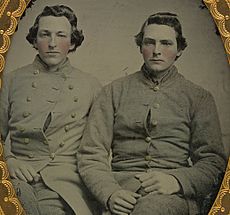

The Confederate Conscription Acts were special laws passed by the Confederate government during the American Civil War. These laws were put in place between 1862 and 1864 to get enough soldiers to fight the war.

The First Conscription Act, passed on April 16, 1862, said that all white men between 18 and 35 years old had to serve in the military for three years. Later, on September 27, 1862, the Second Act changed the age limit to 45 years old. The Third Act, passed on February 17, 1864, made the age range even wider, from 17 to 50 years old, and said they had to serve for the entire war.

At first, if you were drafted, you could pay someone else to take your place. This rule was very unpopular and was stopped on December 28, 1863. Also, some jobs were considered "reserved," meaning people in those jobs didn't have to join the army. One controversial rule, called the "Twenty Negro Law," allowed plantation owners with a certain number of enslaved people to be exempt. This law was changed later but still caused a lot of anger because it seemed to favor the rich.

Many people argued about these laws. Some thought they gave the government too much power and took away people's freedom. Others believed these strong laws were necessary to win the war and keep the Southern states independent. Many states and individuals resisted the draft, sometimes even violently. By 1864, it became very hard for the Confederate government to enforce these conscription laws.

Contents

Why the Draft Was Needed

When the war started in April 1861, many soldiers joined the Confederate States Army. About half of them signed up for three years, but the rest only for twelve months. By December, the war was still going on, and the Confederate leaders realized they would lose almost half their army when the one-year enlistments ended in March 1862.

The Confederate Congress tried to get soldiers to re-enlist by offering rewards and time off. But General Robert E. Lee said this wasn't enough. He believed that forcing people to join the army was the only way to win the war. So, in April 1862, the Confederate Congress passed the first conscription act in American history.

Who Had to Serve

The first Conscription Act, passed on April 16, 1862, said that all white men between 18 and 35 years old had to serve in the military for three years. Soldiers who had only signed up for one year now had their service extended by two more years. The Confederate Secretary of War was in charge of deciding how many soldiers each state needed to provide.

On September 27, 1862, Congress made the age limit wider, up to 45 years old. Then, on February 17, 1864, all white men from 17 to 50 years old became eligible for military service for the rest of the war. However, those aged 17-18 and 45-50 would mostly serve in their home states for defense.

Hiring a Substitute

At first, if a man was drafted, he could pay another man to serve in his place. The person hired as a substitute had to be fit for duty and not someone who was already supposed to be drafted. This rule was heavily criticized because it seemed unfair. It meant that richer people could avoid fighting by paying someone else.

Because of the criticism, Congress finally stopped this rule on December 28, 1863. After that, on January 5, 1864, anyone who had previously hired a substitute became eligible for the draft themselves.

Jobs That Were Exempt

To keep society running and make sure weapons were still produced, a law on April 21, 1862, created a list of "reserved occupations." People in these jobs were excused from the draft. This included government officials, ministers, teachers, doctors, and workers in mines, factories, and hospitals.

On October 11, 1862, a new exemption law was passed. This law also exempted overseers on plantations that had more than 20 enslaved people. This part of the law became known as the "Twenty Negro Law." When the Third Conscription Act was passed in February 1864, it reduced the number of exempted jobs. However, even though it was very unpopular, the "Twenty Negro Law" remained in a changed form.

Electing Officers

One goal of the 1862 Act was to encourage men to volunteer. So, existing army regiments were allowed to elect their own new officers 40 days after the Conscription Act started. Men who were eligible for the draft could volunteer for a regiment of their choice and take part in these officer elections, as long as they did it within the 40 days. If they were simply drafted, they would be assigned to a regiment without having a say.

Similar rules were made for the new age groups who became eligible for service under the February 17, 1864 Act. They had a certain amount of time to form volunteer companies and elect their own officers. Those who didn't volunteer would still be organized into companies and regiments, and they would elect their own company and regimental officers.

Arguments About the Draft

The idea for a Confederate draft first came from General Robert E. Lee. With President Jefferson Davis's support, Lee had his staff write the draft law. President Davis believed that forcing men to join the army was the only way to solve the Confederate army's shortage of soldiers. He also thought it would make sure everyone shared the burden of defending the South, not just the most patriotic people.

However, not all Confederate lawmakers agreed. Some, like Senator William Simpson Oldham from Texas, argued that the draft questioned the courage of Southerners. They also worried it would lead to the government having too much power, like a dictatorship. Despite these concerns, the need for soldiers was so great that the act easily passed and became law on April 16, 1862.

Many people outside of Congress also criticized the First Conscription Act. Governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia, a strong critic of the Confederate government's power, said the Act was against the Confederate Constitution. He argued that the Constitution didn't clearly give the government the power to force everyone into military service. President Davis responded by saying that conscription was "necessary and proper" to protect the country, as the Constitution required. Other critics, like Governor John Gill Shorter of Alabama, felt that the South should only be saved by men who volunteered freely. But Senator Louis Wigfall of Texas famously said, "We must have the heavy battalions," meaning they needed a large army no matter what.

The Second Conscription Act passed quickly in Congress in September 1862. Only a few senators voted against it. The Third Conscription Act, passed in February 1864, faced even less opposition in Congress. Some even wanted an even stronger draft. However, outside of Congress, the complaints against conscription grew louder. Vice President Alexander H. Stephens and Robert Toombs declared the draft useless and unconstitutional.

The arguments over conscription were part of a bigger fight in the Confederacy. On one side were those who worried that the government was gaining too much power, seeing the draft and other actions as threats to freedom. On the other side were those who believed a strong central government was essential to protect the South from the Union armies. Most of the critics were from states like Georgia, which were far from the main fighting. Those who strongly supported the draft were often from states like Kentucky and Missouri, which were occupied by Union forces and badly divided.

Resisting the Draft

The rules allowing substitutes and the "Twenty Negro Law" caused a lot of anger among poorer Southerners. They felt it was unfair that rich people could avoid fighting. This anger spread even to soldiers in the army, causing worries about their morale. While the substitution rule was eventually stopped, the presence of white men on plantations was seen as necessary in a society that relied on enslaved labor. This was not just about keeping up production, but also about protecting white women.

The unhappiness became widespread and even reached political leaders. The North Carolina legislature wanted the "Twenty Negro Law" removed because it seemed to be a privilege for the rich. Anti-war feelings were strong in the Appalachian Mountains region of North Carolina, and the draft was a major reason for this. Even though Governor Zebulon Vance criticized President Davis, he managed to keep his state from seriously harming the war effort. The political opposition in Georgia also didn't pose a serious threat, despite Governor Brown's loud protests. He did manage to exempt all of Georgia's state officials from the draft.

From 1863, several states passed laws protecting their own state officials from the draft. North Carolina and Mississippi, for example, exempted almost every state, county, and militia officer. State courts generally supported these laws. However, attempts to free drafted men from the Confederate Army using court orders failed in all states except North Carolina. The North Carolina Supreme Court often issued orders to free drafted men, saying that state courts had the right to do so. But the Secretary of War refused to accept these court decisions.

Farmers in the Piedmont region of North Carolina found their lives severely disrupted by the draft. Three years in the army meant great hardship for their families and a risk of losing their farms. They held public meetings to protest the conscription acts. Many who were forced into the army didn't stay; they deserted in large numbers. Once back home, they formed secret self-defense groups to avoid being caught. Local home guards tried to catch deserters, but community resistance made it difficult. By the end of the war, about 12,000 North Carolinians had run away from the Confederate army.

In the poor mountain areas of the state, armed resistance groups showed their strength. While the farmers in the Piedmont still supported the Southern cause but disliked the government's extreme actions, the mountain people rejected the idea of being ruled by what they saw as a slave-owning government. Fights broke out between draft resisters and government troops, with hundreds or even thousands of resisters fighting against the Confederate Home Guards and the army.

Resistance to the draft, desertion, and armed opposition created a "civil war within the civil war" in some parts of the South. In these areas, anti-government groups controlled entire counties and fought against Confederate authority. Some joined groups that wanted peace or supported the Union. Historians say that by 1864, it was almost impossible to enforce the draft in the South. Many scholars believe that draft evasion in the South, where there were fewer men available than in the North, played a part in the Confederate defeat.

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |