David Malet Armstrong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

David Malet Armstrong

|

|

|---|---|

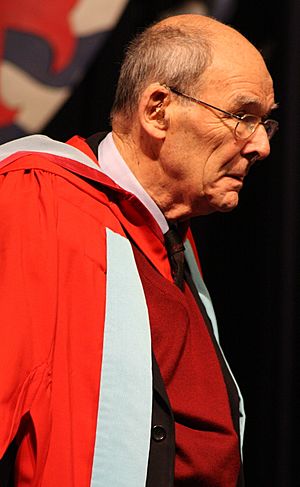

Armstrong receiving his doctorate of letters (h.c.) at Nottingham University, UK on 13 December 2007

|

|

| Born | 8 July 1926 Melbourne, Australia

|

| Died | 13 May 2014 (aged 87) Sydney, Australia

|

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy Australian realism Immanent realism Factualism Perdurantism (four-dimensionalism) |

| Academic advisors | John Anderson |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics, philosophy of mind |

|

Notable ideas

|

Instantiation principle Quidditism Maximalist version of truthmaker theory |

|

Influences

|

|

David Malet Armstrong (born July 8, 1926 – died May 13, 2014) was an important Australian philosopher. He is famous for his ideas about metaphysics (the study of what is real) and the philosophy of mind (the study of how our minds work). He believed that everything that exists is part of the physical world. He also thought that our minds are physical things, and that the laws of nature are real connections between things.

A fellow philosopher, Keith Campbell, said that Armstrong's ideas helped shape what philosophers talked about. He added that Armstrong always wanted to create a philosophy that was simple, broad, and fit well with what science tells us about the world.

Contents

Life and Career

David Armstrong studied at the University of Sydney in Australia. He then continued his studies at the University of Oxford in the UK and the University of Melbourne back in Australia.

He taught at Birkbeck College in London for a short time in 1954–55. After that, he taught at the University of Melbourne from 1956 to 1963. In 1964, he became a special professor, called the Challis Professor of Philosophy, at the University of Sydney. He stayed there until he retired in 1991.

During his career, he was also a visiting teacher at many famous universities around the world. These included Yale University, Stanford University, and the University of Notre Dame in the United States.

In 1974, the Philosophy department at the University of Sydney split into two parts. Armstrong joined the group that focused on traditional and modern philosophy. The two departments later joined back together in 2000.

Armstrong married Madeleine Annette Haydon in 1950. Later, he married Jennifer Mary de Bohun Clark in 1982 and had stepchildren. He also served in the Royal Australian Navy, just like his father, who was a high-ranking officer.

In 1950, Armstrong helped start a committee against conscription (forcing people to join the military). He did this with two friends, David Stove and Eric Dowling, who were also philosophers.

In 2014, a magazine called Quadrant published a special tribute to Armstrong. This was to celebrate 50 years since he became the Challis Professor at Sydney University.

Philosophy

Armstrong's philosophy is mostly about the natural world. He believed that "all that exists is the space-time world, the physical world as we say." He thought this was obvious, while other ideas about what exists seemed less certain. Because of this, he didn't believe in "abstract objects," like perfect ideas that exist outside our world.

Armstrong's ideas were greatly shaped by other philosophers like John Anderson and David Lewis. He also worked with C. B. Martin on essays about John Locke and George Berkeley.

Armstrong's philosophy focused on understanding reality, not on social rules or how we should act. He also didn't spend much time on the philosophy of language (how language works). He once said, "Put semantics last," meaning he thought understanding reality was more important than understanding words.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is a part of philosophy that explores what is real and how things are connected.

Universals

Armstrong believed that universals exist. Universals are properties or qualities that many different things can share. For example, "redness" is a universal because many different objects can be red. He thought these universals match up with the basic particles and forces that science tells us about. He called his philosophy a form of "scientific realism," meaning he believed in what science discovers about reality.

Armstrong thought that universals are "sparse." This means not every word we use to describe something is a universal. Only the most basic properties, discovered by science, are true universals. For example, "mass" would be a universal if physicists continue to see it as a basic property. He believed that other properties, like "being a game," are related to these basic universals in a special way.

Armstrong also believed that relations (how things are connected, like "being taller than") are universals too. He thought they could be understood in the same way as other properties.

He disagreed with ideas that said properties are just groups of things. For example, if "blue" was just the group of all blue things, it would be hard to tell the difference between "being blue" and "being wet" if everything blue was also wet. Armstrong argued that things are part of a group because they have a certain property, not the other way around.

Armstrong also said that objects have a structure. They are made of parts, which are made of molecules, then atoms, and so on. He believed that properties and relations are real parts of this structure, not just ideas in our minds.

States of Affairs

A key idea in Armstrong's philosophy is the state of affairs. You can think of a state of affairs as a "fact." It's when a particular thing (like a specific apple) has a universal property (like "redness"). So, "this apple is red" is a state of affairs.

Armstrong believed that states of affairs are the most basic parts of reality. He argued that they are more than just the sum of their parts. For example, if A is to the left of B, that's different from B being to the left of A. A state of affairs helps us understand why one is true and the other might not be.

Laws of Nature

Armstrong's ideas about universals helped him understand the laws of nature (like gravity or how light behaves). He believed that these laws are real connections between universals. For example, the law that "all ravens are black" isn't just about every single raven we've seen. Instead, it's a necessary connection between the universal "raven-ness" and the universal "blackness."

This idea helps explain laws that might not have been seen in action. For example, if a certain type of bird always died young due to a virus, that wouldn't be a law of nature. But if it was part of their basic "bird-ness" to die young, then it would be a law.

Truth and Truthmakers

Armstrong believed in a "maximalist version" of truthmaker theory. This means he thought that every true statement has something in the world that makes it true. This "something" is called a truthmaker. For example, if you say "the wall is green," the wall actually being green is the truthmaker for that statement.

He also thought that even negative statements have truthmakers. If the wall is green, that fact also makes it true that the wall is not white or not red.

Armstrong also used truthmaker theory to argue against the idea that only the present moment exists. He thought it was hard to explain what makes statements about the past true if the past doesn't exist anymore.

Mind

Armstrong believed in a physicalist and functionalist theory of the mind. This means he thought that the mind is a physical thing, and that mental states (like thinking or feeling) are just states of our central nervous system (our brain and nerves).

He was influenced by other philosophers who believed that mental states could be explained as physical events in the brain. Armstrong's book, A Materialist Theory of Mind, is considered a very important work in this area.

Epistemology

Epistemology is the study of knowledge: what it is and how we get it.

Armstrong's view of knowledge is that you know something when you have a true belief that you got in a reliable way. This means your belief was caused by something real in the outside world. He used the example of a thermometer: just as a thermometer changes to show the correct temperature, your beliefs should change to reflect what's true in the world. He believed the connection between knowledge and the world is like a law of nature.

Belief

Armstrong also thought that if you know something, you must also believe it. He disagreed with arguments that said you could know something without believing it.

He gave an example of a woman who knows her husband is dead but can't bring herself to believe it. Armstrong said she actually has two beliefs: one that he is dead (which is true and justified) and one that he is not.

Armstrong also talked about a student who is asked when Queen Elizabeth I died. The student hesitates and says "1603" without confidence. Armstrong argued that the student does believe and know the answer, but they just don't know that they know. He believed that you don't need to know that you know something in order to actually know it.

See also

In Spanish: David Malet Armstrong para niños

In Spanish: David Malet Armstrong para niños

- Moderate realism

- "The Nature of Mind"

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |