Deebing Creek Mission facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Deebing Creek Mission |

|

|---|---|

Former Deebing Creek Mission, 2004

|

|

| Location | Grampian Drive, Deebing Heights, City of Ipswich, Queensland, Australia |

| Design period | 1870s - 1890s (late 19th century) |

| Built | c. 1887 - c. 1915 |

| Official name: Deebing Creek Mission (former), Deebing Creek Aboriginal Home, Deebing Creek Aboriginal Mission, Deebing Creek Aboriginal Reserve | |

| Type | state heritage (archaeological, landscape) |

| Designated | 24 September 2004 |

| Reference no. | 602251 |

| Significant period | 1880s-1915 (historical) |

| Significant components | tank - water, trees/plantings, terracing, cemetery |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Deebing Creek Mission was a special place in Queensland, Australia, that is now listed as a heritage site. It was built between 1887 and 1915 in Deebing Heights, near Ipswich. This site was once an Aboriginal reserve, also known as the Deebing Creek Aboriginal Home or Mission. It was a place where Aboriginal people lived and worked, managed by a group called the Aboriginal Protection Association.

Contents

A Look Back: History of Deebing Creek Mission

How the Mission Started (1892)

The Deebing Creek Mission began as special areas of land set aside for Aboriginal people. The first part of this land was used as a farm to help support the Mission. Later, more land was added, and this became the main area where missionaries and Aboriginal people lived and worked.

Around 1887, a group in Ipswich called the Aboriginal Protection Association started the Mission. This group included local leaders and business people. They wanted to help Aboriginal people, but also had economic goals. The Reverend Peter Robertson, a Presbyterian minister, was in charge of this group.

At first, Aboriginal people from two main camps in the Ipswich area, one in Queen's Park and another at Purga, became the first residents of the Mission.

Who Ran the Mission?

It's not always clear which church was in charge. In 1900, school records said the children belonged to the Salvation Army. This might have been because the Superintendent, Thomas Ivins, was a Salvation Army member. A report from 1906 said a church board controlled the Mission, but the church's name was hidden.

The Aboriginal Protection Association managed the Mission, but they needed a lot of money from the government. This was especially true after the Mission was asked to take in orphaned children. In 1896, it became an "Industrial School." This meant that Aboriginal and "half-caste" children under 15 could be sent there by law.

Early Days and Life at the Mission

Reverend Edward Fuller was the first manager. He lived in a tent at first, then in a house overlooking the Aboriginal people's bark huts. The government helped by providing supplies and money.

In 1892, more land was officially set aside for the Mission. This included a special area that is now an Aboriginal Cemetery. Trustees from the Aboriginal Protection Association were put in charge of the land.

When another mission, Myora Mission, closed its school around 1896, some children were moved to Deebing Creek. They were called "orphans" and received very little money for food.

The first count of residents in 1893 showed 33 people. The number changed often because some people left for work and then came back. Before a new law in 1897, Aboriginal people at Deebing Creek could come and go freely.

The 1897 Act: A Big Change

In 1897, a new law called the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 was passed. This law greatly changed and controlled the lives of Aboriginal people. It was meant to "protect and care" for Aboriginal and "half-caste" people and to stop the sale of opium.

How the Act Controlled Lives

This Act created "Protectors of Aborigines" who oversaw the law. They received yearly reports on each mission. The law also allowed the government to create reserves and move Aboriginal people to them. It also controlled their jobs, wages, and even where they lived and moved. This meant that every part of an Aboriginal person's life could be controlled.

After 1897, this control extended to the people at Deebing Creek Mission. For example, they needed special agreements to work outside the Mission.

Aboriginal children and adults were sent to Deebing Creek from all over Queensland, even from far away places like Charleville. These people are sometimes called "historical people" because they were moved from their traditional lands. The government often did not consider that these reserves were already the traditional lands of other groups. This caused many problems for Aboriginal communities.

Life and Buildings at the Mission

In 1896, a report said that Deebing Creek Mission provided a home and food for up to 150 people. Children received a basic public school education. Aboriginal people worked by clearing land, building fences, and farming. The Mission had a main house, other buildings, and housing for Aboriginal residents.

By 1894, there were 62 Aboriginal people at the Mission and 27 attending school. Adult men had to work four hours a day on the Mission. Families were encouraged to build their own homes. By 1897, the land was fenced, and 13 cottages had been built.

A report from 1894 mentioned that the land was not very good for farming. Young men were busy fencing and clearing.

The School at Deebing Creek

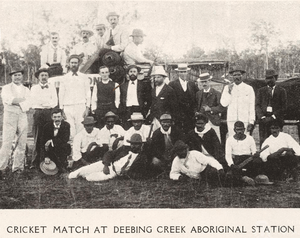

A school was set up by 1895. Its records show children's names and ages. The number of students varied, from 3 to 25. In 1895, a tent used as a schoolroom was replaced by a new building that could hold 80 people. People also played cricket there.

By December 1895, the school building was described as a simple slab building with a canvas lining. It was near the Superintendent's living area. The school was located on a specific part of the land that had been set aside for the Mission.

The 1897 Act also meant that children could be sent to the Mission as "Industrial School" children. In 1902, the Mission received money each week for each child sent there under this Act.

After the 1897 Act, regular reports were sent to the government. These reports showed how many Aboriginal people lived at the Mission and attended the school. The numbers changed often because many Aboriginal people worked outside the Mission. The highest number of residents was 150 in 1896, and the lowest was around 54 in 1913.

In 1896, the Aboriginal Protection Association bought more land next to the Mission. This was to stop new houses from being built too close together. The government's yearly funding for the Mission also increased.

Some people complained that the Mission was too close to Ipswich, making it easy for residents to get alcohol. They also said the land was not fertile enough.

Mission Improvements (1904)

Over time, improvements were made to the buildings and land. In 1904, over £250 was spent on upgrades. In 1907, a large underground water tank was built to help with the poor water supply. This tank is still there today.

A photograph from 1907 shows about 8 homes at the Mission with many people. Aboriginal people from the Mission were interested in attending and competing in a footrace in Ipswich. For this event, the law controlling their movement was temporarily stopped, as they usually needed a permit to travel outside the reserve.

By 1909, a new home was built near the school for the children who had been sent to the Mission. Farming also improved, with more animals and vegetables grown. This helped feed the residents and sometimes provided extra income for the Mission.

The 1910 report suggested that the homes and lives of those who had been at the Mission the longest had greatly improved. It said that the Aboriginal people truly made it their home.

In 1912, two new homes were built, and others were improved. The Mission controlled about 2,072 acres of land, including 200 acres at Deebing Creek.

Moving the Mission (Around 1915)

In 1914, the Deebing Creek Mission was moved to Purga. It's not completely clear what happened to all the buildings. The Aboriginal Protection Association, which had managed the Mission for 25 years, seemed to stop managing it after the move. They had spent a lot of their own money on food and clothing for the residents.

What Happened to the Land Later?

After the Mission moved, the land at Deebing Creek was no longer occupied by the Mission. By 1929, it was controlled by the Salvation Army and the Chief Protector.

In 1967, some Aboriginal people from Ipswich, led by Les Davidson, asked the Queensland Premier to protect their burial grounds, sacred sites, and cemeteries. They named two burial grounds, one at Deebing Creek Mission and one at Purga.

In the mid-1970s, there was public support for the Aboriginal people's request to have their ancestral land at Deebing Creek Mission returned. Mr. Davidson said that Aboriginal people born at Deebing Creek Mission came from many different areas.

In 1976, an area of land was officially set aside as an Aboriginal Cemetery. This cemetery is on the west bank of Deebing Creek and was part of the original Aboriginal Reserve.

There were discussions about who owned the land and how people could visit the cemetery. From 1978 to 1980, there were requests for access to land records to find out the names and burial places of the original residents of Deebing Creek Mission. There was also a plan to get more land at Deebing Creek for Aboriginal development.

In 1985, a large area of land that had been an Aboriginal Reserve since 1892 was officially changed.

What You Can See Today

The former Deebing Creek Mission site is about 8 kilometers south of Ipswich City. You can reach it from the Cunningham Highway.

Historic Plants and Trees

You can still see old trees planted a long time ago. These include a large Bunya pine tree, two big Fig Trees, a Mango Tree, and a Date Palm. These trees are important because they show where the Mission once stood.

The Underground Water Tank

The large underground brick water tank, built in 1907 to improve the water supply, is still there. It could hold 20,000 gallons of water! It's now hidden by thick plants and has an old fence around it. Sadly, it has been used as a rubbish dump.

Other Signs of the Past

You can still see signs of terracing (flat steps cut into a hillside) near the southern fence, where the land slopes down to Deebing Creek. People have also reported finding a large stone where the children at the school used to sharpen their pencils.

The Cemetery

There is one headstone at the cemetery for Mrs. Julia Ford, who died in 1896. However, stories from local Indigenous people and old reports suggest there were at least 13 more burials there. Old newspaper articles from 1892 also confirm that people who died at the Mission were buried in the nearby cemetery. You can also see the remains of stone piles that might mark other graves.

There are two old huts on the land from the Second World War. These are not from the Mission period. Local Indigenous families lived in these huts in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Deebing Creek Mission site has a lot of potential for finding old objects. Experts have found ceramics, old bottles, glass, and even a harmonica. It is known that Aboriginal residents built their homes along the banks of Deebing Creek. These houses were made of timber with dirt floors and steps leading to the creek.

Why Deebing Creek Mission is Important

The former Deebing Creek Mission is listed on the Queensland Heritage Register because it is very important to Queensland's history and culture.

It shows how Queensland's history developed. Deebing Creek Mission helps us understand how Aboriginal people were housed, made to work, and controlled in the late 1800s until it closed in 1915.

It can teach us more about Queensland's history. The old underground water tank, the historic plants, and the cemetery can help us learn more about daily life and burial customs at a mission in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It is very special to a certain community. Deebing Creek Mission is very important to the Indigenous community. It shows the lasting impact of a major historical event. It is especially meaningful to the traditional Aboriginal people of that area, and also to the "historical people" who were sent to live there. The cemetery is a significant burial ground for Aboriginal people from the Mission era.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |