Deportations from the German-occupied Channel Islands facts for kids

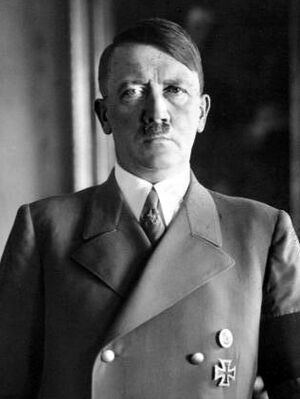

On direct orders from Adolf Hitler, German forces during World War II sent about 2,300 civilians from the Channel Islands to special camps. This was done as a way to get back at Britain for holding German citizens in Persia (now Iran).

Contents

German Takeover of the Islands

The Channel Islands, which include Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark, came under German control on June 30, 1940.

Before this, the quick German invasion of France, called the Blitzkrieg, gave the British government and the islanders a chance to leave. About 25,000 people chose to evacuate, but 66,000 stayed behind.

The British government had decided on June 15, 1940, to remove all military forces and equipment from the islands. This meant the islands were left undefended.

Through 1940 and 1941, the islanders slowly got used to living under German rule. A few people tried to escape by boat, but some did not survive the journey.

Why People Were Deported

In 1941, Persia (modern-day Iran) was a neutral country. Germany was its biggest trading partner. Britain and the Soviet Union were worried about German spies there.

In August 1941, British and Soviet forces invaded Persia. They rounded up German men living there and sent them to internment camps, mostly in India.

Adolf Hitler was very angry about this. He decided to get revenge by deporting British citizens. He wanted to deport ten British people for every German held in Persia.

German officials looked for British people in the Channel Islands. They found that about 8,000 people born in the United Kingdom lived there. By November 1941, the island authorities had to provide lists of these residents.

The Germans planned to deport about 5,000 people. However, Hitler's order to deport people was put on hold for a while.

Deportations Begin in September 1942

In September 1942, Hitler remembered his earlier order and demanded it be carried out. Things moved very fast on the islands.

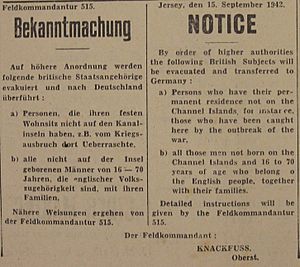

On September 15, 1942, the order arrived in Jersey. Notices were put in local newspapers. Island officials refused to deliver the deportation orders. So, German soldiers, guided by local officials, delivered the orders that evening.

People were told they could only take what they could carry. They had no time to sort out their homes or businesses. Valuables were left in banks. Pets had to be given away or put down. Some women quickly married their local fiancés to avoid being deported.

Some deals were made to allow certain people to stay. For example, many church ministers were English, so enough were allowed to remain to continue church services. People who were useful to the Germans for their work, or those who were very sick or old, were also sometimes spared.

Leaving the Islands

The Germans hoped to deport many people at once. On September 16, 1942, only 280 men, women, and children left Jersey on the first ship. Crowds lined the streets, crying and waving goodbye. The islanders gave them food for their journey. Many former soldiers proudly wore their medals. As the ship sailed, people sang patriotic songs.

Two days later, more ships were ready in Jersey. About 600 more people were told to report. One ship was very dirty from carrying coal, so island officials refused it. Only 346 people sailed that day. Those who couldn't leave returned home, only to find their houses had been emptied. The crowds waving goodbye were even larger this time. Their patriotic singing angered the Germans, leading to violence and arrests.

Ships left Guernsey on September 26 and 27 with 825 deportees, including 9 from Sark. Guernsey borrowed German field kitchens to cook a meal for the "evacuees," as the Germans called them. A third group of 560 left Jersey on September 29, 1942. This sailing also led to large crowds, singing, and more arrests.

Instead of crowded boxcars, the Germans gave the deportees second-class train carriages. The journey to the camps took three days.

February 1943 Deportations

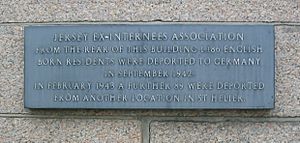

A British commando raid on Sark in October 1942, called Operation Basalt, led to another round of deportations in February 1943. People were taken from all three islands. Out of 1,000 eligible people, 201 were deported.

This group included eight Jewish people from Guernsey and Jersey. Despite being sent to harsh camps like Buchenwald concentration camp, they all survived the war.

A few weeks after the deportations began, some very sick people were secretly returned to their islands.

Internment Camps

The Channel Islanders were sent to several internment camps in Germany. These were not prisoner-of-war camps for soldiers, but camps for civilians.

Dorsten

Stalag VI-J was a transit camp in Dorsten, a busy industrial area. The camp was surrounded by balloons to protect against bombing. The camp leader, known as 'Rosy Joe,' even bought milk for the children with his own money. Islanders from Guernsey and some from Jersey stayed here for six weeks. Later, single men went to Laufen, while families went to Biberach and Wurzach. Dorsten stopped being used for internees after November 1942.

Biberach

Oflag V-B, later renamed Ilag V-B, was in Biberach an der Riß in southern Germany. It had views of the Bavarian Alps. This camp was also known as Lager Lindele.

The first groups from Jersey arrived at what used to be a Hitler Youth summer camp. It had 23 huts surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers. Each hut held 84 people in rooms meant for 18. Men were kept separate from women and children. There were also hospital huts, a canteen, and washing areas. A school was set up in one hut. Conditions improved after complaints were made in late 1942.

In late 1942, single men were sent to Laufen, and some families went to Wurzach. This made space for families from Dorsten. About 1,011 internees remained, mostly Channel Islanders. More people arrived with the February deportations, including some Jewish people and Arabs.

A nurse from Guernsey, Gladys Skillett, gave birth in Biberach. She was the first Channel Islander to have a baby while held captive in Germany. Mothers were not happy that the birth certificates had a swastika stamp.

Wurzach-Allgau

Now called Bad Wurzach, ‘Ilag V-C’ was a smaller camp about 30 miles south of Biberach. It had also been an officers' camp before. In October 1942, 618 Channel Islanders were moved here from Biberach. More arrived in November from Dorsten. They lived in the Schloss, a large 17th-century mansion that had been a Catholic college. They had to clean the dirty buildings within a week.

The Schloss had a hospital, a theater, and rooms for men and women. Some families with small children had private rooms. A school was set up for the 130 children, but there were no qualified teachers.

Red Cross visitors were not happy with the living conditions, even though the Germans provided coal for fires when visits were expected. The camp was crowded, damp, and had rats, mice, and fleas. Few changes were made, except for better sanitation.

In late 1944, 72 Dutch Jewish people arrived from Bergen-Belsen. The deportees then learned firsthand about the terrible conditions in other camps.

Laufen

Ilag VII in Laufen, Bavaria, was a camp for single men. It was a Schloss (castle) with many floors. Men over 16 from Dorsten and Biberach were sent here. Ambrose Sherwill became the camp leader in June 1943. A few American civilians were already there. Men found it easier to adapt to camp life, but hunger and boredom caused problems.

The internees did not receive Red Cross parcels before Christmas 1942. A nearby POW camp generously gave each person in Laufen a tin of condensed milk and biscuits. Letters home often mentioned how cold the castle was.

Like other camps, Laufen had its own fire brigade, canteen, tailors, and shoemakers. The YMCA provided 1,500 books for a library. With 27 teachers among them, classes were set up in five languages and 33 subjects. Sports and entertainment were also organized.

Boredom was a big problem. Some internees were allowed to work outside the camp for pay. There was much debate in the camp about whether it was right to work for the Germans.

Life in the Camps

All camps were run by the military at first. There were daily inspections and three roll calls every day. In December 1942, Biberach and Wurzach were taken over by the police, who understood the needs of mothers and children better than soldiers.

Each camp had a main leader, called a “Lagerführer.” Each hut also had an elected leader. Everyone had daily duties, from cleaning to working in the hospital or as a barber or electrician. Biberach even had its own camp police force.

Internees mostly slept in wooden bunk beds with straw mattresses, a pillow, and army blankets. They had lockers and shared showers. Huts were locked at night. In Biberach and Wurzach, men, women, and children could spend time together during the day.

Food was often not enough. They usually had watery soup twice a day and a 1 kg loaf of bread shared among five people daily. Red Cross parcels started arriving in mid-October 1942. This greatly improved their nutrition. Each person received one parcel per week until December 1944, when German transport systems began to fail. These parcels contained milk, fruit, jam, fish, and soap. Christmas parcels even included pudding and marzipan sweets.

The YMCA and YWCA regularly visited, providing instruments, sheet music, and art supplies for entertainment. Camp shows and musical events were common. Sports days were held regularly, with football, hockey, and cricket matches. Church services and schools for children were also set up.

Internees created "camp art" like engraving tin mugs, sewing, making Christmas toys, and sandals from string. The Red Cross also supplied seeds for gardens.

Long walks (up to 10 miles) and shorter walks were allowed outside the Wurzach camp, with guards. People on walks would trade Red Cross goods for food like rabbits, chickens, and eggs. They also collected wild food.

A postcard system allowed them to send messages to the UK (through the Red Cross) and the Channel Islands (through German mail). Internees could send three letters and four postcards a month. Letters could be as long as they wanted. Each camp had censors.

Internees received 10 marks a month to buy extra items. Men were allowed to cut trees for firewood. The cold and damp were big problems, especially when temperatures dropped to -20°C. Sickness from poor food, diphtheria, and scarlet fever caused some deaths.

Hidden radios in all three camps allowed internees to listen to BBC news. They also knew about the war from bombers flying overhead and new arrivals who had seen bombed cities. In one camp, a man put up a map and tracked Allied army progress with red wool.

In September 1944, 125 elderly and sick people were sent back to the UK via Sweden. In April 1945, another 212 people, including 24 from Laufen, were sent home.

Boredom and the same routine were major problems. Special events became very memorable. Laufen men visited a traveling circus and got their own cinema projector to show borrowed films. In January 1945, a traveling cinema came to Wurzach, and many children saw a movie for the first time.

When Red Cross parcels arrived in large numbers, those in the camps were probably better fed than most people left on the occupied islands. Some internees even sent Red Cross parcels to the Channel Islands.

Freedom at Last

Biberach town was bombed on April 12, 1945. On April 22, French tanks passed by. The next day, with German permission, a detainee cycled to the French army and told them the town was open. The French arrived, the Germans retreated, and the camp was freed on St. George's Day (April 23). On May 29, 1945, 1,822 people, including 160 children, were flown to England.

Wurzach was freed on April 28, 1945, by a French Moroccan armored unit. They didn't know about the internees. The Germans quickly surrendered, avoiding bloodshed. The internees left the camp in early June and were flown to the UK on June 7.

Laufen was the last camp to be freed, on May 4, 1945, by American soldiers. They saw a British flag painted on a sheet and came to investigate. Many men spent the next month helping local hospitals care for victims from concentration camps. The town of Laufen waved goodbye as they left for the airfield in June.

Some children were born in the camps and walked out to freedom when the war ended. It took several months for the authorities in England to give everyone ration cards and ID cards. Some returned to Guernsey in August.

Deaths in the Camps

Sadly, some internees died in the camps. Three died in Dorsten, twelve in Wurzach, and twenty in Biberach (not counting others whose deaths were not recorded). Ten people died in Laufen. Ten of the deaths were females, and five were children. Up to 20 internees were allowed to attend each funeral in the local churchyards.

See also

- Channel Islands Occupation Society

- German occupation of the Channel Islands

- History of the Jews in Guernsey

- History of the Jews in Jersey

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |