Dignāga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dignāga |

|

|---|---|

A statue of Dignāga in Kalmykia

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | |

| Education | |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 470/480 CE Near Kanchi |

| Died | c. 530/540CE |

| Religious career | |

| Students |

|

Dignāga (born around 470-480 CE, died around 530-540 CE) was an important Buddhist thinker from ancient India. He was a philosopher and a master of logic. People remember him as one of the first Buddhist thinkers to create a system for Indian logic. He also helped develop the idea of atomism in Buddhism.

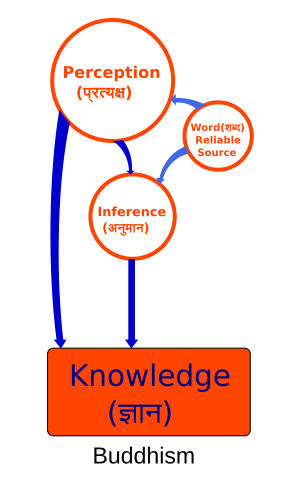

Dignāga's ideas helped shape how people thought about logic and how we gain knowledge. His work became very important in India and Tibet. His teachings also influenced later Buddhist philosophers and even Hindu thinkers. He believed we gain true knowledge in only two ways: through "perception" (seeing or sensing things directly) and "inference" (figuring things out through reasoning). His ideas about language and how we understand words were also very influential.

Contents

The Life of Dignāga

We don't know much about Dignāga's early life. He was born into a Brahmin family near the city of Kanchi in India. This was around the years 470 or 480 CE.

When he was young, he became a Buddhist monk. Later in his life, he was connected to the famous Nalanda monastery. This monastery was a very important center for learning in ancient India.

Dignāga's Philosophy

Dignāga's main ideas are found in his most important book, the Pramāṇa-samuccaya. In this book, he explains his ideas about how we get knowledge. He said there are only two ways to gain true knowledge. These are "perception" (pratyakṣa) and "inference" (anumāna).

He wrote that these two ways are the only ones because there are only two kinds of things we can know. One is a unique, specific thing. The other is a general idea. He explained that perception helps us know specific things. Inference helps us understand general ideas.

Perception is about directly sensing things without thinking too much about them. Inference, on the other hand, involves thinking, using language, and making connections. Dignāga's ideas were different from other schools of thought at the time. Some other schools believed there were more ways to gain knowledge, like comparing things.

What is Perception?

Perception (pratyakṣa) is when our senses directly take in information about specific things. This is the main topic of the first part of his book. For Dignāga, perception is like raw information. It comes before we add words or ideas to it. It's just the pure sense data.

He explained that our minds naturally try to organize this raw sense data. We give things names, group them, and compare them to past experiences. This process is called kalpana. But true perception is just the simple, immediate sensing. For example, seeing a patch of green color is perception. Thinking "that's an apple" is already a higher level of thinking.

Dignāga also believed that pure perception cannot be wrong. It's the most basic way we experience things. Mistakes happen when our minds misinterpret or add ideas to what we perceive.

What is Inference?

Inference (anumāna) is a way of knowing that deals with general ideas. It's built from simpler perceptions. We can also share our inferences using language.

Dignāga was very interested in how we use signs or evidence to make an inference. For example, how does seeing smoke lead us to believe there is a fire? He discussed how we make inferences for ourselves. He also talked about how we explain our inferences to others through arguments.

According to Dignāga, to know that a certain quality is present in something, you need an "inferential sign." This sign must meet three conditions:

- The sign must be present in the thing you are observing.

- The sign must also be found in other places where the quality you are inferring is present.

- The sign must never be found in places where the quality you are inferring is absent.

These rules are very strict. Dignāga believed that logic helps us avoid being too sure about our opinions. He thought that very few of our everyday judgments would pass these strict tests. This means we should always be open to changing our minds if we learn new things.

Language and Exclusion

Dignāga believed that understanding words and sentences is a special kind of inference. He discussed how language works in his book.

Many thinkers at his time believed in "universals." These are ideas that a single concept (like "cow-ness") exists for all cows. But Dignāga, like many Buddhist thinkers, did not believe in universals. Instead, he developed a theory called "apoha" (exclusion).

This idea says that a word doesn't describe something real directly. Instead, it tells us what something is not. For example, the word "cow" doesn't point to a universal "cow-ness." It simply means "not a non-cow." So, understanding a word is like making an inference by ruling out other possibilities.

Dignāga's Writings

It's hard to study Dignāga's original writings today. This is because none of his books have survived in their original Sanskrit language. We only have translations in Tibetan and Chinese. These translations can be difficult to understand.

Because of this, scholars often study Dignāga through the works of later thinkers who commented on his ideas. However, these later thinkers sometimes added their own new ideas.

Pramāṇa-samuccaya

Dignāga's most famous work is the Pramāṇa-samuccaya, which means Compendium of Epistemology. In this book, he explored perception, language, and reasoning. He described perception as a simple, direct knowing. He saw language as useful tools we create by excluding other things.

The book has six chapters:

- Chapter one is about perception.

- Chapter two is about making inferences for yourself.

- Chapter three is about explaining inferences to others.

- Chapter four discusses reasons and examples.

- Chapter five deals with the idea of "exclusion" (apoha).

- Chapter six talks about comparisons.

Today, scholars are working to put together the original Sanskrit text of this book. They are doing this by looking at old commentaries that quote Dignāga's words.

Other Known Works

Dignāga wrote many other books on logic and how we gain knowledge. Some of them include:

- Alambana-parīkṣā (Examination of the Object of Cognition): This book argues that the objects we perceive are not truly real. It suggests that only consciousness is real.

- Hetucakraḍamaru (The Reason Wheel Drum): This was one of his first works on formal logic. It helped connect older ideas about reasoning with his newer theories.

- Nyāya-mukha (Introduction to Logic): This book was translated into Chinese by famous travelers like Xuanzang.

He also wrote other works that were more about religious topics or Buddhist scriptures:

- Abhidharmakośamarmapradīpa: A summary of another important Buddhist text called the Abhidharmakosha.

- Prajñāpāramitāpiṇḍārtha: A summary of a Mahayana Buddhist text about the "Perfection of Wisdom."

Some of Dignāga's works are now lost.

Influence and Legacy

Dignāga started a very important tradition of Buddhist thinking about how we gain knowledge and use logic. This school is sometimes called the "School of Dignāga." It was greatly influenced by another philosopher named Dharmakirti. In Tibet, this school is known as "those who follow reasoning."

Dignāga's ideas also influenced the Madhyamaka school of Buddhism. Thinkers like Śāntarakṣita used Dignāga's logic to support Madhyamaka teachings.

Dignāga's tradition of logic continued to grow in Tibet. Important Tibetan thinkers like Sakya Pandita further developed these ideas.

His work also had a big impact on non-Buddhist thinkers in India. After Dignāga, many Indian philosophers felt they needed to explain how they gained knowledge. They had to defend their ideas using a clear theory of knowledge.

See also

In Spanish: Dignāga para niños

In Spanish: Dignāga para niños

- Hetucakra

- Trairūpya

- Buddhist logic

- Critical Buddhism

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |