Domnall mac Eimín facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Domnall mac Eimín meic Cainnig

|

|

|---|---|

| Mormaer of Mar | |

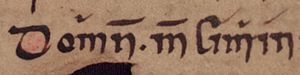

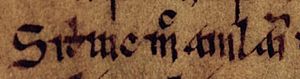

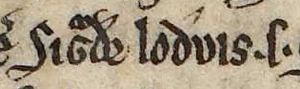

Domnal's name as it appears on folio 36v of Oxford Bodleian Library Rawlinson B 489 (the Annals of Ulster).

|

|

| Died | 23 April 1014 Clontarf |

Domnall mac Eimín meic Cainnig (died 23 April 1014) was an important leader in Scotland around the year 1000. He was known as the Mormaer of Mar. A mormaer was a powerful ruler, similar to an earl, who looked after a large area of land called a province. Domnall is the very first Mormaer of Mar that we know about from historical records.

Domnall is famous for fighting and dying in a huge battle in Ireland called the Battle of Clontarf. This battle happened on April 23, 1014. He fought alongside Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, High King of Ireland, who was a very powerful king. Their enemies were the forces of Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, King of Dublin, Máel Mórda mac Murchada, King of Leinster, and Sigurðr Hlǫðvisson, Earl of Orkney. Domnall is the only Scottish fighter specifically mentioned in the records of this battle.

Contents

Domnall's Life and Role

Domnall might have had family roots from the Vikings. His father's name, Eimín, could be a Gaelic version of the Old Norse name Eyvindr. Domnall was the Mormaer of Mar, a region in what is now Aberdeenshire, Scotland. This area was very important in the early Kingdom of Alba, which was an old name for Scotland. The records that talk about Domnall are also the first times the province of Mar is mentioned in history.

The word mormaer (plural mormaír) is a Gaelic title. It might mean "sea steward" or "great steward." In Scotland, mormaers were very important officials, almost as powerful as the king. They were like managers or governors of a province. In times of peace, a mormaer would manage their land. During war, they would lead the army from their province. Later, this title became more like an "earl" in English.

The Battle of Clontarf

In 1014, Domnall fought and died at the Battle of Clontarf. He was helping Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, the High King of Ireland. Brian's army fought against a group of allied forces. These included the King of Dublin, the King of Leinster, and the Earl of Orkney. Brian's side won the battle, but it was a very costly victory. Both sides lost many fighters, and Brian himself was killed. His goal of taking over Dublin was not fully achieved.

Many old historical books and stories mention Domnall's part in this battle. These include the Annals of Clonmacnoise, the Annals of Loch Cé, and the Annals of Ulster. Another important story is found in a book called Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib. It's interesting that one major Irish record, the Annals of Inisfallen, does not mention Domnall.

Domnall seemed to be one of the main leaders in Brian's army. He might have led a group of fighters from other countries. The enemy forces were led by Máel Mórda and Sigurðr. King Brian did not fight in the battle himself.

Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib says that Brian's army had three main groups. One group, on the left side, included ten mormaers and their Viking allies. Domnall was one of the few well-known leaders in this group. This suggests that his unit was mostly made up of Viking fighters.

Domnall's Death in Battle

The most accurate stories about the battle come from old Irish records. Some later stories, like Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib, might have added legends. Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib was probably written to make Brian's family look good. It might have made Domnall's role seem bigger to show good connections between Ireland and Scotland.

However, Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib is the only source that gives many details about the battle. It says Domnall played a very important part. The story tells that the night before the battle, a fighter named Plait, who was the son of a Viking king, bragged that no one in Ireland could beat him. Domnall said he was ready for the challenge.

The next day, when the armies were ready, Plait called out Domnall's name. The two fought each other and both died. So, according to this story, they were the first fighters to clash at the Battle of Clontarf. This duel between Domnall and Plait is a whole chapter in the book. It's not certain if this duel really happened exactly as described. It might have been a way to settle an old disagreement between them.

Some of the words used by Domnall and Plait in Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib are a mix of Gaelic and Old Norse (the Viking language). For example, when Plait asks "Faras Domnall?", the word faras is like the Old Norse "hvar es," meaning "where is." When Domnall calls Plait a sniding, it's like the Old Norse niðingr, meaning "wretch" or "scoundrel." This suggests that they might have been able to speak both languages.

The story also says that Domnall delivered a message from King Brian to Brian's son, Murchad. Brian told Murchad not to go too far ahead of his troops. Murchad said he wouldn't back down. Domnall then promised he would also fight bravely. The story says Domnall kept his promise. This shows Domnall as a loyal and brave follower of King Brian.

Why Domnall Fought

Domnall is the only person from Scotland specifically recorded as dying at the Battle of Clontarf. We don't know if other Scottish leaders were there. Domnall's presence shows that this battle was not just between Irish groups; it involved people from different countries. This might show that King Brian was good at making alliances.

We don't know exactly why Domnall fought. He might have been a hired fighter, or perhaps a nobleman who had to leave Scotland. If he had been raised by an Irish family, he might have felt a duty to fight with them.

Some stories suggest that King Brian collected taxes from areas around the Irish Sea, including parts of Scotland. If this is true, it could explain why Domnall was there. In 1005, a new king, Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, took the throne in Scotland. That same year, King Brian gave money to a very important church in Armagh, Ireland. He was called Imperator Scottorum (Emperor of the Scots) in a Latin book. This title might mean he claimed power over not just the Irish, but also Vikings in Ireland and Scots in Alba. It's not clear if this title is connected to Domnall being at the battle, but it could explain a Scottish presence.

It's also possible that Domnall's involvement was due to problems within the Scottish royal family. His fighting at Clontarf could mean that a group in Scotland, wanting to become king, joined forces with Brian. They might have recognized Brian's power to help their own goals. Not much is known about King Máel Coluim's rule. Some records suggest that other families, like the Clann Ruaidrí from Moray, challenged his power.

Even though King Máel Coluim did not fight at Clontarf, some people connected to him might have been involved. For example, some stories say Máel Coluim's mother was from Leinster (an Irish region). Also, the Earl of Orkney, Sigurðr, who fought against Brian, was said to be married to Máel Coluim's daughter. Sitriuc, the King of Dublin, also had a mother from Leinster.

We don't know which side the people of Mar usually supported. It's unclear if Domnall's fighting for Brian meant King Máel Coluim supported Brian, or if Domnall acted on his own. King Máel Coluim might have been worried about the growing power of the Vikings and the Earl of Orkney. He might have stayed neutral in their fight against Brian.

The family ties between King Máel Coluim, Sigurðr, and Sitriuc suggest that Máel Coluim might have been more likely to side with them against Brian. So, Domnall's support for Brian might have been a reaction to this alliance. The fact that Domnall risked and lost his life for Brian could mean he was against Sigurðr and Máel Coluim.

One reason why some foreign fighters joined Brian was a growing concern about Sigurðr's power. This threat might have pushed King Máel Coluim to send Domnall to help Brian. If Domnall was indeed fighting for Máel Coluim, and if Máel Coluim's family was from Leinster, then Domnall's support for Brian could also have been part of a bigger family rivalry in Ireland.

Images for kids

-

Domnal's name as it appears on folio 36v of Oxford Bodleian Library Rawlinson B 489 (the Annals of Ulster).