Dorr Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dorr Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

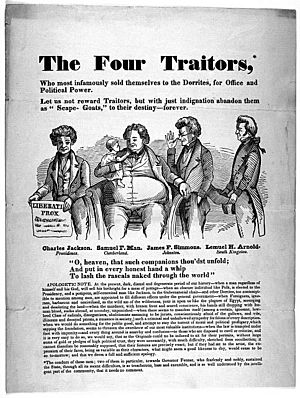

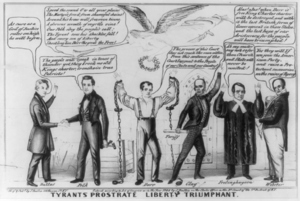

A polemic applauding Democratic support of the Dorrite cause in Rhode Island, 1844 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Samuel Ward King | Thomas Wilson Dorr | ||||||

The Dorr Rebellion (1841–1842) was a time when many people in Rhode Island fought for the right to vote. At this time, only a small group of rich landowners controlled the government. The rebellion was led by Thomas Wilson Dorr. He helped people who couldn't vote demand changes to the state's voting rules.

Rhode Island was still using an old rulebook from 1663, called a "colonial charter," as its constitution. This old rulebook said that only men who owned land could vote. The rebellion created its own government and wrote a new constitution for Rhode Island. Even though the rebellion was stopped by force, it made the state change its constitution to let more people vote.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

Back in 1663, when Rhode Island got its colonial charter, only men who owned land could vote. At that time, most people were farmers and owned land, so this rule seemed fair. But by the 1840s, things had changed a lot.

Voting Rules and Changes

The state still required men to own land worth at least $134 to vote. This was a lot of money back then. As the Industrial Revolution grew, many people moved from farms to cities. They worked in factories and didn't own land. Because of this, they couldn't vote.

By 1829, about 60% of white men in Rhode Island couldn't vote. Women and most non-white men were also not allowed to vote. Many of the people who couldn't vote were new Irish Catholic immigrants. They lived and worked in cities and earned salaries, but they didn't own land.

Calls for Fairer Voting

People who wanted more voting rights argued that the old system was unfair. They said that a system where only 40% of white men could vote, based on a rulebook from a British king, wasn't truly American. They believed it went against the Constitution of the United States, which says each state should have a "republican" (or representative) form of government.

Before the 1840s, people tried many times to replace the old colonial charter. They wanted a new state constitution that would give more people the right to vote. But all these attempts failed. The state didn't have a clear way to change its old rulebook. The state's government, controlled by landowners, kept refusing to expand voting rights. They also didn't create a bill of rights or update how representatives were chosen, even though cities had grown much larger.

By 1841, most other states in the U.S. had removed property rules for voting. Rhode Island was one of the few states that still had strict limits on who could vote.

The Rebellion Itself

In 1841, people who wanted voting rights, led by Thomas Dorr, decided to try a new approach. They stopped trying to change the system from the inside.

Two Constitutions

In October 1841, Dorr's supporters held their own meeting. They wrote a new constitution, called the "People's Constitution." This new plan would let all white men vote if they had lived in the state for one year. Dorr had first supported voting rights for Black men, but he changed his mind in 1840. This was because white immigrants wanted to get the vote first.

At the same time, the state's official government also held a meeting. They wrote their own constitution, called the "Freemen's Constitution." This one offered some small changes to voting rules.

Later that year, people voted on both constitutions. The official "Freemen's Constitution" was rejected by the state government, mostly because Dorr's supporters voted against it. But the "People's Constitution" was strongly supported in a public vote in December. Many of the people who voted for it were those who would get the right to vote under the new plan. Dorr claimed that even most people who could already vote also supported it, making it legal.

Two Governors

In early 1842, both groups held their own elections. This led to two men claiming to be the Governor of Rhode Island in April: Thomas Dorr and Samuel Ward King. Governor King, who supported the old system, refused to accept the new constitution. When things got tense, he declared "martial law," which meant the military took control.

On May 4, the state government asked the U.S. President, John Tyler, to send federal troops. President Tyler sent an observer. He decided not to send soldiers because he felt the danger was decreasing. However, he said that if the laws of Rhode Island were resisted by force, the U.S. government would have to step in.

Most of the state's citizen soldiers were Irishmen who had just gained voting rights under Dorr's plan. They supported Dorr. Irish groups in other states also supported Dorr with words, but they didn't send money or men.

The Attack and Retreat

On May 19, 1842, Dorr's supporters tried to attack an arsenal (a place where weapons are stored) in Providence, Rhode Island. People defending the arsenal, who supported the old charter, included Dorr's own father and uncle. Also, many Black men who had supported Dorr earlier were among the defenders. Dorr's cannon didn't fire, no one was hurt, and his army quickly left.

After this defeat, Dorr went to New York. He came back in late June 1842 with armed supporters. They gathered on Acote's Hill in Chepachet. They hoped to restart their People's Convention there. Governor King then called out the state's citizen soldiers, who marched towards Chepachet to fight Dorr's forces.

Dorr realized he would lose the battle against the approaching soldiers. He told his forces to disband and fled the state. Governor King offered a $5,000 reward for Dorr's arrest.

What Happened Next

The people who supported the old charter finally understood that many people wanted voting rights. They called for another meeting. In September 1842, the Rhode Island government met and wrote a new state constitution. This new constitution was approved by the old, limited group of voters. Governor King announced it on January 23, 1843, and it started in May.

New Voting Rights

The new constitution made voting much easier. It allowed any native-born adult man to vote, no matter his race. The only requirement was that he had to pay a small poll tax of $1. This money would help support public schools. However, the constitution still required non-native born citizens to own property to vote. It also stopped members of the Narragansett Indian Tribe from voting.

The changes had a big impact. In the next Presidential election in 1844, 12,296 votes were cast. This was a big jump from the 8,621 votes in 1840.

In a court case called Luther v. Borden (1849), the Supreme Court of the United States said that people have a right to change their government. But the court also said it couldn't get involved in this specific situation. They felt it was a "political question" that should be handled by other parts of the government.

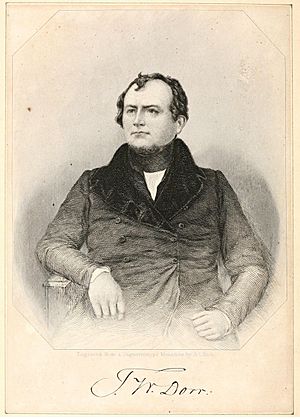

Thomas Dorr's Story

Thomas Dorr came back to Rhode Island in 1843. He was found guilty of trying to change the government by force. In 1844, he was sentenced to solitary confinement and hard labor for life. Many people thought this punishment was too harsh. Dorr was released in 1845, but his health was broken. His rights as a citizen were given back to him in 1851. In 1854, the court decision against him was canceled. He died later that same year.