Edward Schunck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

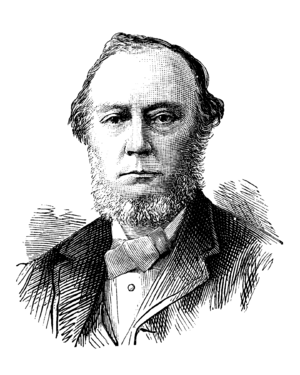

Edward Schunck

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 16 August 1820 Manchester, Lancashire, England, UK

|

| Died | 13 January 1903 (aged 82) Kersal, Broughton, Salford, Lancashire, England, UK

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin, University of Gießen |

| Known for | work with dyes |

| Awards | Dalton Medal (1898) Davy Medal (1899) |

| Scientific career | |

| Doctoral advisor | William Henry, Justus Liebig |

Henry Edward Schunck (born August 16, 1820 – died January 13, 1903) was a British chemist. He was also known as Edward von Schunck. He spent much of his career studying and working with dyes, which are substances used to color things like fabric.

Contents

Early Life and Learning Chemistry

Henry Edward Schunck was born in Manchester, England. His father, Martin Schunck, was a merchant from Germany. Edward began his chemistry studies in Manchester with a chemist named William Henry.

Later, young Edward traveled to Berlin to continue his studies. There, he learned from Heinrich Rose, a chemist who discovered the element niobium. He also studied with Heinrich Gustav Magnus, who wrote many papers on chemistry and physics. After his time in Berlin, Edward earned his PhD from the University of Gießen under the famous chemist Justus Liebig.

Discoveries in Chemistry

Edward Schunck published his very first research paper in 1841. It was about how nitric acid reacted with a plant extract called aloes. He found that this reaction created a new substance called chrysammic acid.

Exploring Dye-Producing Plants

Schunck became very interested in natural dyes. He studied lichens, which are tiny plant-like growths that can produce purple colors. These colors, like orchil and cudbear, were important for making dyes.

In 1842, Schunck discovered a new compound from lichens called lecanorin. Today, we know it as lecanoric acid. He also found another new compound, parellic acid, from a different type of lichen.

Studying Madder Dye

In 1842, Schunck returned to Britain and started working in the chemical industry. He began studying madder, a very important red dye. In the 1860s, Britain imported a lot of madder.

Schunck investigated the main coloring part of madder, which is called alizarin. He found that alizarin could be changed into other substances. His work helped other chemists later figure out how to make alizarin in a lab, which was a big step for the dye industry.

Schunck also discovered that the fresh madder root didn't contain much alizarin directly. Instead, it had a yellow substance he named rubian. Rubian was a mixture of compounds that could turn into alizarin and sugar when treated with acids or certain enzymes. He identified many other related compounds from madder.

Researching Indigo Dye

Around 1855, Schunck started focusing on indigo, a famous blue dye. He grew a plant called woad, which was used to make indigo. He extracted a substance he called "indican" from the woad plant. This "indican" was the raw material for the blue dye.

Schunck also looked into why indigo-like substances sometimes appeared in human urine. He believed it was more common than people thought. He tested urine from many people and found that most had this substance. He even experimented with his own diet to see if it changed the amount of indigo in his urine. He found that eating a mix of treacle and arrowroot made a lot of indigo appear!

His Life and Contributions

Edward Schunck married Judith H. Brooke in 1851 and they had four children. Before he retired, he worked in the business of printing patterns on fabric, known as calico printing.

He was the president of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society for several years. He was also honored by the Royal Society and the Society of the Chemical Industry for his important work.

Edward Schunck's Legacy

Schunck built his own private chemistry lab at his home in Kersal. When he passed away, he gave this lab, along with his books and chemical samples, to the Victoria University of Manchester. He also donated a large sum of money to the university to support chemical research.

In 1904, his laboratory was moved from his home and rebuilt at the university. This building is now named the Schunck Building in his honor. The room where he kept his library is very fancy. His books are now kept at the John Rylands University Library, and his chemical samples are at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |