Elinor Wylie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elinor Wylie

|

|

|---|---|

Elinor Wylie

|

|

| Born | Elinor Morton Hoyt September 7, 1885 Somerville, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | December 16, 1928 (aged 43) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, editor |

| Language | English |

| Notable works | Nets to Catch the Wind, Black Armor, Angels and Earthly Creatures |

| Notable awards | Julia Ellsworth Ford Prize |

| Spouse |

Philip Simmons Hichborn

(m. 1906; died 1912)Horace Wylie (m. 1916–19??) William Rose Benét

(m. 1923) |

| Children | Philip Simmons Hichborn, Jr. |

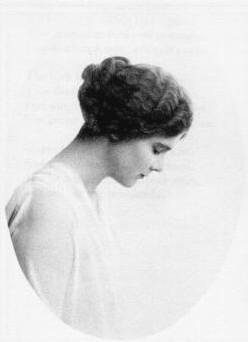

Elinor Morton Wylie (born September 7, 1885 – died December 16, 1928) was an American poet and novelist. She was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. People knew her for her beautiful writing and her charming personality.

Contents

Elinor Wylie's Life Story

Her Family and Early Years

Elinor Wylie was born Elinor Morton Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey. She came from a well-known family. Her grandfather, Henry M. Hoyt, was a governor of Pennsylvania. Her father, Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr., worked for the United States government. He was the Solicitor General of the United States from 1903 to 1909. This job means he was a top lawyer for the government.

Elinor had several brothers and sisters:

- Henry Martyn Hoyt III (1887–1920), an artist.

- Constance Hoyt (1889–1923).

- Morton McMichael Hoyt (1899-1949).

- Nancy McMichael Hoyt (1902-1949), who wrote books. She also wrote a book about Elinor Wylie.

In 1887, Elinor's family moved to Rosemont, a town near Philadelphia.

Because her father was involved in politics, Elinor spent much of her childhood in Washington, D.C. She went to several schools, including Miss Baldwin's School and Holton-Arms School. From age 12 to 20, she lived in Washington, D.C., again. She was trained to be part of the city's important social events.

Her Writing Career

Elinor Wylie's friends, who were also writers, encouraged her to send her poems to Poetry magazine. In May 1920, Poetry published four of her poems. One of these was "Velvet Shoes," which became very famous.

In 1921, Elinor Wylie moved to New York. That same year, her first book of poetry, Nets to Catch the Wind, was published. Many critics still think this book has her best poems. It was an instant success. Famous poets like Edna St. Vincent Millay praised her work. Elinor won the Julia Ellsworth Ford Prize for this book.

In 1923, she published Black Armor, another successful book of poems. The New York Times said it was perfect, with "not a misplaced word."

Also in 1923, Wylie's first novel, Jennifer Lorn, came out. It was celebrated with a lot of excitement. Some people even held a parade in Manhattan to celebrate its release!

Elinor Wylie was known for her sharp mind. Her novels were described as beautiful stories with deep, clever ideas.

She worked as the poetry editor for Vanity Fair magazine from 1923 to 1925. She also worked as an editor for Literary Guild and The New Republic from 1926 to 1928.

Wylie greatly admired the British Romantic poets, especially Percy Bysshe Shelley. She even wrote a novel in 1926 called The Orphan Angel. In this story, a young poet is saved from drowning and travels to America.

By the time her third poetry book, Trivial Breath, was published in 1928, Elinor and her husband, William Rose Benét, decided to live apart. She moved to England. There, she wrote a series of 19 sonnets (a type of poem). She published these privately in 1928 as Angels and Earthly Creatures. These poems were also included in her 1929 book of the same name.

Elinor Wylie's writing career lasted only eight years. But in that short time, she wrote four books of poems, four novels, and many magazine articles.

Her Death

Elinor Wylie had very high blood pressure throughout her adult life. This caused her to suffer from severe headaches. She died from a stroke at her husband's apartment in New York. She was only forty-three years old. At the time, she was getting her book Angels and Earthly Creatures ready for publication.

Elinor Wylie's Writing Style

Her Poetry

Elinor Wylie's poems are very detailed and emotional. They show the influence of "metaphysical poets" like John Donne. However, her biggest influence was the British Romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley. She admired him a lot.

In her first book, Nets to Catch the Wind, her poems had short lines and stanzas. Her images were very clear and polished. Often, her poems showed a feeling of being unhappy with real life. The speaker in her poems often wished for a more beautiful world of art.

A critic named Louis Untermeyer said her first book was brilliant. He noted how she used words to create strong feelings. For example, in "August," you can feel the heat. In "Velvet Shoes," you can almost feel the quiet of snow. Other important poems in this book include "Wild Peaches" and "A Proud Lady."

In Black Armor (1923), her writing became even more passionate and skillful. The poems showed more emotion and cleverness. Critics praised her unique rhymes and perfect rhythm. Poems like "Peregrine" and "Self Portrait" showed her amazing talent.

Trivial Breath (1928) showed a poet who was changing her style. Sometimes her skill was most important, and other times her creative genius shone through.

Elinor Wylie's biographer, Stanley Olson, called the sonnets in her 1929 book, Angels and Earthly Creatures, her best work. These poems were about love, but not just her own private feelings. They explored the many sides of love with strength and emotion. Untermeyer also praised these sonnets. He said other poems in the book, like "Hymn to Earth," were deep and would last a long time.

Her Novels

Elinor Wylie wrote four novels. They are known for being very detailed and full of clever, imaginative ideas.

See also

In Spanish: Elinor Wylie para niños

In Spanish: Elinor Wylie para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |