Eylesbarrow mine facts for kids

The side wall of stamping mill No. 2

|

|

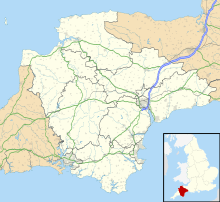

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Dartmoor |

| County | Devon |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 50°29′N 3°58′W / 50.48°N 3.97°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Black tin, kaolin (minor) |

| History | |

| Opened | 1804 |

| Closed | 1852 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Various, see text |

Eylesbarrow mine was an important tin mine located on Dartmoor in Devon, England. It was active in the early 1800s. For a while, it was one of the biggest and most successful tin mines on Dartmoor. The mine was also known by other names, like Eylesburrow or Wheal Ruth. Today, you can still see many of its old buildings and workings near the River Plym. The mine is on the side of a hill called Eylesbarrow, which has two ancient Bronze Age burial mounds (barrows) on top.

Contents

How Eylesbarrow Mine Was Formed

The main rock around the mine is granite. The mining area, called a mining sett, was quite large. It had many lodes, which are cracks in the rock filled with valuable minerals like tin. These lodes usually went straight down and ran from east to north-east.

Most of the mining at Eylesbarrow happened in just three of these lodes. They were not dug very deep. The rock around the lodes was changed by a process called metasomatism. This turned some of the hard granite into a soft mineral called kaolinite, which made it easier for miners to dig.

The tin lodes were up to about 0.73 meters wide. In the early days, the tin ore was very pure and high quality. Miners thought this meant even better ore would be found deeper down. However, it seems the good ore was mostly near the surface. Deeper down, the tin was harder to find.

A Brief History of Tin Mining

People have been mining tin on Dartmoor for many centuries. This includes "tin-streaming," which means collecting tin from riverbeds, and "open-cast mining," which involves digging from the surface. It's thought that tin mining on Dartmoor was busiest around the 1100s. For example, in 1168, people from the nearby village of Sheepstor were known as "tinners." By 1715, almost everyone in Sheepstor Parish was a tinner. However, by then, tin mining on the moor was slowing down because the easy-to-reach tin was running out.

Mining started up again in the late 1700s, thanks to the Industrial Revolution. Some underground mining might have happened at Eylesbarrow as early as 1790. But the first clear record is from 1804, when shares in a mine called "Ailsborough" were offered for sale. Tin payments were recorded from 1806 to 1810.

By 1814, the price of tin was very high. In 1815, actual digging began at the "Ellisborough Tin Set." By 1820, the mine was sending "black tin" (raw tin ore) to Cornwall to be melted down. In 1822, Eylesbarrow mine opened its own smelting house. This was the only one on Dartmoor at the time. They even bought black tin from other mines to melt there.

The next ten years were the mine's most successful. Even though tin prices dropped after 1826, they still sold some "Forest Clay" (which is kaolin). In 1831, over sixty men worked at the mine. But by the end of that year, the smelter closed. There are no records for the next four years.

Why the Mine Closed Down

In 1836, when tin prices were high again, a company called "Dartmoor Consolidated Tin Mines" tried to sell shares. The mine kept working on a small scale, but it wasn't very successful as tin prices fell again. By 1844, with tin prices at their lowest, the mine finally closed.

In 1847, with tin prices rising, the mine was advertised again as "Dartmoor Consols Tin Mining Company." They said the ore was good and the old smelting house could be fixed cheaply.

In June 1847, the mine captain, John Spargo, suggested big improvements. These included a large waterwheel and new crushing machines. Much of this work was done. But by October, there were problems. Not enough shares were sold, and the mine ran out of money. By March 1848, the mine couldn't keep going. No tin had been sold.

Another company, "Aylesborough," was formed in 1848 and sold some black tin. In 1849, Captain Spargo reported that the crushing machines were working well. But problems returned. In 1851, the mine was advertised one last time as "Wheal Ruth." This new company had only a few workers but sold some tin. However, in September 1852, all the mine's equipment was put up for sale. Even though tin prices were rising, it seems the mine simply ran out of tin that was easy to get.

What We Know About the Mine

Even though Eylesbarrow was a big mine, we don't have many maps of its underground tunnels. We also don't have many records of how much tin ore it produced. However, we know that about 276 tons of "white tin" (pure tin metal) were recorded and taxed at Tavistock, the nearest "stannary town" (a town where tin was weighed and taxed). This tin was worth almost £30,000 between 1822 and 1831. The mine's best year was 1825, when it produced over 1,220 hundredweight of tin.

What You Can See Today

Experts from English Heritage surveyed the large mine site in 1999. Their detailed findings are kept in the English Heritage Archive.

Like many valleys on Dartmoor, the area around the upper River Plym shows signs of old "streamworks." There are also "openworks" (open pits) that follow the tin lodes. You can also see traces of "leats" (water channels), reservoirs, and hundreds of "prospecting pits" (small holes dug to find ore). These are all signs of the "old men" who mined tin here centuries before the main Eylesbarrow mine began.

Mine Shafts and Tunnels

You can see 25 shaftheads (the tops of mine shafts) at Eylesbarrow. Most of them are in a curved line along the main tin lode. This line is roughly followed by a track through the mine. The shaftheads look like cone-shaped pits. The smallest is 9 meters wide, and the largest, Pryce Deacon's Shaft, is 16 meters wide. Some, like New Engine Shaft, still have their original stone edges. Each pit has a pile of waste rock, called a spoil heap, nearby. These heaps vary in size; the largest is over 3 meters high. Experts have figured out the names and dates for about half of the visible shafts.

Mine documents mention four "adits," which are horizontal tunnels dug into the hillside to drain water or access ore. Shallow Adit and Deep Adit are from the early 1815 period. Shallow Adit is blocked, but you can see water flowing out of the hillside where it is. Deep Adit is still open. Its entrance is lined with strong granite slabs and is about 2.2 meters high and 0.9 meters wide.

Two Brother's Adit is also open and has a lot of water flowing out of it. This adit is from the later period of the mine, first mentioned in the 1840s. The fourth adit, Deacon's Adit, cannot be found and might have only been planned.

Water Channels, Reservoirs, and Wheel Pits

Even with many underground tunnels, only one waterwheel was used to pump water out of the mine at a time. The first waterwheel, built in 1814–15, had its "wheelpit" (where the wheel sat) just north of the main track. Water for this wheel came from a "leat" (a channel) that carried water from the upper River Plym. In 1818, this leat was extended to collect water from Langcombe Brook as well. Another leat was built in the 1820s to collect water from the northern hillside.

Because the water supply was sometimes not enough, a large reservoir was built before 1825. This reservoir was up to 13 meters wide and 1.3 meters deep. Its 192-meter-long dam was about 10 meters thick and reinforced with large granite blocks. William Crossing wrote that the mine owner, Mr. Deacon, used to take guests boating on the reservoir.

A more powerful waterwheel, suggested by Captain Spargo in 1847, was finished by March 1849. It replaced the older wheel and was placed near the Two Brothers Adit. This waterwheel was huge, 15 meters in diameter, and was likely the biggest on Dartmoor at the time. It used a better water supply, including water from the nearby adit and other leats.

You can still see traces of all these water features today.

The Flatrod System

Mines needed to move power from a waterwheel to pumps or other machines that were far away. In the 1800s, the best way to do this was with a "flatrod system." This system used a series of connected iron or wooden rods. A "crank" on the waterwheel turned its spinning motion into a back-and-forth motion of the rods. These rods were supported and could stretch for a long distance. A heavy weight, called a "balance bob," helped change the horizontal motion of the rods into vertical motion to power pumps down the mine shaft.

At Eylesbarrow, the mine shafts where the water pumps were located were high on the hill. There wasn't enough water there for a waterwheel. So, the power from the waterwheel was carried up the hillside to the shafts using a flatrod system. The rods were made of iron and rested on pulleys. These pulleys ran on short axles supported by pairs of granite pillars. These pillars had special notches cut into their tops to hold the axles. You can still see parts of four lines of these paired pillars today. They vary in height and sometimes run through shallow ditches.

From the first waterwheel's pit, two lines of double pillars go east up the hill. The northern line goes towards Old Engine Shaft, which is 663 meters away. This shaft was used from 1814. The southern line, which is not as well preserved, probably went to Pryce Deacon's Shaft, 777 meters away. This might have been used in the 1840s.

In the second, later wheelpit (shown here), the waterwheel was on the right side of the pit. The flatrod system was on the left. The rods likely traveled underground until they reached a V-shaped ditch.

The flatrods from this wheel went towards Pryce Deacon's Shaft, 961 meters away, and also to Henry's Engine Shaft, 854 meters away. Another branch went to an unnamed shaft to the north, 1192 meters away. We are not completely sure when each of these systems was used, but the extension to the northern shaft was probably part of the very last mining at the site.

Crushing Mills and Smelting House

A "stamping mill" was used to crush the mined ore into fine sand. This sand was then processed on a "dressing floor" to separate the heavier tin ore from the waste rock. The waste was then dumped. There are remains of six stamping mills at Eylesbarrow mine, which is a lot, though they weren't all used at the same time. They form a line down the hillside into the Drizzlecombe valley. They are numbered 1 to 6: No. 1 is the highest, near the first waterwheel; No. 6 is about 0.75 kilometers away and 35 meters lower down. The prominent wall with a hole in it, near the main track, is part of the wheelpit for stamping mill No. 2. The hole shows where the axle was.

The oldest mill is No. 4, which was working in 1804. Mill No. 6 started the next year. It was a large building with its waterwheel in the center. Both these mills were powered by the lower of the two leats from the River Plym. In 1814, three new mills (Nos. 1, 2, and 3) were built, and a higher leat (Engine Leat) was dug to power them.

Mill No. 5, which had the smelter attached, was finished by 1822. The smelting house (shown here today) had two furnaces. One was a "reverberatory furnace" – the large square block in the front was part of this. The other was an older-style "blast furnace," similar to a "blowing house." It had a unique flue (a chimney-like channel) running up the hillside behind it to a short stack. The large standing and fallen granite blocks at the back of the building are what's left of this furnace.

The wheelpit for the waterwheel that powered the blast furnace's bellows was right behind the short standing wall. A small stamping mill and dressing floor were behind that. The three stone pillars in the background might have supported a roof later, after the smelting stopped.

Other Things to See

Some shafts have "balance-bob pits" nearby. You can also see traces of "horse-whims," which were machines powered by horses to lift things in the shafts. Several "reck houses," used for further processing the crushed ore, are also visible. The ruins of the "mansion" or mine captain's house and its other buildings can be seen north of the main track. There are also remains of another mine called Wheal Katherine about a kilometer to the east. These include six shafts, a wheelpit, and another stamping mill (known as No. 7).

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |