First Corps of Cadets (Massachusetts) facts for kids

The First Corps of Cadets of Massachusetts was formed way back in 1741. Its motto is "Monstrat Viam," which means "It Points the Way." Even though it has fought in several wars, the main job of this group was to train officers for new army units. They did this from the American Revolutionary War all the way through World War II.

Contents

History of the Cadets

Starting Out (Early Years)

Unlike other old army groups in Massachusetts, which were made up of all able-bodied men, the First Corps of Cadets was different. It was the oldest volunteer army unit in Massachusetts. It always had young men, and now women, who chose to join and serve.

The idea for the Cadets began in July 1726. A group called the "Company of Young Gentlemen Cadets" welcomed the new governor to Boston. This group had 24 young men. They even bought their own weapons and uniforms! But this group didn't last long.

Benjamin Pollard wanted to create a volunteer army company. It would be for young gentlemen in Boston who had time and money for special duties. In 1741, this company was officially started as the Independent Cadets. Their job was to be the special bodyguards for the royal governors of Massachusetts. On October 16, 1741, Governor William Shirley made Pollard the Captain and Commander. The company was to have "sixty-four young Gentlemen." It officially began on October 19.

Pollard was given a special "dual rank." He was a captain of the Cadets, but also a lieutenant colonel in the regular army. His two lieutenants also had higher ranks. This special privilege came from British Army traditions. Cadet officers kept this dual rank until 1874. Benjamin Pollard was an important person in Boston. He was even the sheriff of Suffolk County. Under his leadership, the Cadets quickly became the best unit in the Massachusetts Militia.

To join, new Cadets had to be chosen by a current member. They also had to buy their own uniform and pay dues. These dues were collected until 1940. Because of these rules, only a few selected people could join.

The Cadets escorted the governor in parades and ceremonies. Once a year, the governor would review the Cadets. This usually happened during the parade for the king's birthday. In 1766, John Hancock joined the Cadets. He is their most famous former member. Hancock later became President of the Continental Congress. He also signed the Declaration of Independence and was governor of Massachusetts.

By 1772, Hancock was the Commander. He helped choose a new uniform. It was a red coat with buff (light brown) parts. This uniform looked like those worn by British Guards. It showed the Cadets' special status. Hancock was one of the richest men in Boston. He could afford new uniforms, drums, and other equipment. Hancock was also a leader in the fight against British taxes. He did not get along with the new royal governor, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Gage. Gage came to Boston in May 1774 to enforce strict rules after the Boston Tea Party.

On August 1, 1774, Governor Gage fired Lieutenant Colonel Hancock from his command. The Cadets usually elected their own officers, so they were very angry. Many Cadets had even been part of the Boston Tea Party. They met on August 15 and decided to break up their company. They returned their flags to the governor to protest. The Cadets gave their uniforms and musical instruments to Hancock for safekeeping.

Because they had disbanded, the Cadets did not fight in the battles of Lexington and Boston in 1775. A few members left Boston to join the American forces. But most former Cadets could not join until the British left Boston in March 1776. In the late spring or early summer of 1776, the Cadets reformed. They called themselves the Independent Company of Cadets again. Red uniforms were no longer suitable, so they chose a black coat with red parts.

Their first parade was on Boston Common on September 9. Hancock, who was now President of the Continental Congress, was made honorary colonel. Henry Jackson was elected captain. The company had 78 members. The Cadets wanted to fight in the Revolutionary War. They asked the government for permission to create a battalion for the Continental Army. Soon after, Captain Jackson was made a colonel. He became commander of Jackson's Additional Continental Regiment on January 12, 1777.

The Cadets provided the officers for this new regiment. It was formed in the spring of 1777. Jackson's Regiment fought at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778. It also took part in campaigns in New Jersey and Rhode Island. The regiment was disbanded near West Point, New York, on December 31, 1780. Because the Cadets were always made up of young men who could be officers, they started a tradition. Their second main job was to provide officers for wartime regiments. This began in 1777 and continued through World War II (1941–1945).

In the 1920s, the War Department gave the Corps three special flags (campaign streamers). These were for battles won by Jackson's Regiment. In 1976, the Army gave them two more Revolutionary War streamers.

While many members were serving in the army, the Cadets themselves were called to active duty in April 1777. They marched to Rhode Island. The Cadets served again in the spring of 1778. They were a guard unit at Dorchester Heights. The Cadets also served under their former commander, Major General Hancock, in July and August 1778. Hancock led the Massachusetts Militia in a short fight against the British in Rhode Island. Jackson's Regiment, formed by the Cadets, also fought in this campaign. After their third active duty, the Cadets were inactive until 1785. In August 1786, the Cadets reorganized with 36 members. They adopted a white uniform. This honored a French Army regiment they served with in Rhode Island in 1778.

On October 19, 1786, the Cadets were officially reorganized. They were given special privileges by the Massachusetts government. The Cadets continued to be the governor's official bodyguards. They were to be part of a larger headquarters unit. They would also be commanded by a lieutenant colonel. These special privileges were recognized by the US government. On their reorganization parade on October 19, Governor James Bowdoin gave the Cadets new flags. The flags had a sunburst star and the motto "Monstrat Viam." The sunburst star was like the symbol of the Coldstream Guards of the British Army. This symbol and motto are still used by the Cadets today.

Days after reorganizing, the Cadets were called to state service during Shays' Rebellion. The Cadets marched to Groton to help the sheriff enforce state law.

Because the Cadets were first organized on October 19, 1741, and reorganized on October 19, 1786, this day became special. For many years, officers received their commissions on October 19. The Cadets attracted young Boston gentlemen with time and money. They drilled regularly and participated in parades. But the social side of the Cadets was just as important.

Throughout their history, the Cadets have provided honor guards for important visitors to Boston. In October 1789, the Cadets escorted President George Washington during his first visit to Boston. They also escorted President Washington again in 1793 and President John Adams in 1797.

Quasi-War with France and Beyond

During the "Quasi-War" with France in 1797, the Cadets offered to serve in the Volunteer Army. The old "standing militia" (where all men had to serve) was becoming less effective. Volunteer militia units, like the Cadets, took their place. These units had uniforms, equipment, and drilled regularly. In 1840, Massachusetts replaced the standing militia with volunteer regiments. From 1842 to 1844, Colonel William P. Winchester led the Cadets.

In the early 1800s, many volunteer units formed in Boston. The National Lancers, started in 1836, became the governor's mounted bodyguards. Other elite units like the Boston Fusiliers also formed. The Cadets began a friendly competition with these groups. In 1786, the Second Corps of Cadets of Salem was formed. Both the First and Second Corps of Cadets had special privileges.

The time between 1815 and 1860 was the best period for volunteer militias. Every town had several companies. They proudly paraded in their often fancy uniforms. The Cadets often changed their uniforms to be the most splendid in Boston. Between 1810 and 1860, their uniform changed many times. Because new uniforms were expensive, only wealthy young men could afford to join.

The Cadets also changed their name often. Between 1801 and 1861, they used names like Boston Independent Cadets and Independent Company of Cadets.

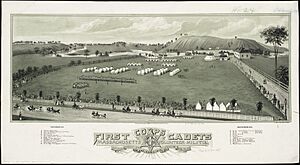

The Cadets, like other volunteer units, started attending summer training sessions. These lasted several days. The Cadets also celebrated their organization day with a parade on Boston Common. They also paraded on Independence Day and other holidays. The Cadets often escorted the governor to Harvard University graduations. This was fitting because many Harvard graduates were in the Cadets. Since the Cadets were an infantry company, a state law in February 1861 limited their size to 100 members.

The Civil War (1861-1865)

When the Civil War started in April 1861, the Cadets changed their focus. They stopped worrying about uniforms and parades and prepared for war. The Cadets volunteered for state service in May. They were assigned to guard the state house and state arsenal. Massachusetts provided five regiments for the war. But because the Cadets were an independent company, they were not assigned to a regiment.

The Cadets were always made up of well-educated young men. They lived up to their name by providing officers for the new volunteer regiments. Just as they had provided officers for Jackson's Regiment in 1777, in 1861 they supplied officers for the 2nd, 20th, and 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments. About 170 Cadets became officers. Five of them even reached the rank of brigadier general.

The Cadets provided most of the officers for the 2nd Massachusetts, formed in May 1861. Cadets George Gordon and George Andrews, both West Point graduates, became colonel and lieutenant colonel of the 2nd. The 2nd was called "the best officered regiment in the entire Army." Every officer was carefully chosen.

The year 1862 was very busy for the Corps. On May 26, the Corps entered federal service for the first time. The Cadets went to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. There, they guarded Confederate prisoners. The Cadets still wore their grey peacetime uniform. While in federal service, they were given the standard blue army uniform. The Corps was released from federal service on July 2, 1862.

President Lincoln asked states to provide militia regiments for nine months of service. The Corps was given the job of organizing the 45th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The Corps provided most of the officers and non-commissioned officers for the 45th. The "Cadet Regiment," as the 45th was known, joined federal service on September 26, 1862. Its mission was to help the Union forces occupying the North Carolina coast.

The 45th arrived in North Carolina in early November. It camped near Newbern. The regiment fought at Kinston on December 14 and at Goldsboro two days later. The 45th also took part in smaller actions in April 1863. When its service term ended, the 45th left service on July 8. For its service in the 45th, the Corps received two campaign streamers. These were for North Carolina 1862 and North Carolina 1863. They are now displayed on the Corps' flags.

However, the 45th's service was not completely over. Its commander was ordered to reorganize the regiment for state service on July 14. This was to restore order in Boston during the draft riots. The 45th quickly brought order to the streets of Boston.

While most of its members were with the 45th, the Corps remained in state service as a home guard unit. The Corps had two jobs during the Civil War. It provided officers for new units. Older Cadets stayed in Boston for state service. This happened in July 1863. The Cadets wore blue uniforms, as grey was not suitable. They were ordered to guard the governor and the state capitol during the draft riots. Their "offspring," the 45th Regiment, was serving nearby at Faneuil Hall.

After the Civil War

After the Civil War, people were less interested in military matters. Many volunteer militia units disappeared. But the Corps continued, though its membership dropped to 60. However, the Corps began to grow again. A new dress uniform was adopted in 1868. It had a white tunic, sky-blue trousers, and a black shako (a tall, stiff hat). White was the traditional color for dress uniforms. Sky-blue was the traditional color for infantry. This uniform is still the official Corps dress uniform. It was made simple to keep costs down for new members. While earlier uniforms were influenced by British and French styles, this one was based on Austrian Army uniforms.

The Corps started recruiting to get back to full strength. Since the cost of joining had been high before, with reasonable uniform and dues costs, the Corps began attracting young businessmen. In November 1872, the Corps helped police the city after a terrible fire. In July 1873, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas F. Edmands was elected to command the Corps. Edmands led the Corps for 33 years. Under his leadership, the Corps became strong again. It was once more the top militia unit in Massachusetts. As a Civil War veteran, he knew the Corps had to be a skilled infantry unit. The Corps was both a well-drilled parade unit and an infantry battalion ready for field service.

In 1874, the Cadets were finally named the First Corps of Cadets. They expanded into a battalion. The special privilege of dual rank ended. Officers now held their higher rank with the battalion organization.

The Veteran Association of the First Corps of Cadets was formed in 1876. Its goal was to raise money for a new armory (a building for military training and storage). Over the years, this association has helped keep the Corps' history and traditions alive. As Boston's elite militia unit, the Corps needed a suitable armory. In the late 1800s, there was a trend to build large, fortress-like armories for the National Guard. These buildings showed that the National Guard was ready to keep civil peace. National Guard units raised the money to build these large and often fancy armories.

In 1878, the Corps began raising money for its armory. The Corps raised half the money needed through public donations. The rest of the money came from operettas (short operas) sponsored by the Corps. These were very popular in Boston. The armory's first stone was laid in 1891. Construction finished in 1897. The Armory of the First Corps of Cadets is an impressive building in Boston. It was named a Boston Landmark in 1977. During the Spanish–American War in 1898, the Corps was not called for federal service. Only full infantry regiments were needed. Instead, the Corps guarded coastal artillery bases.

World War I (1914-1918)

With changes to the National Guard starting in 1903, the Corps focused on infantry training. But they also continued their social activities and parades. The Corps performed state duty after the Chelsea fire in 1906 and the Salem fire in 1914. In 1912, the Corps served for several weeks during a textile workers' strike in Lawrence. The Corps even bought their own machine guns and cars. This was an early experiment as motorized infantry.

The Corps realized it could not continue as a separate infantry battalion. It was not a standard unit type. So, the Corps was not called for service on the Mexican border in 1916. The 275-man unit played no role in that crisis. In the winter of 1916-1917, the Corps discussed its future. They were told there were no plans to include them in the new 26th Division being formed for war. In early 1916, the Corps continued training potential officers. They sponsored classes for enlisted men and civilians. These people later attended training at Plattsburgh Barracks, New York.

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, the Corps decided to become engineers. They were allowed to form the engineer regiment for the 26th Division. On May 22, they were renamed the 1st Regiment of Engineers (First Corps of Cadets), Massachusetts National Guard. The Corps reorganized as a regiment. Many of its members became the officers and non-commissioned officers of the new group. They immediately started recruiting to reach their full strength of 1,634 members. The 1st Engineers joined federal service on June 20, 1917. They began training in the Armory and at Wentworth Institute.

With the entire Massachusetts National Guard in federal service, the state needed a home guard. The Veteran Association organized the First Motor Corps. This was its contribution to the Massachusetts State Guard. The First Motor Corps was accepted for state service on June 5, 1917.

Meanwhile, the Corps, as a new engineer regiment, trained hard. To reach full strength, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry transferred 82 men. The 1st Maine Field Artillery transferred 100 men. Also, 479 Coast Artillery men from the Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island National Guards joined.

On August 18, the Corps was officially renamed the 101st Engineers, 26th Division. On September 15, on the Common, the entire regiment paraded for the first time. They were given new flags.

The 26th was the first National Guard division and the second US Army division to go overseas in World War I. The 101st Engineers arrived in France in October. The first group landed on the 19th, which was the Corps' 176th anniversary. Engineer troops were in short supply. The Corps immediately started building barracks and hospitals. The Corps went to the front lines in February 1918. They were in the Chemin des Dames area in France. They helped the 26th Division by rebuilding trenches, dugouts, and roads. The Corps also had its first casualties (soldiers killed or wounded) of the Great War.

In late March 1918, the 101st moved to the Toul area in Lorraine. They supported the 26th by building concrete shelters (pillboxes), strong points, digging trenches, and rebuilding roads. In July, the 101st moved to Château Thierry. They worked despite heavy shelling. For several days, the 2nd Battalion, 101st Engineers, fought as infantry. In September, the Corps moved to Saint-Mihiel. They worked non-stop rebuilding roads for artillery movement. When the armistice (peace agreement) was signed on November 11, the Corps was still working hard.

The 101st Engineers returned to Boston on April 5, 1919. While getting ready to leave the army at Camp Devens, they took part in the 26th Division's farewell parade on April 25. Four days later, the 101st was disbanded and released from federal service. Four Cadets received the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation's second-highest award. The 101st was awarded six campaign streamers for its service in World War I.

While the First Corps of Cadets was reorganizing, its sister unit, the First Motor Corps, was called to active state service in September 1919. They acted as police during the Boston Police Strike. The First Motor Corps was released on December 6 and disbanded.

Between the Wars

The First Corps of Cadets was reorganized on July 27, 1921. It was called the 1st Separate Infantry Battalion. This was a temporary name. With this change, the Corps was no longer part of the 26th "Yankee" Division. In March 1922, the Corps became the 211th Machinegun Battalion, Coast Artillery Corps. But in May 1923, it was reorganized again. It became the 2nd Battalion, 211th Artillery, Coast Artillery Corps. It was officially recognized by the federal government in April 1924.

Other Names for the Cadets

- 1741 - Governor's Company of Cadets (Provincial)

- 1776 - Independent Company (during Revolution)

- 1786 - Independent Company of Cadets

- 1799 - Independent Corps of Cadets

- 1803 - Independent Cadets

- 1840 - Divisionary Corps of Independent Cadets

- 1854 - Independent Company of Cadets

- 1861 - Independent Corps of Cadets

- 1866 - First Company of Cadets

- 1874 - First Corps of Cadets

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |