Francisco Ferrer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francisco Ferrer

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | January 14, 1859 Alella, province of Barcelona, Spain

|

| Died | October 13, 1909 (aged 50) Barcelona, province of Barcelona, Spain

|

| Known for | Escola Moderna |

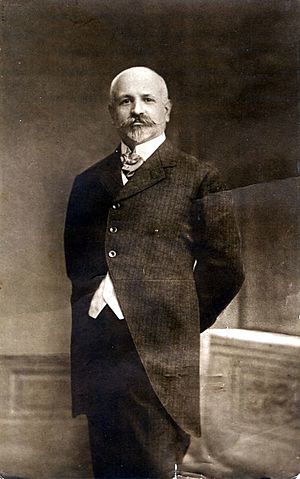

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia (born January 14, 1859 – died October 13, 1909), also known as Francisco Ferrer, was a Spanish thinker and educator. He believed in free thinking and anarchism, which is a belief in self-governing communities without a strong central government. He started a group of private, non-religious schools in and around Barcelona. These schools were called libertarian schools, meaning they focused on freedom and individual growth.

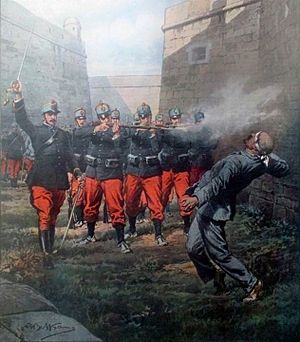

Ferrer was put to death after a period of unrest in Barcelona. His death made him a hero to many people around the world. This led to an international movement where people started schools based on his ideas and teaching style.

Ferrer grew up on a farm near Barcelona. From a young age, he believed in republicanism, which means he thought people should have a say in their government. He also questioned the power of the church. As a train conductor, he secretly carried messages for a republican leader who was living in France. After some political trouble in Spain in 1885, Ferrer and his family moved to Paris, France, where they lived for 16 years.

In Paris, Ferrer became very interested in anarchism and new ways of teaching. Around 1900, he decided to open a special school. He got a large amount of money from a student he tutored in Paris, which helped him make his dream a reality.

When he returned to Barcelona in 1901, Ferrer opened the Barcelona Modern School, called Escuela Moderna. This school offered a non-religious and freedom-focused education. It was a different choice from the strict religious teaching and required lessons common in Spanish schools at the time. Ferrer believed that children should have lots of freedom and not be forced to conform. His school did not use punishments, rewards, or exams. Instead, it encouraged learning through real-life experiences rather than just studying books. The school also offered classes for adults, trained teachers, and had a printing press that made textbooks and a school newspaper. About 120 similar schools opened across Spain.

The quick growth of Ferrer's ideas worried the Spanish church and government. They saw his school as a place that encouraged rebellion. Ferrer was linked to a 1906 attempt to harm the Spanish King. This was used as an excuse to close his school. However, he was later released without being found guilty, thanks to pressure from other countries. Ferrer then traveled around Europe, speaking about the need for change in Spain. He also started a group to support libertarian education and reopened his printing press.

In 1909, Ferrer was arrested and accused of planning a week of protests and unrest in Barcelona, known as the Tragic Week. Even though Ferrer was likely involved in some way, he probably didn't plan the whole event as he was accused. His trial was very unfair, and he was put to death. This caused a huge outcry around the world, as many people believed Ferrer was innocent. He was honored with writings, monuments, and protests in many countries. The protests grew into a movement to spread his educational ideas, and Modern Schools named after him appeared across the United States and Europe, and even in Brazil and Asia.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia was born on January 14, 1859, on a farm near Barcelona in Alella, Spain. From a young age, he became a republican and a free thinker. His parents were religious, but his uncle, who was a free thinker, and his first boss, who didn't believe in God, helped him form his own independent ideas and question the church.

In his mid-20s, Ferrer became a strong supporter of republican ideas. In 1883, he joined a Masonic Lodge in Barcelona, a type of social and charitable group. He used his job as a train conductor between France and Barcelona to help a republican leader who was living in exile. He also helped other republicans and free thinkers find safety.

After supporting an attempt to create a Spanish Republic in 1886, Ferrer had to escape to France with his wife and three daughters. They stayed there for 16 years. While in France, Ferrer continued his activities with the Masonic group.

Life in Paris

In Paris, Ferrer taught Spanish and worked as a secretary for the republican leader until 1895. He also got involved in other social movements. He supported Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer who was wrongly accused of treason. Ferrer also taught at a Masonic school.

After the republican leader's death, Ferrer started to learn more about anarchism. He met many important anarchist thinkers and became friends with them. Even though Ferrer later denied being an anarchist, especially when the government was watching him closely, many historians agree that he was. Throughout his life, Ferrer supported anarchist causes, helped fund their work, and published anarchist books. Many anarchists from Barcelona worked with the school Ferrer later opened, and important anarchist leaders in Europe advised him and wrote for his publications.

While in Paris, Ferrer became very interested in education. This was a popular topic among anarchists and rationalists, who believed in reason and science. Ferrer was very impressed by a school run by Paul Robin, which aimed to develop children's minds and bodies without force. Robin believed that a child's environment was more important than their genes. His school focused on nature, exercise, love, and understanding, especially for children who were often looked down upon.

Around 1900, Ferrer decided to open a similar school. This became possible when he inherited about a million francs (a large sum of money) from a French woman he had tutored in Spanish. She believed in his ideas.

Barcelona Modern School

With the money he inherited, Ferrer returned to Spain in 1901. He founded the Barcelona Modern School, Escuela Moderna. At this time, Spain was thinking a lot about its future after losing the Spanish–American War. Many people wanted schools to be less religious and teach more science, history, and sociology. Ferrer, who did not believe in God, became a key voice in these discussions. He wanted a school based on reason, as an alternative to the religious and strict lessons common in Spanish schools. He was not a flashy speaker, but his honesty and organizing skills inspired others.

Ferrer's teaching style was based on ideas from the 18th and 19th centuries. It focused on giving children lots of freedom instead of making them conform to strict rules. It combined play and crafts with schoolwork. It also promoted reason, dignity, self-reliance, and scientific observation over blind obedience. The school encouraged learning through experience rather than just memorizing facts. Children were treated with love and kindness. Ferrer believed that changes in education could help people think more freely and challenge the old ways that the church and state supported. For Ferrer, free education meant teachers would help children want to learn on their own, rather than forcing ideas on them.

The Escuela Moderna opened in Barcelona in September 1901 with thirty students. Five years later, in 1906, it had more than 126 students before the government closed it. The school charged different fees based on what parents could afford. Ferrer's teaching aimed to remove strict rules from education and help children develop their own abilities. The school did not use punishments or rewards, as Ferrer felt these encouraged dishonesty. He also didn't use grades or exams, believing they could harm a child's self-esteem. Ferrer focused on practical knowledge over theory. Lessons often involved trips to factories, museums, and parks so children could experience what they were learning firsthand. Students planned their own work and were trusted to attend as they wished.

The Escuela Moderna also had a school to train teachers and a printing press. This press translated and created over 40 textbooks for Ferrer's school. These books were written in easy-to-understand language about new scientific ideas. The Spanish authorities disliked these books because they covered topics from math and grammar to science and social studies, and even questioned patriotism. The school's monthly newspaper shared news and articles from important thinkers who believed in freedom.

Besides helping children develop, Ferrer believed the school had another important purpose: to help create a better society. He saw the school as a small version of the free society he hoped to see in the future. Teaching about social change was a key part of the Escuela Moderna's goals. Ferrer dreamed of a society where people were always learning and improving themselves and their surroundings. To do this, students were taught about social justice, equality, and liberty. They learned that capitalism was unfair, government could be like slavery, and war was a terrible crime. Their textbooks spoke out against capitalism, the state, and the military. This education was also for adults. Parents were invited to help run the school, and the public could attend evening and Sunday classes.

Ferrer was a central figure in Barcelona's education movement for ten years. His school's program, from its anti-church views to its guest speakers, impressed even some middle-class reformers. Many people believed Ferrer's careful organizing skills helped the school grow.

Other schools and centers based on his model spread across Spain and even to South America. By 1905, there were 14 Ferrer schools in Barcelona and 34 across other regions of Spain. Spanish republicans and other free-thinking groups also used materials from Ferrer's press to organize their own classes, with about 120 such schools in total.

Political Challenges

The quick rise of Ferrer's influence worried the Spanish authorities. His money and organizing skills made his efforts to challenge the system even stronger. Authorities saw his school as a place that encouraged rebellion. Ferrer's ideas were seen as a danger to many traditional parts of society, like the church, the government, the military, and the family.

In the early years of the school, Ferrer supported ideas of anarcho-syndicalism, which is a belief in workers owning and controlling their workplaces. He published a newspaper about this idea and worked to organize workers in Catalonia. In April 1906, Ferrer led a parade of 1,700 children to support non-religious education.

Ferrer faced threats and unfair criticism for his work in Barcelona. Police searched his house and followed him. There were also false rumors spread about him to damage his reputation.

In 1905, Ferrer and the Modern School spoke out against bullfighting.

Ferrer was accused of being involved in a 1906 plot against Spanish King Alfonso XIII. The person who tried to harm the King worked at Ferrer's school press. Although the attempt failed, it was used as an excuse to arrest Ferrer. He was arrested in June 1906 and accused of planning the attack. Within two weeks, the government closed his school because of its connection to the incident. Ferrer waited a year for his trial, where he was found not guilty because there wasn't enough proof.

Ferrer's exact role in this event is still unclear. He was a strong believer in direct action and sometimes thought violence could be useful. Some historians suggest Ferrer might have helped with the plot, but the official records from that time were often biased and not strong enough to prove his guilt.

After the Escola Moderna

Ferrer was released from prison in June 1907. Many groups around the world, who believed in anarchism and rational thinking, supported him. They saw his case as another example of unfair treatment in Spain. The next month, Ferrer traveled around Europe, speaking about the need for change in Spain. When he returned to Barcelona in September, he was not allowed to reopen his school. However, he reopened his printing press, where he published new textbooks and translations. He also helped create a workers' union and its newspaper.

In April 1908, Ferrer founded the International League for the Rational Education of Children. This group aimed to promote libertarian education across Europe. Its main newspaper included articles by important anarchists and educators. In its first year, the League helped start libertarian schools in other cities like Amsterdam, Brussels, and Milan.

Ferrer was arrested again in August 1909 after a week of protests and unrest in Barcelona, known as Tragic Week. Citizens were upset about a war and government corruption. They protested against sending more soldiers to fight in Morocco. A general strike led to a week of riots, which caused many deaths and arrests. Ferrer was accused of planning the rebellion and became its most famous victim.

Even though Ferrer was involved in the events of the Tragic Week, he did not plan the whole thing as he was accused. Many reliable accounts say the unrest happened spontaneously, not because of a planned anarchist plot. Ferrer likely participated, but his role was probably small. The evidence used in Ferrer's military trial included statements from his political enemies and his past writings, but no real proof that he planned the rebellion. Ferrer said he was innocent and was not allowed to present his own witnesses.

The court case that led to Ferrer's death was decided very quickly. Many historians later called it an "unfair killing." They believed it was an attempt to silence a person whose ideas were seen as dangerous to the existing system, especially since he had not been found guilty in the earlier plot against the King. His last words on October 13, 1909, were, "Aim well, my friends. You are not responsible. I am innocent. Long live the Modern School!"

Legacy

Ferrer's execution became known as a "martyrdom" for the causes of free thought and rational education. Many people believed Ferrer was innocent when he died. His death caused protests and anger around the world. Not just anarchists, but many liberals saw Ferrer as a hero who was unfairly treated by a vengeful church and a traditional government. Protests happened in major cities across Europe, and hundreds of meetings took place in America, Europe, and Asia. A crowd of 15,000 people went to Paris's Spanish embassy, and a black flag, a symbol of anarchism, was hung from the Milan Cathedral. Famous British writers spoke out in anger. Ferrer's death was widely covered, even on the front page of The New York Times.

The worldwide protests turned into the Ferrer educational movement, honoring him. His execution made Ferrer the most famous libertarian educator. His writings were translated into many languages, and a movement for rational education spread globally. Modern Schools named after him appeared across Europe and the United States, including a long-lasting community in Stelton, New Jersey. Schools named after him reached as far as Argentina, Brazil, China, Japan, Mexico, Poland, and Yugoslavia.

Groups built public memorials and named places after Ferrer across Europe. Brussels put up a marble memorial for Ferrer in its main square in 1910. In 1911, it also put up Ferrer's first statue, showing a man holding a torch of enlightenment. This statue was destroyed in 1915 during World War I but was rebuilt in 1926 by the international free thought movement. Public places in France and Italy were also named after Ferrer.

The international outrage over Ferrer's execution led to the downfall of the Spanish government at the time.

See also

In Spanish: Francisco Ferrer Guardia para niños

In Spanish: Francisco Ferrer Guardia para niños

Images for kids