Freels Farm Mounds facts for kids

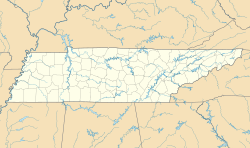

| Location | Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Anderson County, Tennessee, |

|---|---|

| Region | Anderson County, Tennessee |

| Coordinates | 35°58′24″N 84°13′06″W / 35.97333°N 84.21833°W |

| History | |

| Cultures | Late Woodland Culture |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1934 |

| Archaeologists | William S. Webb, T.M.N. Lewis, A.P. Taylor |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | burial mound |

| Responsible body: Tennessee Valley Authority, Civil Works Administration, Federal Relief Administration | |

The Freel Farm Mound Site (also called 40AN22) is an ancient burial mound in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It's an important archaeological site from the Woodland cultural period. Today, the site is underwater, covered by Melton Hill Lake.

In 1934, archaeologists dug up the mound. This was part of a big project called the Norris Basin Survey. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) led the work. They used workers from the Civil Works Administration. During the dig, they found 17 burials and some ancient tools. These finds are now kept at the McClung Museum in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Contents

What the Mound Looked Like

The Freel Farm Mound is located on land owned by the U.S. Department of Energy. Before it was covered by water, the mound was on the William Freel farm. It was about two miles southeast of Scarboro, Tennessee. The mound sat on a wooded hill, not far from the Clinch River.

The Freel family had owned the land for over 135 years. They farmed the fields around the mound, but they never disturbed the mound itself. When archaeologists found it, the mound was covered with plants. Eight large trees were even growing on it. The roots from these trees had grown deep into the mound. A small part of the mound on the west side had been removed to make a dirt road.

The mound was round, like a circle. It was about 40 feet wide and 8 feet tall. It was made of hard, yellow clay with tiny bits of charcoal mixed in. Near the center, there was a special grave dug below the ground. This grave held "Burial No. 17," which was covered by large stones.

The stones were stacked in a circle, about 16 feet wide. This stone circle and Burial No. 17 were the first parts of the mound. More earth was added on top of the stones as other bodies were buried there over time.

Experts believe the mound was built during the Late Woodland period. This was likely between 500 and 1000 CE. The way people were buried in the mound tells us about their society. It suggests that not everyone was treated the same way after death.

Why the Site Was Dug Up

The Freel Farm Mound was excavated in 1934. This happened because it was near the area where the Norris Dam was being built. In the 1930s, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) started a big archaeological survey. They wanted to find and dig up all ancient sites in the Norris basin. Their goals were to find all prehistoric sites, dig them up, and save all important information and artifacts.

The survey found 23 important prehistoric sites. The Freel Farm Mound was the 22nd site they found. Even though this mound was downstream from Norris Dam and wouldn't be flooded by it, it was still dug up because it was so close to the project area.

The TVA worked with the Civil Works Administration and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. They hired T.M.N. Lewis to lead the archaeological survey. Lewis was in charge of the site's excavation. A.P. Taylor was the supervisor working directly at the site.

Later, in the 1960s, the Melton Hill Dam was built south of Oak Ridge. This dam caused the water levels in the Clinch River to rise permanently. As a result, the Freel Farm Mound became completely covered by water.

Digging Up the Mound

Archaeologists divided the mound into 5-foot squares. They used stakes to mark these squares. They looked for different layers of soil, but they didn't find any clear ones. This meant the mound was built all at once, not in many different stages. They were very careful to keep the sides of their trenches clean and straight as they dug down.

The dig didn't find any signs of a living area, like old trash piles. They also didn't find any broken pottery in the mound. There was no evidence of any buildings at the site. This means archaeologists learned very little about who built the mound. The most important discoveries were the burials and the stacked stone circle. They also figured out that the yellow clay covering the mound was clean. It was brought in from somewhere else to cover the bodies.

Burials Discovered

Archaeologists found 17 burials inside the mound. They numbered them in the order they were found.

- Burial No. 1: An adult buried with their knees bent. A piece of drilled conch shell was found near the neck.

- Burial No. 2: An adult found on the ground floor, partly bent.

- Burial No. 3: Another adult on the ground floor, partly bent, but not well preserved.

- Burial No. 4: A partly bent skeleton found about 11 inches below the mound's surface. It was not well preserved.

- Burial No. 5: Bones found on the ground surface that were very decayed.

- Burial No. 6 and Burial No. 7: Parts of three bodies: two adults and one child. Tree roots had damaged the bones.

- Burial No. 8: A skull piece and lower leg bones of an adult, found 22 inches above the ground floor.

- Burial No. 9: A nearly fallen apart adult found just below the mound surface. A flint spear point was also found.

- Burial No. 10: A crushed skull found 10 inches above the ground floor, under a tree.

- Burial No. 11: A skull, collarbone, and rib of an adult, found 20 inches above the ground floor.

- Burial No. 12: An adult found 18 inches above the ground floor, not well preserved.

- Burial No. 13: A "bundle burial," meaning the bones were gathered together, not in their natural body position.

- Burial No. 14: An adult found 15 inches above the ground floor, partly disturbed. Some bones were not in their natural order. A rock was placed over the leg bones.

- Burial No. 15: Another bundle burial.

- Burial No. 16: A crushed skull found on the ground floor, near a shell bead with a hole in it.

- Burial No. 17: This was the best-preserved skeleton and the first one placed in the mound. It was the only one in good enough shape to be studied by W.D. Funkhouser, an expert from the University of Kentucky. He compared its measurements to other skeletons found in the Norris Basin Survey.

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |