G factor (psychometrics) facts for kids

The g factor (also known as general intelligence or general mental ability) is a concept in psychology that helps us understand human intelligence. Imagine you're good at one school subject, like math. The g factor suggests you'll probably be good at other subjects too, like reading or science. This is because there seems to be a common "brain power" that helps with all kinds of mental tasks.

This idea was first suggested by a British psychologist named Charles Spearman over 100 years ago. He noticed that students who did well in one subject often did well in others. He thought this was because of an underlying general mental ability, which he called g. Today, scientists often think of intelligence like a pyramid: many specific skills at the bottom, a few broader skills in the middle, and at the very top, the g factor, which connects all of them.

Scientists agree that the g factor is a real pattern seen in data from people all over the world. However, they are still trying to figure out exactly why different mental tasks are connected in this way.

Contents

- How We Measure Brain Power

- Ideas About What g Is

- How Our Brain Abilities Are Structured

- Is g Always the Same?

- How g Changes with Age and Ability

- Why g Matters in Real Life

- Genes and Environment's Role

- Brain Science and g

- g in Animals

- Similarities and Differences Among Groups

- How g Connects to Other Brain Ideas

- Criticisms of g

- Images for kids

- See also

How We Measure Brain Power

Cognitive ability tests are designed to measure different parts of your thinking skills. These tests can look at things like your math skills, how well you use words, how you understand shapes and spaces, and your memory.

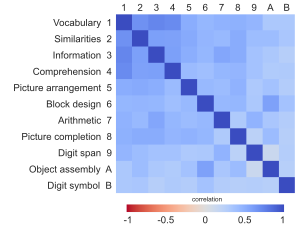

But here's something interesting: people who do well on one type of test often do well on others. And those who struggle with one test tend to struggle with others, no matter what the test is about. Charles Spearman was the first to notice this pattern in 1904. He saw that children's scores in different school subjects were all connected. This idea, that all mental test results are positively connected, is one of the most proven ideas in psychology.

Using special math tools, scientists can find a single common factor that links all these different tests. Spearman called this the general factor, or simply g. (It's always written as a small, italic 'g'.) This g factor helps explain why people's scores on different tests vary. It's not about how much g a single person has, but how their g compares to others.

Different tests are connected to the g factor in different ways. This connection is called a g loading. A test with a high g loading means it measures a lot of that general brain power. For example, tests like Raven's Progressive Matrices, which involve solving puzzles with patterns, often have very high g loadings. Vocabulary and general knowledge tests also tend to have high g loadings.

Tests that are more complex and require more thinking usually have higher g loadings. For instance, repeating numbers backward is harder than repeating them forward, and it has a higher g loading. Solving a math problem is more complex than just doing a simple calculation, and it also has a higher g loading.

It's important to remember that how hard a test is (its difficulty) is not the same as its g loading. Some tests might be hard but don't measure as much g as other tests that involve more reasoning.

Ideas About What g Is

While most experts agree that g exists as a statistical pattern, they don't all agree on what causes it. Here are some of the main ideas:

Mental Energy or Efficiency

Charles Spearman thought that g was like a "mental energy" that helps us with all kinds of thinking tasks. He believed that the best ways to see g were in tasks that involved figuring out relationships, solving problems, and finding patterns. He hoped that future research would discover the physical basis of this mental energy in the brain.

Later, another researcher named Arthur Jensen suggested that g might be related to how fast or efficient our brain processes information. He thought that people with higher g might have brains that work more quickly or smoothly.

Sampling Theory

Some scientists, like Edward Thorndike and Godfrey Thomson, suggested a different idea. They thought that our brains have many different, separate mental processes. When you take a test, it uses a "sample" of these processes. The reason tests seem connected (the "positive manifold") is because different tests might use some of the same mental processes. So, it's not one big g factor, but rather the overlap of many smaller, separate abilities.

This idea suggests that more complex tasks have higher g loadings because they use a larger sample of these mental processes, meaning they overlap more with other tasks. However, critics point out that some very different tests (like vocabulary and pattern puzzles) are highly connected, while some similar ones (like repeating numbers forward vs. backward) are less connected. This doesn't fit perfectly with the sampling theory.

Mutualism Model

The "mutualism" idea suggests that our cognitive processes (like memory, reasoning, and language) start out separate. But as we grow and learn, these processes help each other. For example, if you get really good at reading, it might help you learn new things faster, which then helps your reasoning skills. Over time, this "mutual benefit" makes all your cognitive abilities become connected, even if they weren't at first. This means there isn't one single thing causing the connections, but rather a network of abilities helping each other grow.

How Our Brain Abilities Are Structured

Scientists use a math technique called Factor analysis to understand how different intelligence tests are connected. This helps them simplify the many connections into a smaller number of main ideas, or "factors." When all tests are positively connected, factor analysis often points to a general factor, which is the g factor. This g factor usually explains about 40% to 50% of the differences in scores on IQ tests.

Charles Spearman created factor analysis to study these connections. His first idea was that all intelligence test scores could be explained by two things: specific skills for each test, and the g factor that connects them all. This was called Spearman's two-factor theory.

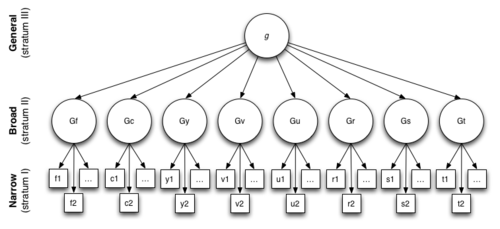

Later, with more diverse tests, scientists found that g alone couldn't explain everything. They realized that even after accounting for g, some tests were still connected. This led to the idea of "group factors." These are broader skills like verbal ability, spatial ability, or numerical ability, which are shared by groups of similar tests, in addition to the overall g.

Today, most experts agree that our cognitive abilities can be seen at three levels:

- Lowest level: Many specific, narrow skills (like knowing a specific fact).

- Middle level: A smaller number of broader skills (like fluid intelligence or crystallized intelligence).

- Top level: The single g factor, which is the general ability common to all tests.

The g factor is usually the most important factor, explaining most of the common differences in IQ test scores. Modern models of intelligence, like the three stratum theory, include all these levels.

Is g Always the Same?

Spearman believed that the exact content of an intelligence test didn't matter much for finding g, because g is involved in all mental tasks. So, any good test could be an indicator of g. Arthur Jensen later agreed, saying that a g factor found from one set of tests would be pretty much the same as one found from another large, varied set of tests. This means that if you combine scores from many different tests, the g part of those scores adds up, while the unique parts of each test cancel out.

However, some researchers, like L. L. Thurstone, argued that a g factor might change depending on the specific tests used. They thought it just reflected the average of the abilities in that particular set of tests.

Recent studies have tried to answer this. Researchers gave the same people several different sets of intelligence tests and then looked at the g factors from each set. In one study, the g factors from three different test sets were almost identical. Another study found similar results, suggesting that the same g can be found consistently, as long as the test sets are varied enough.

How g Changes with Age and Ability

Some scientists have suggested that the importance of g might not be the same for everyone. Spearman's law of diminishing returns (SLODR) predicts that the connections between different cognitive abilities are weaker in people who are more intelligent. This means that for very smart people, g might explain a smaller part of their overall test scores compared to people with lower scores.

For example, studies have shown that for people with very low IQs, g might explain about 75% of the differences in their cognitive test scores. But for people with very high IQs, g might only explain about 30% of the differences. This suggests that at higher levels of intelligence, people's specific abilities might become more distinct from each other.

Why g Matters in Real Life

The g factor is a very strong predictor of success in many areas of life, like school, jobs, and even health. Some researchers believe it's more important than any other psychological factor.

Doing Well in School

The g factor is especially good at predicting how well someone will do in school. This is because g is closely linked to how well you can learn new things and understand ideas.

- In elementary school, g (measured by IQ scores) is strongly connected to grades and achievement test scores.

- In high school, college, and graduate school, the connection is still strong, though it might seem a bit lower because fewer students with lower IQs continue their education.

- About 80% to 90% of what we can predict about school performance comes from g.

Achievement tests (like national exams) are often more connected to g than school grades. This might be because grades can sometimes be influenced by a teacher's personal feelings. For example, in one study, g scores from age 11 were connected to all 25 subjects in a national exam taken at age 16.

The SAT test, used for college admissions, is also largely a measure of g. Studies show a strong connection between g scores and SAT scores.

Getting and Doing Well in Jobs

There's a strong connection between how much prestige a job has and the average g scores of people who work in that job. Jobs with higher prestige tend to have employees with higher average g. This suggests that more complex jobs might require a certain minimum level of g.

Tests of g are also the best single predictors of how well someone will perform in a job. This is true even for simple jobs, but the connection is strongest for complex jobs like professional or scientific roles. It's thought that g helps people learn job-related knowledge faster. So, people with higher g can pick up new skills and information more easily, which helps them do better at work.

Some studies have looked at how g compares to other factors, like emotional intelligence, in predicting job performance. While emotional intelligence can help, especially for people with lower g, general cognitive ability (GCA) still remains the strongest predictor of job performance overall.

Income and Other Life Outcomes

The g factor is also connected to how much money people earn. This connection tends to get stronger as people get older and reach their peak career potential. Even when you consider education, job type, and family background, the connection between g and income doesn't disappear.

Beyond school and work, the g factor is linked to many other life outcomes. For example, people with higher g tend to have fewer social problems, like dropping out of school or having chronic welfare dependency. Higher g in childhood is also linked to better health and longer life in adulthood.

Genes and Environment's Role

The g factor is influenced by both our genes and our environment. Scientists use studies of twins and adopted children to figure out how much each plays a role.

The influence of genes on g (called heritability) is estimated to be between 40% and 80%. This genetic influence tends to increase as people get older. For example, one study found that the heritability of g was 41% at age nine, 55% at age twelve, and 66% at age seventeen. In adulthood, it can be as high as 80%.

However, it's important to remember that heritability applies to a specific group of people at a specific time and place. If an environment has very strong influences (like extreme poverty), the genetic differences might matter less. Also, heritability tells us about differences within a group, not necessarily between groups. It's possible for differences between two groups to be entirely due to environmental factors, even if the trait is highly heritable within each group.

Environmental factors that are unique to each person (like different experiences or friends) also play a big role in developing g, especially in childhood. But the environmental influences that are shared by family members (like growing up in the same house) become less important as people get older.

Scientists have found that the same genes seem to influence many different cognitive abilities. This suggests that when genes for intelligence are found, they will likely be "generalist genes" that affect many different thinking skills.

Brain Science and g

The g factor is connected to many things in the brain. Studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) show that g is moderately connected to the total size of the brain. It's also connected to the size of certain brain areas, like the frontal and parietal parts of the brain.

Most scientists believe that intelligence isn't located in just one part of the brain. Research suggests that the health and efficiency of the brain's "white matter" (which connects different brain regions) are important for intelligence. More intelligent people often use fewer brain resources to do the same task, meaning their brains work more efficiently.

g in Animals

Scientists have also seen evidence of a general intelligence factor in animals, not just humans! Studies have shown that g explains a lot of the differences in cognitive abilities among primates and even mice. While we can't use the same tests as for humans, researchers look at how animals innovate, learn from others, and react to new things. Studying g in animals like mice helps us understand how genes and brain development influence intelligence.

Similarities and Differences Among Groups

Studies across different cultures show that the g factor can be found in almost any group of people taking a variety of complex cognitive tests. The way IQ tests are structured, including the g factor, has been found to be very similar for different sexes and ethnic groups.

Most studies suggest there are very small differences in the average level of g between boys and girls. However, there are often differences in more specific skills: boys tend to do better on spatial tasks, while girls often do better on verbal tasks. Also, boys tend to show more variation in their abilities, meaning there are more boys at both the very low and very high ends of the test score range.

Differences in g between racial and ethnic groups have been observed, especially in the U.S. between Black and White test takers. However, these differences have become much smaller over time and are thought to be due to environmental factors, not genetics. For example, between 1972 and 2002, Black Americans gained several IQ points compared to White Americans.

How g Connects to Other Brain Ideas

Simple Thinking Tasks

Even very simple tasks, called Elementary Cognitive Tasks (ECTs), are strongly connected to g. These tasks seem to require very little intelligence, like quickly deciding if a light is red or blue. The time it takes to react to these simple tasks is strongly connected to g, while the time it takes for physical movement is less connected. ECTs help scientists link traditional IQ tests to brain studies.

Working Memory

Some theories suggest that g is very similar to working memory capacity. Working memory is like your brain's temporary notepad, where you hold information to think about it. Some studies have found that g and working memory are very closely related.

Personality

For a long time, psychologists thought that personality and intelligence were completely separate. Intelligence was about what you can do, while personality was about what you typically do. Studies show that the connections between g and major personality traits (like being outgoing or organized) are generally small. This suggests that g is mainly about thinking skills and is separate from your personality.

However, some researchers argue that these small connections are still important. They suggest that personality traits might affect how well you perform on intelligence tests (e.g., being anxious might lower your score). Another idea is that your personality influences how you use your intelligence, which can help you learn and grow your knowledge.

Creativity

Some scientists believe that you need a certain level of g to be truly creative in a way that impacts society. Below this level, significant creativity is rare. But above this level, personality differences might become more important for creativity.

However, other researchers disagree. They argue that g is still connected to creativity even among very smart people. Studies have shown that people with higher g are more likely to achieve creative successes, like getting patents or publishing books, even within the top 1% of cognitive ability. This suggests that g helps predict how much you achieve, while specific skills predict what kind of creative things you do.

Criticisms of g

Some people have criticized the g factor, especially its historical links.

Past Connections to Problematic Ideas

Research on the g factor has been criticized for its connections to eugenics (a harmful idea about improving humanity through selective breeding) and racialism (the belief that human races have different qualities and abilities). Critics argue that the idea of a single, unchanging g factor was sometimes used to support unscientific theories about race and intelligence.

Some critics have even called the g factor a "pseudoscience," arguing that it's treated as a fact without enough real-world proof.

Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence

Raymond Cattell, a student of Charles Spearman, suggested that g could be split into two main parts:

- Fluid intelligence (Gf): This is your ability to solve new problems and understand new things, even if you've never seen them before. It's like your raw problem-solving power.

- Crystallized intelligence (Gc): This is the knowledge and skills you've gained throughout your life, like your vocabulary or general facts. It's like your accumulated wisdom.

While Gf and Gc are connected, they change differently over time. Gf tends to peak around age 20 and then slowly decline, while Gc stays steady or even increases as you get older. Critics argue that a single g factor doesn't show this difference in how intelligence develops over a lifetime.

However, many researchers, like John B. Carroll, have combined these ideas. Carroll's three-stratum model includes both Gf and Gc, but still places a higher-level g factor at the top, showing how they are all connected.

Ideas About Unconnected Abilities

Some thinkers have proposed that there are different types of intelligence that are completely separate from each other.

- L.L. Thurstone suggested "primary mental abilities" that he thought were independent, but his tests still showed a strong general factor.

- J.P. Guilford proposed a model with up to 180 distinct abilities, but later analyses showed that his own data actually supported the idea of connections between abilities.

More recently, Howard Gardner developed the theory of multiple intelligences. He suggests there are nine different and independent types of intelligence, such as:

- Mathematical intelligence

- Linguistic (language) intelligence

- Spatial (understanding space) intelligence

- Musical intelligence

- Bodily-kinesthetic (movement) intelligence

- And others.

Gardner argues that schools and tests often focus only on language and logic, ignoring other important types of intelligence. While popular in education, many psychologists criticize Gardner's theory. They argue that many of his "independent" intelligences are actually connected to each other. For example, they say that being good at sports or music is usually called a "skill" or "talent," not a separate type of "intelligence."

Robert Sternberg also suggested that intelligence has parts separate from g. He proposed three types:

- Analytic intelligence: What traditional tests measure (like problem-solving).

- Practical intelligence: Your ability to solve real-life problems.

- Creative intelligence: Your ability to come up with new ideas.

Sternberg believes that traditional tests only measure analytic intelligence and that we should also test practical and creative intelligence. He has created tests for these. However, other researchers have argued that even in Sternberg's tests, a single general factor (like g) still explains most of the results.

Images for kids

-

! scope="col"

-

! scope="col"

Classics

-

! scope="col"

French

-

! scope="col"

English

-

! scope="col"

Math

-

! scope="col"

Pitch

-

! scope="col"

Music

-

! scope="row"

Classics

-

! scope="row"

French

-

! scope="row"

English

-

! scope="row"

Math

-

! scope="row"

Pitch discrimination

-

! scope="row"

Music

-

! scope="row"

g

-

! scope="col"

-

! scope="col"

V

-

! scope="col"

S

-

! scope="col"

I

-

! scope="col"

C

-

! scope="col"

PA

-

! scope="col"

BD

-

! scope="col"

A

-

! scope="col"

PC

-

! scope="col"

DSp

-

! scope="col"

OA

-

! scope="col"

DS

-

! scope="row"

V

-

! scope="row"

S

-

! scope="row"

I

-

! scope="row"

C

-

! scope="row"

PA

-

! scope="row"

BD

-

! scope="row"

A

-

! scope="row"

PC

-

! scope="row"

DSp

-

! scope="row"

OA

-

! scope="row"

DS

-

! scope="row"

g

See also

In Spanish: Factor g de inteligencia para niños

In Spanish: Factor g de inteligencia para niños

- Charles Spearman

- Factor analysis in psychometrics

- Fluid and crystallized intelligence

- Flynn effect

- Intelligence

- Intelligence quotient

- Malleability of intelligence

- Spearman's hypothesis

- Eugenics

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |