George Starkey facts for kids

George Starkey (1628–1665) was an American alchemist, a type of early scientist who tried to turn ordinary metals into gold. He was also a doctor and wrote many books about chemistry. His ideas were very important and influenced famous scientists like Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton.

In 1650, Starkey moved from America to London, England. There, he started writing under a secret name: Eirenaeus Philalethes. He continued his work in medicine and alchemy in England until he died in 1665 during the terrible Great Plague of London.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Starkey was born in Bermuda. His father, George Stirk, was a Scottish minister. As a child in Bermuda, Starkey loved nature. He wrote down his observations about insects found there.

After his father died in 1637, Starkey moved to New England. He continued his schooling and then went to Harvard College in 1643 when he was 15. At Harvard, he learned about alchemy. He later called himself the "Philosopher by Fire" because of his interest in chemical experiments.

Starkey graduated from Harvard in 1646. He lived in the Boston area and worked as a doctor. At the same time, he experimented with early chemical technology.

Moving to England

Even though his medical practice was doing well, Starkey moved to London, England, in November 1650. He was 22 years old and had just married Susanna Stoughton. Susanna was likely the daughter of Colonel Israel Stoughton.

It's not fully clear why Starkey left New England. One reason was his passion for alchemy. He was good at building special ovens for his experiments. However, he felt that New England didn't have the best materials for these ovens. He thought England would offer better supplies and tools. Around this time, he also changed his last name to Starkey.

Once in England, Starkey became known as a skilled alchemist and furnace maker. He joined a group of scientists and thinkers called the Hartlib circle. This group included people who wanted to improve society and understand nature.

However, Starkey soon faced money problems. He was put in prison for debt, possibly twice, in 1653 and 1654. After being released, he went back to his work in alchemy and medicine. He also wrote and published several popular books. His most important writings, though, were published after his death. These were written under his secret name, Philalethes.

Learning at Harvard

We don't know much about Starkey's very early schooling. He was probably taught at home before his father died in 1637. After that, he moved to New England around 1639 to continue his studies.

In 1643, he started at Harvard College. There, he studied classical languages, religion, logic, physics, math, and history. He soon focused on chemical philosophy and alchemy. He earned his first degree in 1646 and a master's degree around 1649.

At Harvard, Starkey learned about alchemy through his physics classes. These included topics like how metals might change into other substances. He also gained a strong understanding of how tiny particles make up matter. This was very important for his alchemy work throughout his life.

Career and Discoveries

During his last years at Harvard, Starkey became very interested in practicing medicine. He followed the ideas of a Flemish scientist named Jan Baptist van Helmont, who combined medicine with chemistry. Starkey also learned about how to use metals in practical ways. His medical practice seemed very successful.

Despite his success, Starkey decided England would give him better access to the tools he needed for alchemy. So, he sailed to London with his wife in November 1650.

Becoming Philalethes

When Starkey arrived in London, he quickly became known as a brilliant alchemist. This was partly because of his connections with other scientists from New England. It was then that he joined the Hartlib circle. This group helped create his secret identity, Eirenaeus Philalethes, which means "a peaceful lover of truth."

Samuel Hartlib supported applied science, including alchemy and medical chemistry. But some people in the group wanted to keep their knowledge secret. This might have inspired Starkey to use a hidden identity.

Starkey's move to London was followed by great success in his medical practice. He created and gave medicines to many patients, including Robert Boyle. However, in 1651, Starkey left his patients to focus on the "secrets" of alchemy. This included making medicines and trying to change metals.

For example, Starkey's "sophic mercury" was a mix of antimony, silver, and mercury. He believed it could dissolve gold into a special mixture. When heated, this mixture was supposed to create the mythical philosopher's stone. This stone was thought to turn common metals into valuable ones like gold. Starkey also taught Boyle about chemistry and experiments, though Boyle never publicly said so.

Protecting His Secrets

As the creator of new medicines and chemical substances, Starkey wanted to protect his inventions. The name "Philalethes" helped him do this. He wrote many papers under this secret name, announcing his discoveries. He also hinted that hidden alchemical knowledge could be found through Starkey, who was a "friend" of Philalethes and guarded his writings.

It's also thought that Starkey wanted to hide his work to make himself seem like a "master of secrets." He wanted people to believe his discoveries were "divinely inspired." This would help him gain respect and support from important people in the Hartlib circle.

Challenges and Later Life

A few years after arriving in London, Starkey started to struggle. He was working on many different projects, from perfumes and medicines to his sophic mercuries. This pulled him in too many directions and caused problems with his colleagues. These projects also didn't earn enough money. He was spending a lot of his own money, and his debts grew.

Finally, in 1653–1654, Starkey's creditors caught up to him. He was imprisoned twice for debt. When he wasn't in prison, he hid to avoid those he owed money to. To make things worse, he lost the support of the Hartlib circle. Starkey desperately needed to get his finances back on track, fix his reputation, and find new supporters.

In his final years, Starkey focused on rebuilding his medical practice and making medicines that would earn him money. But he never stopped working in his chemistry lab. He continued his search for alchahest, a universal solvent, and the philosopher's stone. He hoped to find the perfect alchahest, a medicinal liquid similar to theriac, which was used to stay healthy and prevent illness.

Starkey had limited success with his alchahest, and he never found the philosopher's stone. He kept writing medical books. However, three political pamphlets he wrote in 1660, along with public arguments with other doctors, further damaged his career.

In 1665, the plague reached London, and George Starkey caught it. He believed his Helmontian medicines could cure diseases and prevent illness. But the alchahest he prepared to fight the plague was not effective. Starkey remained loyal to the Flemish medical chemist he admired until the very end.

Legacy and Influence

George Starkey was highly respected for his skills in the alchemy lab and his organized way of doing experiments. His methods became important for later chemistry practices in the 1700s. His influence on Robert Boyle's work and discoveries in chemistry is very clear.

Perhaps most importantly, Starkey's laboratory journals survived. These journals give us a rare look into how an alchemist worked in the 1600s. Also, Starkey's written works, especially those under the name Philalethes, were very popular and read by many important scientists. These included Boyle, Locke, Leibniz, and Newton.

His writings helped develop the new field of chemistry. They promoted the idea that chemical events happen because tiny, unseen particles interact with each other. While George Starkey might not be as famous as some other scientists from his time, his achievements are still very important. They help us understand how science developed during that period.

Original Published Works

Works published under George Starkey's name:

- The Reformed Commonwealth of Bees (1655).

- Nature's Explication and Helmont's Vindication; or a short and sure Way to a long and sound life (London, 1657).

- Pyrotechny asserted and illustrated (London, 1658).

- The admirable efficacy of oyl which is made of Sulphur-Vive (1660).

- The dignity of kinship asserted (1660).

- Britains Triumph FOR HER Imparallel'd Deliverance (1660).

- Royal and other innocent blood crying aloud to heaven for due vengeance (1660).

- An appendix to the Unlearned Alchimist Wherein is contained the true Receipt of that Excellent Diaphoretick and Diuretick PILL (1663).

- George Starkey's Pill vindicated From the unlearned Alchymist and all other pretenders, (undated).

- A brief Examination and Censure OF Several Medicines (1664).

- A smart Scourge for a silly, sawcy Fool, an answer to letter at the end of a pamphlet of Lionel Lockyer (1664).

- An Epistolar discourse to the Learned and Deservingauthor of Galeno-pale (1665).

- Loimologia A Consolatory Advice And some brief observations Concerning the Present Pest, 1665.

- Liquor Alchahest, or a discourse of that Immortal Dissolvent of Paracelsus & Helmont, 1675.

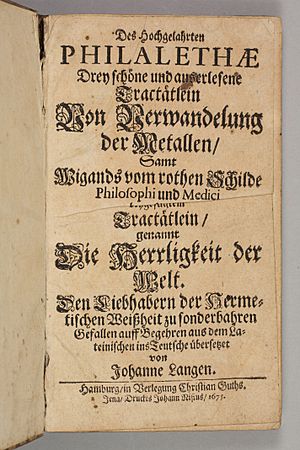

Works published under the name of Philalethes.

First printings of Philalethes' writings were published between 1654 and 1683:

- (in la) Introitus apertus ad occlusum regis palatium. Amstelodami: J. Janssonium. 1667. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k746977.

- Later translated as:

- Three Tracts of the Great Medicine of Philosophers for Humane and Metalline Bodies (Amsterdam, 1668, in Latin; London, 1694, in English)

- The Art of the Transmutation of Metals

- A short Manuduction to the Caelestial Ruby

- The Fountain of Chymical Philosophy

- An Exposition upon Sir George Ripley's Epistle to King Edward IV (London 1677, in English)

- An Exposition upon Sir George Ripley's Preface (London 1677, in English)

- An Exposition upon the First Six Gates of Sir George Ripley's Compound of Alchymie (London 1677, in English)

- Experiments for the Preparation of the Sophick Mercury; by Luna, and the Antimonial-Stellate-Regulus of Mars, for the Philosophers Stone (London 1677, in English)

- A breviary of Alchemy, or a commentary upon Sir George Ripley's Recapitulation: Being A Paraphrastical Epitome of his Twelve Gates (London 1677, in English)

- An Exposition upon Sir George Ripley's Vision (London 1677, in English)

- Ripley Reviv'd, or an Exposition upon Sir George Ripley's Hermetico-Poetical Works (London 1678, in English)

- Opus tripartitum (London&Amsterdam, 1678, in Latin)

- Enarratio methodica trium Gebri medicinarum, in quibus contenitur Lapidis Philosophici vera confectio (Amsterdam, 1678, Latin)

- The Secret of the Immortal Liquor called Alkahest (London, 1683, English & Latin)

Many of these writings, including the Three tracts and the Introitus, were also included in the Musaeum Hermeticum of 1678.

All English works by Philalethes have recently been collected into one book.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |