German Reformed Sanctity Church Parsonage facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

German Reformed Sanctity Church Parsonage

|

|

South (front) facade, 2013

|

|

| Location | Germantown, New York |

|---|---|

| Area | 1.3 acres (5,300 m2) |

| Built | c. 1746 |

| NRHP reference No. | 76001209 |

| Added to NRHP | January 30, 1976 |

The German Reformed Sanctity Church Parsonage, also known as the First Reformed Church Parsonage, is a very old house in Germantown, United States. It was built around the mid-1700s. This makes it the oldest building in the town of Germantown.

The house is made of wood, brick, and stone. In 1976, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. This list includes important historical buildings across the country.

When the parsonage was built, the area was called East Camp. Many German Palatine people lived there. These were refugees who had come to England and then moved to the Hudson Valley. They were part of a plan to make supplies for ships. The church was started soon after these first Palatines arrived. The parsonage was built in the 1740s and made bigger about 20 years later.

The church sold the house in the early 1800s. Pastors still lived there for about 25 more years. For most of the 1800s and 1900s, different local families lived in the house. By the 1940s, the house needed a lot of work. It was updated with modern things like electricity and plumbing.

Today, the town of Germantown owns the parsonage. It is now home to the town's history department. An archaeological dig happened nearby. A professor from Bard College led the dig. Many old items were found, and some are now on display inside the house. You can find more information about the dig online at the Germantown Exhibits portal.

Contents

Exploring the Parsonage Building

The parsonage sits on a 1.3-acre (5,300 m2) piece of land. It is on the north side of Maple Avenue in central Germantown. The area around it feels like the countryside. There are farms to the west and other houses nearby. To the north is a large forest. A smaller forest to the south is next to baseball fields. The land gently slopes down towards the Hudson River, which is about half a mile away.

In front of the house, there is a low stone wall. This wall is a memorial to the first settlers. There is also a modern sign that tells about the history of the place.

How the House Looks

The parsonage is a one-and-a-half-story building. It has two main parts. One part is made of fieldstone, and the other is made of wood. Both parts have roofs that slope down on the sides. Brick chimneys stick out of the roof at each end. The house is built on a slope, so you can see the basement on the east side.

The walls of the eastern part are very thick, about three feet (1 meter). They are made of stone blocks covered with stucco. The western part is made of wood with bricks inside the walls. It is covered with asbestos shingles on the outside. All the windows are set back into the walls. They have two sashes that slide up and down.

Windows and Doors

The windows look different depending on where they are. In the basement, there are two windows with eight small panes of glass on the top and eight on the bottom. On the first floor, the windows have 12 panes on the top and 12 on the bottom. They have a small decorative arch above them. The east part of the house has two modern storm windows. There is also a small window that opens outwards, just below the roof.

The sides of the house do not have windows on the basement or first floor. At the back, there are two doors. One leads to the kitchen, and the other to the cellar. The roof is very steep and covered with slate shingles.

The main front door is a modern glass door in front of an older wooden door. This door opens into a central hallway. There are two rooms to the east and one to the west. The floors throughout the house are made of wide pine planks. Many rooms still have their original pine woodwork. The cellar is different, with its original pressed clay floor. It also has a large fireplace with an oven. Upstairs, the attic is divided into three small rooms with a hallway in the middle.

Archaeological Discoveries

Between 2010 and 2014, students from Bard Archaeology's Field School worked at the parsonage. Dr. Christopher Lindner led the project. They dug up an old well from the 1700s. They rebuilt the outer wall of the well using rocks that had filled it up. The well was hidden under a thick layer of earth on the lawn. You can see pictures of their work online at Bard College's Archeology site.

A Look Back: History of the Parsonage

In 1709, many refugees from Germany came to England. They were fleeing the War of the Spanish Succession. These people became known as Palatines. The British government decided to move them to the upper Hudson Valley in America. The plan was for them to collect pine tar for the British Navy. This tar was used to make ships. Their presence also helped protect the northern border of Province of New York from the French.

Early Settlement and Church Life

The plan to make tar did not work out. So, after 1711, some Palatines moved to other parts of New York. The 63 Palatine families in the "East Camp" area found the land similar to their home in Germany. They started farms. By 1726, they officially owned these lands.

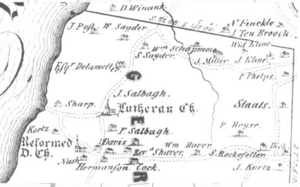

The German Reformed Sanctity Church was started by the Palatines soon after they settled. By the 1720s, a church building was built nearby. Records show the church owned the land for the parsonage by 1741. The parsonage was likely built by 1746. That's when Casper Ludwig Schnoor became the church's first pastor to live there.

At first, the building was only its current western part. The main entrance was where a cellar window is now. It's also possible that the second story and attic were added later. The house looks similar to other buildings made by Palatines around the same time.

Changes Over the Years

Johannes Casparus Rubel became the pastor in 1751. He stayed longer than the first pastor. The parsonage was made bigger in 1767 when the eastern part was built. In 1805, the church sold the building to Maria Delamater. Pastors continued to live there until 1829. Then, a local doctor named Wessel Ten Broeck Van Orden bought it.

Van Orden lived in the house for 20 years. After him, several local families owned the house. Many of these families were African American. By 1944, the house was very old and needed a lot of repairs. The Ekert family bought it that year.

The Ekerts started a big restoration project. They focused on fixing the house's structure. New wooden beams were used to replace old ones. Steel beams were added above windows for support. Rotten floor joists were also fixed with steel. The chimneys were repaired. The cellar door on the front was changed into a window for safety. Inside, the kitchen was updated. Electricity, modern plumbing, and heating systems were added. These changes were made carefully to keep the house's historic look.

In 1990, the Ekerts gave the house to the town. The town has used it as the office for its historian. In the late 2000s, Christopher Lindner, an archaeologist from Bard College, started leading digs near the parsonage. They found pieces of old pottery, including china. These items date back to the early years of the parsonage. They suggest that the pastors lived like wealthy people. Some of these items are now on display in the house. The house is open to visitors on Saturdays. There is also evidence that another building once stood in the yard to the west.

See also