Greater London Council leadership of Ken Livingstone facts for kids

Ken Livingstone was a British politician from the Labour Party. He became the leader of the Greater London Council (GLC) on 17 May 1981. He stayed in this important role until the GLC was closed down on 1 April 1986. During his time, he brought in many new and sometimes controversial ideas for how London should be run.

Contents

Ken Livingstone and the GLC: A New Start

Becoming a Leader

Ken Livingstone wanted to change how the GLC worked. In 1979, he started a newsletter called London Labour Briefing. He encouraged people who shared his socialist ideas to become candidates in the upcoming GLC election.

In May 1981, Livingstone won his seat in Paddington. He supported other Labour candidates across London. Some people, like Conservative leader Horace Cutler, worried that a Labour victory would mean "Marxists and extremists" taking over London. Newspapers like the Daily Express also wrote scary headlines.

Despite these worries, Labour won the GLC election on 6 May 1981. Andrew McIntosh was first made the leader. But within 24 hours, Livingstone and his supporters changed this.

Taking Charge of County Hall

On 7 May, Livingstone gathered his supporters. He announced he would challenge McIntosh for the leadership. In a vote, Livingstone won by 30 votes to 20. This meant he was the new leader of the GLC. His team also took control of the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA).

Some people, including McIntosh, said this change was not fair. Many newspapers criticized Livingstone. The Daily Mail called him a "left wing extremist." The Sun gave him the nickname "Red Ken." Even Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said that people like Livingstone did not respect democracy.

Leading London: 1981-1983

Facing the Media Spotlight

When Livingstone became GLC leader on 8 May 1981, he made immediate changes at County Hall. He made the building more open to the public, allowing citizens to hold meetings there for free. County Hall became known as "the People's Palace." He also removed some special benefits for GLC members, like chauffeurs and free alcohol.

Livingstone believed his team was the real opposition to Margaret Thatcher's government. The media often focused on him, usually in a negative way. The Sun newspaper tried to find bad stories about him but couldn't. They instead made fun of his love for amphibians. One magazine even spread false rumors about him, but later apologized and paid him money.

New Faces and New Plans

In 1982, Livingstone brought new people into key roles at the GLC. John McDonnell became the finance chair. Valerie Wise led the new Women's Committee. These changes helped create a more stable environment for the GLC.

Livingstone also tried to become a Member of Parliament for Brent East. He had many friends there and felt a connection to the area. However, he missed the deadline to apply. Even so, many local Labour members would have voted for him. In 1983, Livingstone also started co-hosting a TV chat show.

Fair Fares for Londoners

One of the main promises of the 1981 Labour manifesto was called Fares Fair. This plan aimed to cut London Underground fares and keep them low. The idea was to encourage more Londoners to use public transport and reduce traffic. In October 1981, the GLC cut fares by 32%. They planned to pay for this by increasing local taxes.

However, the legality of Fares Fair was challenged by the Bromley council. They argued that their residents had to pay for cheaper fares even though the Underground did not run in their area. After several court cases, the House of Lords ruled that the Fares Fair policy was illegal in December 1981. They said the GLC could not run London Transport at a loss.

Livingstone wanted to ignore the court's decision, but his team voted against it. Instead, they started a campaign called "Keep Fares Fair" to change the law. While the original plan failed, a new system of flat fares within ticket zones and the Travelcard ticket were kept. In January 1983, the GLC successfully introduced a smaller fare cut of 25%, which was ruled legal.

Supporting London's Economy

Livingstone and Mike Cooley created the Greater London Enterprise Board (GLEB). GLEB aimed to create jobs by investing in London's industries. The council and its pension fund provided money for this. However, some of GLEB's goals were difficult to achieve due to opposition.

The GLC also tried to stop the sale of council housing, but this largely failed because of strong opposition from the Conservative government. The ILEA also tried to cut the price of school meals, but legal advice forced them to stop.

London as a Nuclear-Free Zone

Livingstone's administration took a strong stand against nuclear disarmament. On 20 May 1981, the GLC stopped spending money on nuclear war defense plans. They declared London a "nuclear-free zone." They even published the names of politicians and administrators who were planned to survive in bunkers during a nuclear attack. Margaret Thatcher's government strongly disagreed with these actions.

Helping Diverse Communities

As a socialist, Livingstone's government wanted to improve the lives of minority groups in London. These included women, disabled people, homosexuals, and ethnic minorities. Together, these groups made up a large part of London's population. The GLC greatly increased its funding for voluntary organizations that helped these groups.

In July 1981, Livingstone created the Ethnic Minorities Committee, the Police Committee, and the Gay and Lesbian Working Party. A Women's Committee was added in June 1982. He believed the Metropolitan Police were unfair to some groups.

Conservatives and the media often criticized these policies. They called them "loony left" and said they only helped "fringe" interests. Some journalists even made up stories to make Livingstone and his policies look bad. For example, they falsely claimed the GLC made workers drink only Nicaraguan coffee. Despite the criticisms, many people now believe that the GLC's work helped change social attitudes towards women and minorities in London.

The End of the GLC: 1983-1986

Why the GLC Was Abolished

The 1983 general election was very bad for the Labour Party. Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government won a second term. The Conservative government believed the GLC wasted taxpayers' money. They wanted to abolish it and give control to London's local boroughs. They stated this plan in their 1983 election promises.

Norman Tebbit, a government minister, called the GLC "Labour-dominated, high-spending and at odds with the government's view." Livingstone agreed there was a "huge gulf" between the GLC's values and Thatcher's. The government felt confident they could abolish the GLC because many Londoners were unhappy with Livingstone. A poll in April 1983 showed that 58% of Londoners were dissatisfied with him.

Fighting to Save the Council

The GLC fought hard against the plans to abolish it. They spent £11 million on a campaign that included advertising and talking to Members of Parliament. Livingstone traveled around, convincing other parties like the Liberals and Social Democrats to oppose the abolition.

The GLC used the slogan "say no to no say." They pointed out that if the GLC was abolished, London would be the only capital city in Western Europe without a directly elected local government. The campaign was successful, and polls showed that most Londoners wanted to keep the Council. On 29 March 1984, 20,000 public workers went on strike to support the GLC.

Despite this, the government remained determined. The bill to abolish the GLC had to pass through Parliament. On 28 June 1984, the Local Government Act 1985 was passed. The GLC was officially closed down at midnight on 31 March 1986.

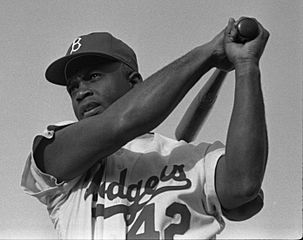

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |